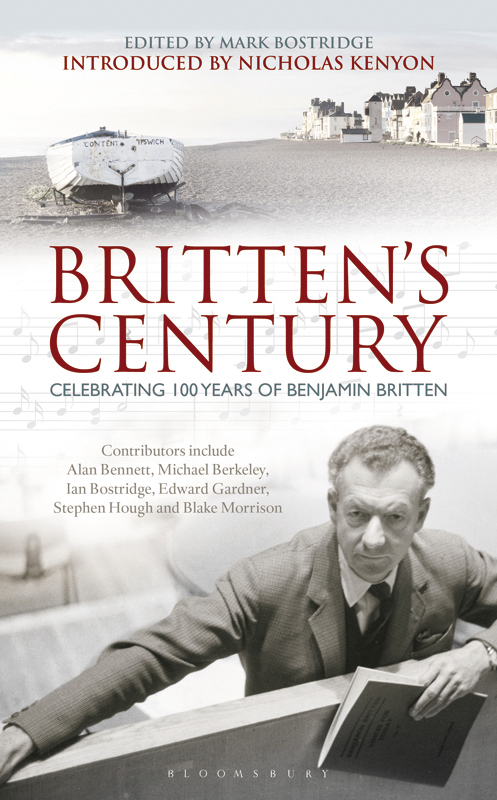

Brittens Century

Celebrating 100 Years of

Benjamin Britten

Edited by

Mark Bostridge

Introduced by

Nicholas Kenyon

First published in Great Britain 2013

This collection and editorial material copyright Mark Bostridge, 2013

Copyright in individual chapters is held by the contributors.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the Publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the Publishers would be glad to hear from them.

A Continuum book

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4411-5186-5

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

Contents

My thanks to the Britten-Pears Foundation for their support of this project. In particular, Id like to express my gratitude to Richard Jarman, the Foundations General Director, and to Ghislaine Kenyon, one of its trustees, for all their kind assistance.

Information concerning the worldwide celebrations of the Centenary of Brittens birth in 2013 may be found on the Foundations website: www.britten100.org/home.

At Bloomsbury, thanks are due to Nicola Rusk, Joel Simons and Robin Baird-Smith.

M. A. B.

I never knew Benjamin Britten. I never met him, I never saw him conduct or perform live. Yes, I sang his music, and loved it; yes, I heard his music, and marvelled, but I had no contact at all with him as a person. This would be supremely unimportant, were it not for the turmoil of claimed closeness and controversial relationships (or non-relationships) which lie at the heart of so much testimony about him. Britten is one of those supreme creative figures who exert a quasi-magical personal attraction: as Michael Tippett said when he died, I think that all of us who were close to Ben had for him something dangerously close to love. Through all the elements of his life his writings, his interviews, his conducting, his car-driving, his walking on the beach, his festival planning and his piano-playing you sense a magnetic personality which affected all those who came into contact with him. As a result, throughout his life and after, people have wanted to own him. Colin Matthews recalls how so many recollections of Britten are burnished through being repeated constantly over time which may be the fate of any great figure, but this goes further. In another context (writing about Mozart) Maynard Solomon has described biography as a contest for possession, and how true that is in the case of Britten. There is something equally Mozartian in the way we feel we can touch Britten the man through the vividness of his communication, both musical and verbal; but how much was deliberately unrevealed, and in the end repressed?

As Paul Kildeas opening chapter vividly describes, reflecting on the biographies that have preceded his own, Brittens reputation has been continuously contested by his executors, his corpses, his colleagues, his performers, by modernists and anti-modernists, and more recently by gay studies. It is entirely natural that those who felt most touched and transformed by contact with the composer should argue the case for their view of him. But a century after his birth, we perhaps need to stand back. This book assembles a collection of testimonies, ranging from those who worked most closely with Britten to those who in a newer generation are reacting to his music, and those who offer new perspectives on his work. Together they offer a certainly partial but hopefully stimulating perspective on the creative years of Brittens century.

When, at the BBC Proms in 1997, we invited Philip Brett to give a broadcast lecture as part of a Britten weekend (or as he put it, typically apologizing for being too establishment, appearing under the auspices of the Proms Lecture funded by the BBC) it was already over two decades into his ground-breaking writing on the influence of Brittens sexuality on his work. He had started from where Hans Keller had begun, in showing the impact of Brittens homosexuality on Peter Grimes (an enormous creative advantage, Keller had called it), but developing this thought to articulate a much broader concept of Brittens difference. Though the influence of Brittens sexuality had been widely debated in the decades after his death, the line of argument that Brett advanced was not even by then a comfortable one for some who believed that Brittens homosexuality was essentially peripheral to his artistic achievement. Brett argued that it was central, and shortly after, his view of Britten was accepted into the citadel of recognized musicology, Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians, in the form of a new entry on the composer. That fine article (oddly marred by a gender misprint in its opening section!) should have led, as Kildea explains, to a new full-length biography that was cut short by Bretts own untimely death.

A key figure in maintaining and interpreting the reputation of Britten after his death has been his executor, chronicler, publisher and friend Donald Mitchell. In retrospect it seems entirely right and generous that, as the single person to whom we owe most for our detailed knowledge of and understanding of Brittens life, Mitchell in the end backed away from the prospect of writing a full biography of the composer. He embraced and promoted the most comprehensive documentation, but in spite of Brittens request to him, left an overall re-interpretation to others. Mitchell initially reacted strongly against Humphrey Carpenters freshly re-thought and lively biography (1992), which, as Kildea points out, used a second-hand report of an early traumatic incident as the basis on which to construct an entire theory of Brittens personality. Brett tried to point out (in a review of the earlier volumes of Britten letters) that Mitchell, who has a great deal invested in Brittens stature, should see the question of Brittens homosexuality not as primarily a sexual issue but as an issue with broader cultural and societal implications. This was a key to understanding the composer, which led us to the heart of one issue which recurs through this book of essays: was Britten an insider or an outsider? Did he consider himself to be one or the other, yearning to be accepted into the middle classes while retaining a lifestyle that was reviled by many of that class, or maintaining an external pose while accepting the trappings of the establishment? Did he attempt to influence or construct his identity, or did he simply create his music and let others decide?

Bretts seminal lecture, reprinted here in the spoken form in which he gave it, and his subsequent Grove article, contain one of the most thought-provoking sentences that has been written about the composer, expressed with typically concise eloquence: Brittens artistic effort was an attempt to disrupt the centre that it occupied with the marginality it expressed. This is certainly not a formulation that the composer would have recognised, with his repeated claims to be of use to people, to serve the community. It is quite a good thing to please people, he said, and thus proposed a rather cosier view of his place in society. The broad concept of difference is one that Brett articulated in his other primary area of study, that of early music. He wrote a generation ago that the historical performance movement has given us a sense of difference, a sense that by exercising our imaginations we may, instead of reinforcing our own sense of ourselves by assimilating works unthinkingly to our mode of performing and perceiving, learn to know what something different might mean and how we might ultimately delight in it. That has a very close resonance with the story of Britten, because what has happened since it was written is that Brittens music (just like the performance practices of the early music movement), having started as a resolutely non-central, critical feature of our musical life, has actually become central to it. As a result, in both areas, the centre has moved.