Contents

Guide

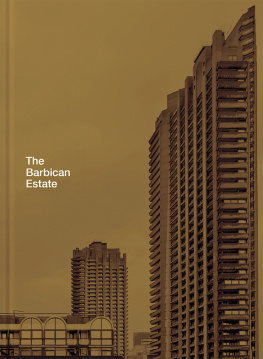

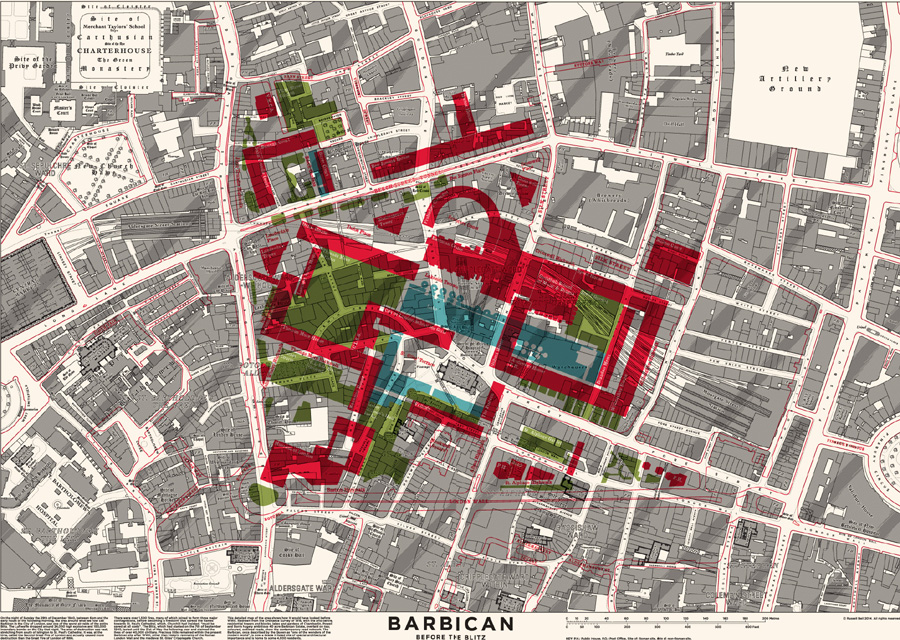

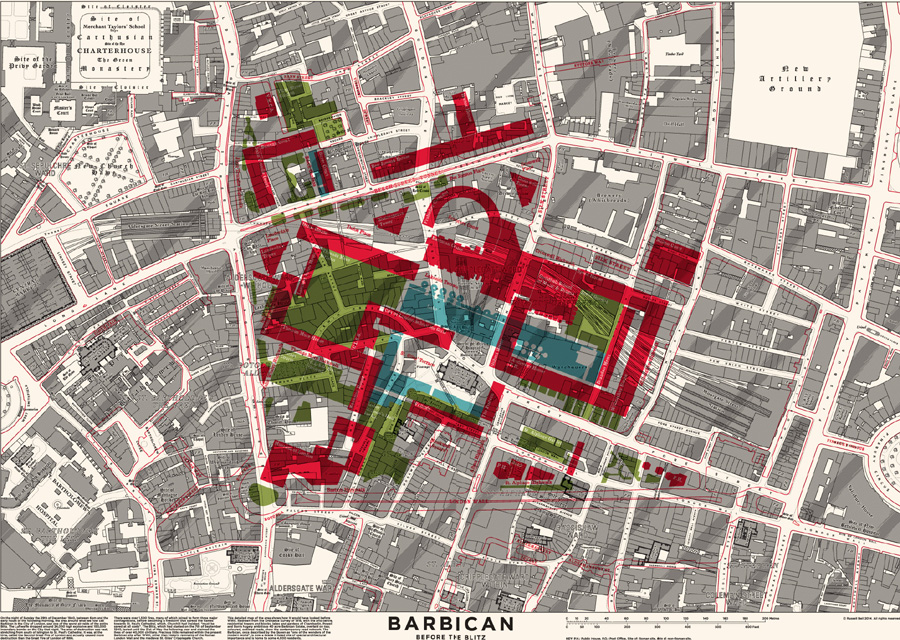

Illustration by Russell Bell, 2014. This shows the Barbican development superimposed in colour on the Ordnance Survey map of the area before the Blitz of 1940/41. In the centre of the picture is the surviving church of St Giles Cripplegate, which provides the alignment for the whole estate. On the left is the semicircular shape of Jewin Crescent, echoed in the Barbicans new Frobisher Crescent.

