The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Chapter 1:

Chapter 2:

Chapter 3:

Chapter 4:

Chapter 5:

Chapter 6:

Chapter 7:

Chapter 8:

Chapter 9:

In memory of Adam Johnson

19651993

You great composer, I little composer.

D MITRI S HOSTAKOVICH

I want to say, here and now, that Britten has been for me the most purely musical person I have ever met and I have ever known.

S IR M ICHAEL T IPPETT

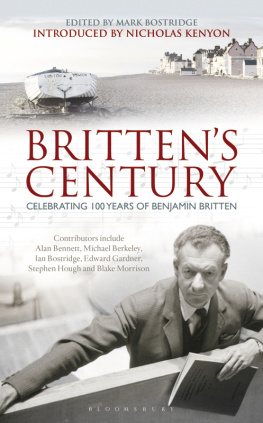

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

In writing this book, Ive proceeded from assumptions which may not be universally shared but which I hope will be vindicated in the following pages. The first is that Benjamin Britten was the greatest of English composersrivalled only by Henry Purcell and Edward Elgarand one of the most extraordinarily gifted musicians ever to have been born in this country: these are slightly different things, of which the latter is perhaps the more clearly incontrovertible, and they certainly dont suggest that he was infallible. The second is that he was specifically a man of the East Anglian coast, which is inclined to foster (as those of us who have lived by it know) a particular cast of mind, in whose life and work we should expect to discover kinships with Suffolk artists and poets such as Constable and Crabbe. The third is that his fondness for adolescent boys and his devotion to his partner, Peter Pears, represent distinct and complementary aspects of his sexual nature; his conduct in both cases was exemplary and is therefore the occasion for neither prurience nor evasiveness. And the fourth is that in two phases of his careerthe periods of his involvement with the Auden Generation in the 1930s and of his formative work with the Aldeburgh Festival from 1948 onwardshe contributed to cultural life in ways which go beyond those to be expected of any composer and performer, however great.

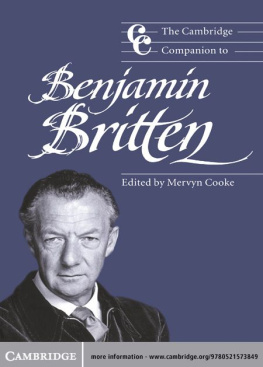

This is not a book by a musician, by which I mean that although I can struggle with a score I dont read it fluently nor do I hear it accurately in my head; if I take the score to the piano, a further lengthy struggle ensues, from which I usually retire in defeat. For people such as myself, notated music examples in biographies are a form of reproachful torment, so I havent included any. I write about music as I hear and understand it, in very much the same way as Ive written about poems and novels in books about authors: the reader who is used to literary biographies will, I hope, feel perfectly at home here. And because I approach Brittens work from this direction, Ive been particularly interested in the relationship between his music and its literary sources, in some of his song settings and in operas such as Peter Grimes , Billy Budd , The Turn of the Screw and Death in Venice . For the musicologist, there are other studies of Britten by people whose scholarly and technical expertise astonishes me and to whom (as the Bibliography and Notes will testify) I remain greatly indebted.

Both the Britten Estate and the BrittenPears Foundation kindly gave their approval to this project at the outset, although they obviously bear no responsibility for the finished book. My agent, Natasha Fairweather, has been an unfailing source of encouragement and support, while Sarah Rigby, my editor at Hutchinson, read and annotated my draft text with exemplary care: Ive acted on far more of her suggestions than is habitual for an obstinate author and its been a pleasure to work with her. Im also deeply grateful to the following people, whom Ive listed in alphabetically democratic style, for their help and advice at various stages of my work on Britten: John Amis, Amanda Arnold, Alan Britten, Nick Clark, Paul Driver, Roger Eno, Maurice Feldman, Caroline Gascoigne, Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, John Greening, Jocasta Hamilton, Rex Harley, Ray Herring, David and Mary Osborn, Philip Reed, Jonathan Reekie, Peter Scupham, Margaret Steward, David Stoll, Malcolm Walker, Martin Wright. Extracts from the letters and diaries of Benjamin Britten and from the travel diaries of Peter Pears are The Trustees of the BrittenPears Foundation and are not to be further reproduced without prior permission.

The best of all companions to the music of Britten, whether in the concert hall or on record, was my friend Adam Johnson. I have constantly wished that I could try out ideas and phrases on him while writing this book, which he would certainly have improved. It is dedicated, with love, to his memory.

N. P.

Orford, 2012

CHAPTER 1

BRITTEN MINOR

191330

The Suffolk coastal resort of Lowestoft, where Benjamin Britten was born in 1913, was described in the mid-nineteenth century as a handsome and improving market town , bathing-place , and sea port which, when viewed from the sea, has the most picturesque and beautiful appearance of any town on the eastern coast. This was just before the arrival of the railway in 1847 and the massive development of South Lowestoft, between Lake Lothing and the previously separate villages of Kirkley and Pakefield, by Sir Morton Peto of Somerleyton Hall. Thirty years later, Anthony Trollope would choose Lowestoft as the setting for a pivotal chapter in his novel The Way We Live Now , transporting three characters Paul Montague, Winifred Hurtle and Roger Carbury to the town: Paul rashly meets Mrs Hurtle there and bumps into Roger, who has been his rival for the hand of another woman. At that time, South Lowestofts principal building was the Royal Hotel of 1849: though unnamed by Trollope, it is evidently the scene of Paul Montague and Winifred Hurtles meeting. In one filmed version of The Way We Live Now , part of the episode takes place on a hotel balcony, from which the former lovers watch the sun set over the sea; but this is something they couldnt have done in Lowestoft, since it is the most easterly point on the English coastline, although on a clear morning you might see the sun rise. What is just as likely to greet you, if you look out from the Victorian houses of Kirkley Cliff Road, across the slender green space of the bowls club towards the beach and sea, is an easterly onshore breeze and sleet in the wind.

During the early years of the last century, one of these houses, 21 Kirkley Cliff Road, was occupied by a dentist, Robert Victor Britten, his wife Edith Rhoda (ne Hockey) and their family. A semi-detached villa with its entrance lobby to the left-hand side, it was to contain a dental practice for most of the twentieth century and is now a small hotel called Britten House; opposite, next to the bowling green, theres a car park adorned with aluminium seats and cycle racks, flying-saucer lamp posts and a few municipal saplings in little gravelled squares. Robert Britten, whose father ended up running a dairy business in Maidenhead, where he died in 1881, had originally hoped to be a farmer, but this ambition was thwarted by his lack of the necessary capital. Instead, he trained at Charing Cross Hospital before working as an assistant dentist in Ipswich and, in 1905, setting up his own practice at 46 Marine Parade, Lowestoft; three years later, his growing family and increasing prosperity prompted him to move the mile further south to Kirkley Cliff Road. There, every day at eleven oclock, he would habitually leave his ground-floor surgery for a fortifying mid-morning whisky, ascending to the first-floor sitting room which he called Heaven; downstairs, he seems to have implied, was the other place. Theres a hint in this habit of that continuous rumbling dissatisfaction, not unlike toothache, with which Graham Greene so memorably burdened his dentist, Mr Tench, in The Power and the Glory . Yet, probably because he didnt relish his profession, Robert Brittens patients found him sympathetic and friendly; he was able to share and respond to their feelings to a greater extent than a more enthusiastic practitioner of his craft might have done.