First Mariner Books edition 2016

Copyright 2015 by Bill Pennington

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Pennington, Bill, date. author.

Billy Martin : baseballs flawed genius / Bill Pennington.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-544-02209-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-544-70903-4 (pbk) ISBN 978-0-544-02294-2 (ebook)

1. Martin, Billy, 19281989. 2. New York Yankees (Baseball team)History. 3. Baseball managersNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 4. Baseball playersNew York (State)New YorkBiography. I. Title.

GV865.M35P46 2015

796.357092dc23

[B]

2014039677

Cover design by Laserghost

Cover photograph Olen Collection / Getty Images

v2.0516

To Joyce, Anne D., Elise, and Jack:

the best of patience, support, wisdom, and inspiration

Introduction

THE MULTICOLORED CHRISTMAS lights in the trees at the foot of the driveway dotted the crest of the ridge that is Potter Hill Road. You could see them from a distance of several hundred yards as you approached from beneath the riselittle bulbs of red, blue, and green piercing the snowy darkness.

At 5:45 p.m. on Christmas night 1989, as Billy Martins pickup truck turned toward home, the ornamental lights waved a holiday greeting, bobbing from the branches of evergreens that framed the path to his farm in upstate New York.

It was a peaceful country setting, calm and serene, but earlier a gusting wind had left a glaze on a road that had been plowed but was never completely cleared of snow. Billys pickup truck approached a sharp bend 100 feet before the driveway to his 150-acre property.

It took no more than five seconds, but this is when and where Billy Martin died. With an ill-timed turn of the steering wheel, Billys Ford truck slid off the road into a ditch, then lurched forward until it crashed into a five-foot-wide culvert and bridge that spanned the trench. The truck came to a halt at the foot of Billys driveway, the Christmas lights that he had hung in the trees reflecting on the vehicles crumpled blue hood. Slumped inside, Billy had fractured his neck when he slammed headfirst into the windshield.

Twenty-four hours after the accident, on December 26, 1989, I drove to the scene. I stood at the end of the driveway and bent over to pick up a piece of headlight glass gleaming in the snow. It was quiet, a kind of rural quiet, and the hush and bitter cold accentuated the isolation of the landscape.

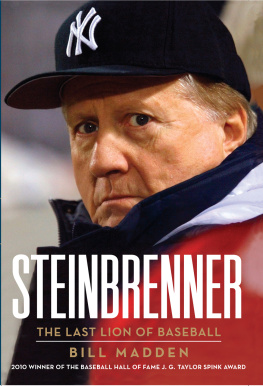

Inconceivably, Billy Martin, the big-city, bright-lights manager cheered by millions in his time, which included five loud stints as a central character in George Steinbrenners 1970s and 1980s mix of follies and championships, had died in the still of a lonely, pastoral road.

Billy would probably be alive today if he was wearing a seat belt, Ken Billo, an officer in the local sheriffs office, told me at the crash scene.

Perhaps thats true, but if there was anyone who went through life without a seat belt on, it was Billy Martin.

And yet, standing next to the nondescript, barren piece of country road just north of Binghamton, New York, I found it hard to believe that this was where it had all ended, the last act of a tumultuous life.

After all the firings, the suspensions, the fistfights, the dirt-throwing incidents with umpires, the hobnobbing with celebrities, the funny beer commercials and television appearances, the media wars and all the backbiting warfare in clubhouses and executive suites, it was natural to believe Billy was indestructible. He had wiggled his way out of countless bar fights, close games, and back-alley tight spots. Then a slick country road sneaked up and claimed him.

As a Yankees beat writer from 1985 to 1989, I had traveled all over the country with Billy. I had been threatened by him, almost beaten up by him. I had also been charmed by him, benefited from his natural graciousness, and enjoyed being in his charismatic presence for countless hours on the baseball trail. It was my job to be at his side day after day, year after year, in hotel lobbies, team buses, and chartered jets, in ballpark offices before and after games and into the wee hours of the morning as Billyand the Yankees beatwas transported into a thousand bars, lounges, and saloons around the continent. In that time, I discovered that Billy was without question one of the most magnetic, entertaining, sensitive, humane, brilliant, generous, insecure, paranoid, dangerous, irrational, and unhinged people I had ever met.

In the more than twenty-five years since his death, I always pondered writing a book about Billy principally because I saw the fascination in peoples eyes when I told them stories about him. Across the decades, at cocktail parties or any gathering when I would be asked to tell tales from my more than thirty years as a sportswriter, I could always depend on Billy Martin to entertain and intrigue. No other single figure would draw people in, or get as many laughs, or leave listeners puzzled and curious. He was someone they could visualize instantly, a character they knew as genuine and yet flawed, with a common-man vulnerability that set him apart. Billys emotions, ever so apparent, would seem to make him an open book, but his actions left a different impression, one both undefined and hauntingly mercurial.

At the same time, it was the lack of orchestration or affectation in his life that gave him a deeper appeal. Billy was beloved because he represented a traditional American dream: freedom.

He lived independent from rules. He bucked the system. He lived the life he wanted to live, despite the many personal costs. People admired him because he did what they wished they had the courage to do.

He told his boss to shove it. Often.

Unafraid of failure, he repeatedly faltered, then resurrected himself to succeed again.

He never backed down, even when to do so would have been an act of self-preservation and career conservation.

He was the hero, the antihero, and the alter egoor some combination of all threefor several generations of American sports fans, as both a player and a manager.

Born in a broken home surrounded by a shantytown, he was raised with fists clenched, ever ready to mete out punishment aimed at resolving the societal inequities he saw in his hardscrabble life. Rescued by sports, he found a mentor in Casey Stengel, who made him a professional athlete and eventually a Yankee, where he found success as a scrappy, beloved, and clutch player. For the next four decades, no one in baseball ever ignored him, least of all his legion of fans. He was not the kind of guy you could, or should, turn away from.

This was true right up to the last seconds of his life. Just before making the final turn in the road near his farm, just before the concluding twist in a life of many curves, Billys truck rumbled past the Hickling farm on Potter Hill Road. There was a beep of a horn and a wave.

He always waved or stopped to talk to you, Colleen Hickling said later. Then she added something that could have summed up Billys sixty-one-year life: Billy wasnt going to ignore you; he would always try to catch your eye.

At that he succeeded. He spent forty years catching peoples eye and came in close contact with practically every prominent figure in the history of twentieth-century baseball. He played for baseball royalty in the games Golden Age. He was the other second baseman in New York in the 1950sopposite the Dodgers Jackie Robinson, who went head-to-head against Billy nearly every fall in the World Series. He managed more than thirty Hall of Famers and revived a browbeaten, demoralized Yankees franchise in the late 1970s. He made memorable television commercials and movie appearances, gambled with Lucille Ball, played pool with Jackie Gleason, golfed with Jack Nicholson, and lived on the back page of the New York tabloid newspapers. He could talk for hours about Civil War history and Robert E. Lees battlefield strategies just as easily as he could explain the history of bunt coverage schemes dating to the 1800s. He never refused autograph seekers, would sit for hours in hotel lobbies talking with children, and slipped clubhouse boys and valets $100 bills like they were nickels. His smile, natural and unforced, could disarm any audience, from the field at Yankee Stadium to the couch on Johnny Carsons

Next page