Contents

Nicholas Kenyon

Fiona Shaw

Robert Hewison

Nicholas Kenyon

Elain Harwood

Roma Agrawal

Philip Dodd

Fiona Maddocks

Lyn Gardner

Philip Dodd

Theo Inglis

Tony Chambers

Sukhdev Sandhu

Philip Dodd

Preface

Nicholas Kenyon

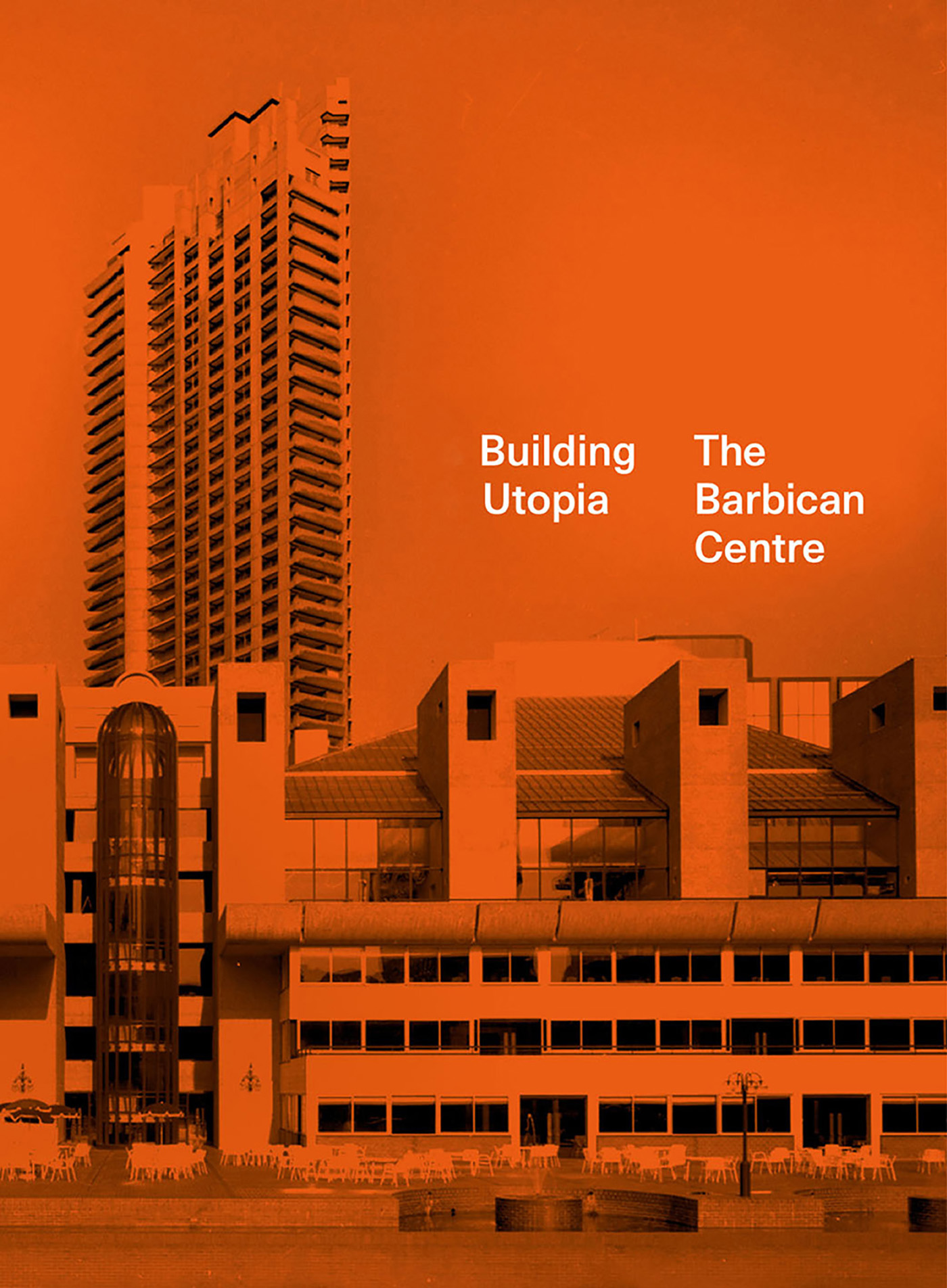

There are many stories told about those who have lived the unique project that is the Barbican Centre: those who designed and re-designed it in its daunting scale and complexity; those who battled to construct it, often under dreadful conditions; those who argued for (and against) its large and seemingly ever-expanding funding; those who have created its vibrant artistic and dynamic commercial programme; those who have welcomed and guided audiences and visitors; and those who have worked constantly to maintain and enhance the building. Some have hated it, some have loved it, but millions have made use of the Barbican over four decades of near-continuous activity, and have come to value its profound contribution to civic and urban life.

We have sought to provide perspectives on why and how the Barbican was created, to give critics and writers free rein to assess the centres programme across the years, and to provide a rich visual impression of this unique building, including much rare archive material. We do not tell a strictly chronological story, so there are repetitions and cross-references: there are accounts of the background by Robert Hewison, Elain Harwood and myself; conversations curated by Philip Dodd with those who have guided the organisation; studies of the art-forms by Fiona Maddocks, Lyn Gardner, Tony Chambers and Sukhdev Sandhu, which are interspersed with first-hand comments from some of those involved, from the plant room at the base of the building to the conservatory at the top. Roma Agrawal writes about the key building material, concrete; Theo Inglis considers the changing visual aspects of the distinctive brand.

We have not sought to impose any view, leaving authors free to make their own choices and to express their opinions. We cannot possibly cover everything that has happened; our chronology is a selective list of highlights. We take the story through the enforced closure of 2020, up to the re-opening in May 2021, to provide a context for the 40th anniversary in March 2022. The sheer diversity of the work and the contrasted approaches to the concept of an arts centre provide many different perspectives across the years, but through it all there shines one shared conviction: that any humane vision of the future must have the arts at its heartthat, if ever, is how we will build utopia.

