THE BIG APPLE HAS BEEN CALLED THE BIG APPLE FOR GOOD REASON. New York has remained the most populous city in America since the first U.S. census delivered such information in 1790. So it is far from mind-boggling that the metropolis successfully supported three major league baseball teams for much of its history while other fan bases barely backed one or even suffered from such attendance woes that they were forced to leave town.

That does not mean New York clubs have appreciated the competition. Such was certainly true as the 1903 season approached. Giants owners Andrew Freedman and John Brush turned no cartwheels when local saloon proprietors Frank Farrell and Bill Devery, who had opened several drinking establishments and gained greater wealth organizing a bookmaking and gambling ring for horse racing, offered $18,000 to buy the failing Baltimore Orioles of the fledgling American League. Never mind that the Giants resided in the National Leaguethey already competed for attention and consumer dollars with the Brooklyn Superbas.

Brush proved powerless in his desire to prevent the purchase. AL president Ban Johnson desperately sought an eighth team after the Orioles declared bankruptcy. So the New York Highlanders were born on March 12, a mere six weeks before the regular season began. One could only imagine the reaction of Farrell and Devery had they known that the worth of their investment would eventually grow to $4.6 billion and their franchise would become the most valuable in the history of American sport.

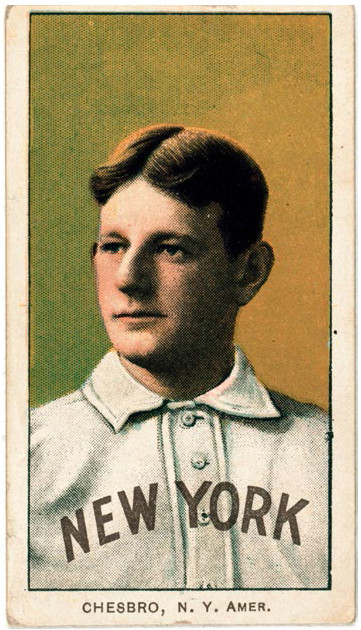

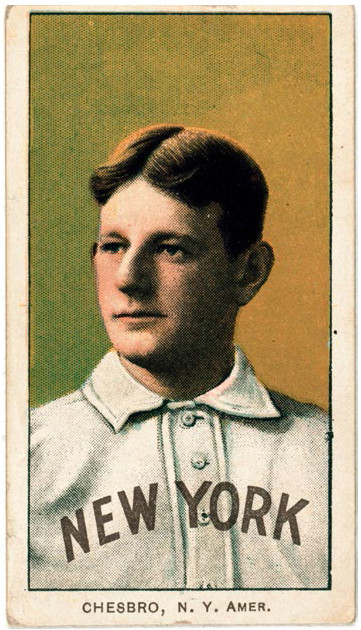

The club would have to wait to assume its legendary nickname. Its original moniker was inspired by home field Hilltop Park, which was located on a hillor high land. The venue, hurriedly constructed in six weeks on the corner of Broadway and 168th Street, remained unfinished and quite the mess upon its unveiling. Its 500 builders did not even have time to grow grass for the outfield. It was not exactly besieged by patrons in its first season as the Highlanders finished seventh in American League attendance. A comparative throng of 16,243 arrived to watch budding superstar right-hander Jack Chesbro beat Washington, 62, in the first home game, but that proved to be the only five-figure crowd that year. The offensive hero of the day was aging outfielder and fellow Hall of Famer Wee Willie Keeler, who had bolted the Superbas for the Highlanders and scored three runs.

Jack Chesbro won a league-best 41 games in 1904 and remained a standout for New York for four more years. COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

One could only speculate how early franchise history would have been affected had legendary John McGraw taken his managerial talents from Baltimore to the new American League club. He instead landed with the Giants and guided that team to ten pennants and three World Series championships. The Highlanders were instead stuck with Clark Griffith, whose nephew and adopted son Calvin gained fame decades later by spearheading the move of the Washington Senators to Minnesota and remaining owner of the Twins for more than twenty years. The elder Griffith took the Highlanders on a roller-coaster ride, alternating winning and losing records annually from 1904 forward until Farrell fired him in 1908. The dismissal under the weight of pitching woes and locker-room disharmony came as a surprise to Griffith, who had entered into an unwritten agreement with Farrell that he would not be canned during a season.

Griffith certainly bought himself time at the helm in 1904 when his team overachieved in taking the Boston Americans down to the wire in a heated pennant race, though the brilliance of Chesbro, who used a spitball and change-up to maximum effect, played the most significant role. The rotation ace established an American League record that seems certain to stand forever with 41 wins and led the junior circuit with a 1.82 earned run average. But Griffith earned credit by guiding a club that ranked middle-of-the-road in both runs scored and allowed to the brink of a title. That proved quite a feat considering that infielder Jimmy Williams, who seemed destined for a Hall of Fame career, continued a slide toward mediocrity that began when he and the franchise left Baltimore the year before.

Such a heady achievement for the Highlanders appeared unlikely when they lost five of six to fall 5 games out of first place in mid-July. But they embarked on a 9-1 stretch two weeks later and remained in a nip-and-tuck battle with Boston the rest of the way. The schedule-maker had heightened the tension by booking the combatants for five head-to-head clashes to end the regular season that included two doubleheaders in New York. But Farrell foolishlyand presumably with the belief that his club would not be fighting for the pennanthad rented out Hilltop Park for a Columbia University football game, forcing the Saturday twin-bill to be played in Boston.

Clark Griffith served as Highlanders manager for six seasons. COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

One can only speculate on the impact of the venue change after Chesbro had pitched the Highlanders to a Friday victory to push his team a half-game ahead. But the Americans rose to the occasion, sweeping the doubleheader at the Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds, including a 132 pounding of Chesbro, who insisted on pitching on no rest, and a 10 shutout by the immortal Cy Young. They polished off New York the following day by again beating Chesbro, who uncorked a wild pitch in the ninth inning to allow the winning run to score.

A victory would have kept the Highlanders alive for the pennant but would not have resulted in a World Series showdown against the Giants. Brush, who had taken over sole ownership of that team, refused to participate in the second Fall Classic, asserting that the American League was inferior. Critics of the declaration claimed that in reality he simply did not want to risk losing to the upstart Highlanders should they have emerged with the American League crown.

Neither Brush nor their American League rivals had to worry too much about the Highlanders in the years that followed, greatly due to the fading of Chesbro. He threatened retirement after the 1904 season before contending he had developed a pitch that could take a sudden jump rather than steady rise, though he admitted it would take time to master. So confident was Chesbro that the new offering would forever alter his repertoire that he gave away the secret of his spitter. But a sore arm derailed his best intentions, and a troubling weight gain that ballooned him to 200 pounds lessened his effectiveness.

Chesbro sported a 42-32 record over the next two years and led the AL in runs allowed in 1906. He returned his contract offer before the 1907 season with the explanation that he planned to work the sawmill and timberland he had purchased in Massachusetts at the turn of the century. It promised a heftier income. He changed his mind and signed two weeks into the season, but his career die had been cast. He finished that year with a .500 record and lost 20 games in 1908. Rumors that he would be demoted to the Indianapolis farm club in 1909 again motivated Chesbro to threaten retirement. He held out of spring training, returned in late May decidedly fat according to one newspaper account, and was soon out of baseball.

The Highlanders were a mess by that timeand the firing of Griffith after an 8-24 run following a promising start in 1908 had worsened their standing. His dismissal in favor of player-manager Norman (The Tabasco Kid) Elberfeld sent the club reeling further. The team lost a disturbing 62 of 72 games during one stretch that year and finished dead last with a 51-103 record.