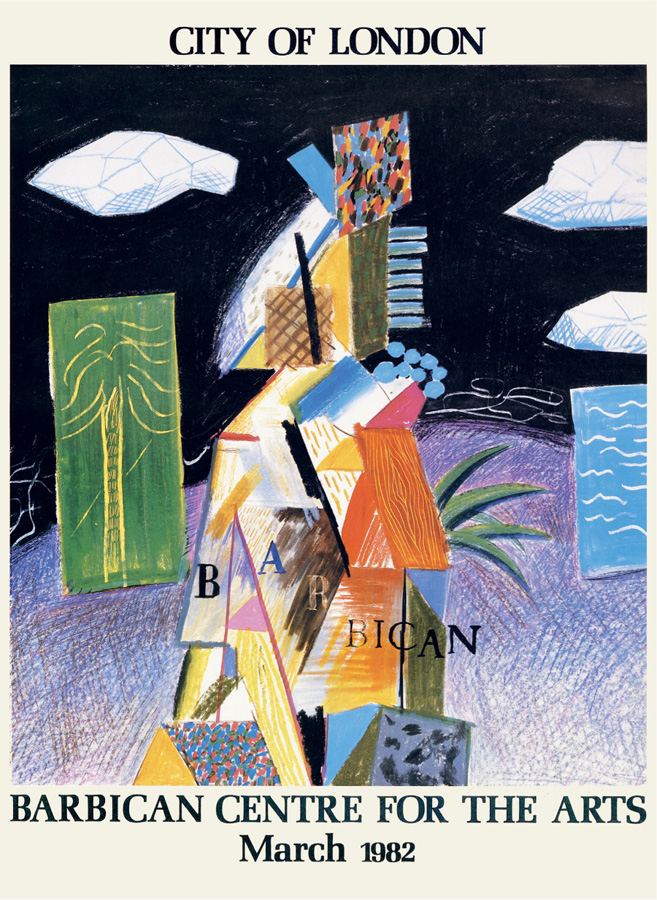

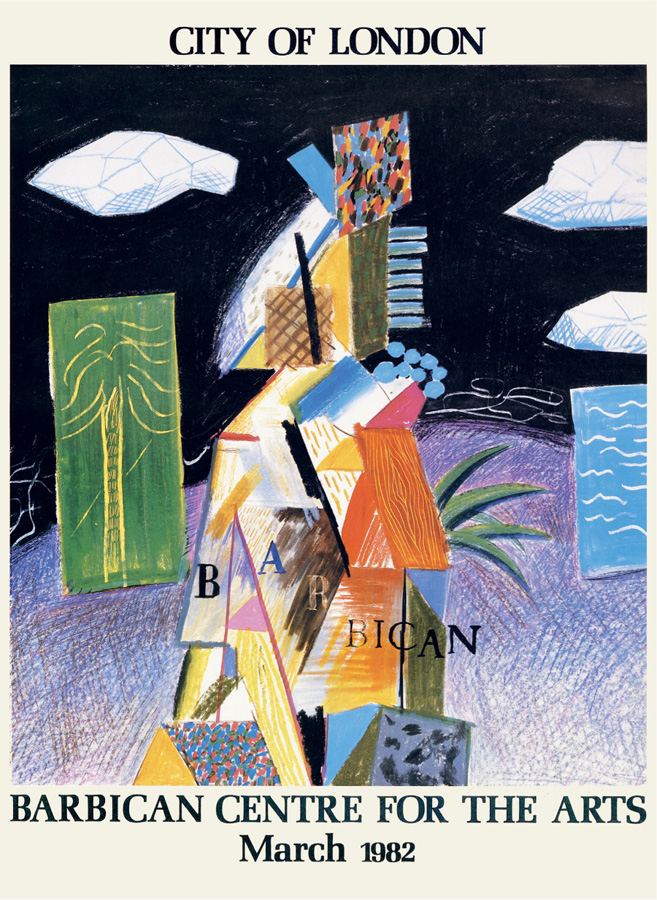

Poster by David Hockney for the opening of the Barbican, March 1982.

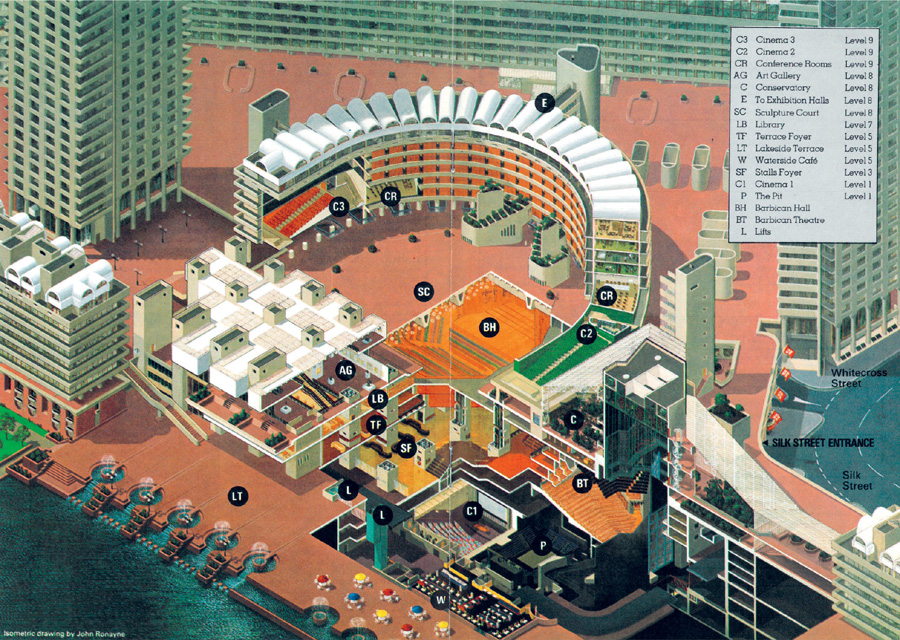

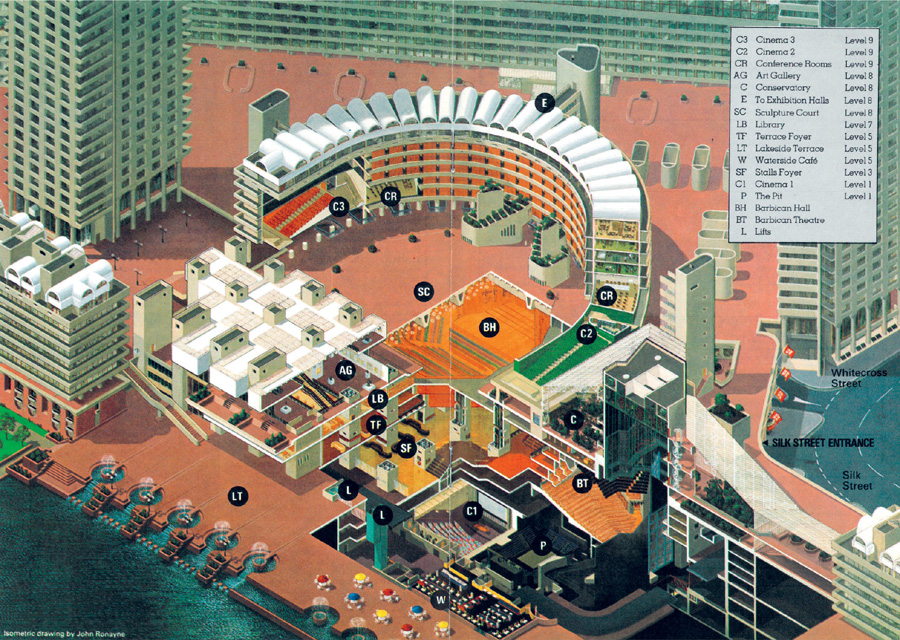

Isometric drawing of the Barbican Arts Centre as built, by John Ronayne, August 1982.

Foreword

Fiona Shaw

Barbican

The outer defence of a castle or walled city,

A double tower above a drawbridge.

Its not even a lifetime ago that the Barbican opened its invisible drawbridge to the public, yet in that time the Barbican has become as permanent as the ruins of the London Wall on which it stands. The building is enigmatic a contradiction. It is a bastion protecting the many sources of energy that create pieces of performance; yet it opens outwards with a rare power and directness.

Theatre and the arts have radically changed their nature in the past 40 years, and the Barbican has been part of that change by gathering outside influences, inviting artists from all over the world, nudging local talent to expand the methods and the outcomes of the form, expanding the range of discourse and the meaning of our work.

In a world lately battered by economic inequality and pandemic, in a moment when we have become less international than at any time in memory, the Barbican is a preserver of the multinational democracy which is art.

This democracy has been delivered as a dazzling ongoing festival, thanks to the appearances of so many great artists of our time. In my world of theatre, Ninagawa has infused spectacle with scale and feeling, Shakespeare as owned by the world and redelivered to us by the innovation and intercessions of Ivo van Hove and Thomas Ostermeier.

For me, the greatest fundamental shift in approach should be attributed to Pina Bausch. She did this in dance, without spoken language the lifeboat that has kept British theatre afloat. Like Peter Brook, her gift to the theatre will go on resonating over the next decades as the performances she brought to the Barbican transformed the approach to all theatre. She delivered the irony of the ordinary and the tragedy of the domestic. She slowed the moment down to its essence and we saw ourselves again. The North Americans too have told their story on this stage. Laurie Anderson with her music and hypnotic abilities, and Bob Wilson who has pushed aesthetic value towards a painterly meditation. Peter Sellars, who skims meaning in his semi-staged concert operas with Simon Rattle, shows how much can be expressed in a short time, just as Robert Lepage shows us what years of process can reveal in theatrical ingenuity.

It might seem naive now, but back in the 1980s we were very fired up. The RSC expanded from the country pleasures of Stratford and came to the Barbican. When I arrived it was only two seasons old, and its early reputation among the RSC actors was as a very luxurious, but terrifying building. It was daunting. The stage door hidden like an afterthought, a mouth halfway down the ramp to the car park. Backstage we were like colts, faltering and lost on the staircases and the inhospitable corridors. The theatre covers a depth of five floors that were arrived at by a lift that took us down underground to the Green Room with its dark floors, next to that the windowless rehearsal room where we spent so much time, like canaries in a mine.

But we produced living work. We believed we were challenging outdated attitudes. Feminism had finally begun to affect performances on stage. Language, and its male values, were being questioned. It felt like a structural shift; women characters could no longer be just in relation to men as daughters, wives or mothers. The frontiers of their possibilities were as infinite as for the men. This was challenging with Shakespeare, a writer who often makes his women characters silent once they have agreed to marry, so the actress heroines of the plays carried a huge responsibility in what we were reflecting during that shifting time; politically we were influenced by the recent miners strike, which had left a wave of frustration and a need for rejuvenation.