THE TRIALS OF EROY BROWN

THE

TRIALS

OF

EROY

BROWN

THE MURDER CASE THAT SHOOK

THE TEXAS PRISON SYSTEM

MICHAEL BERRYHILL

Publication of this work was made possible in part by support from the J.E. Smothers, Sr., Memorial Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2011 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2011

Requests for permission to reproduce material

from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berryhill, Michael.

The trials of Eroy Brown : the murder case that shook the Texas prison system / Michael Berryhill. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Jack and Doris Smothers series in Texas history, life, and culture ; no. 31)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-72694-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-292-73876-8 (e-book)

1. Brown, Eroy. 2. Prison homicideTexasCase studies.

3. Prison administrationCorrupt practicesTexasCase studies.

4. Trials (Murder)Texas. I. Title.

HV9475.T4B47 2011

364.1523092dc23 2011021428

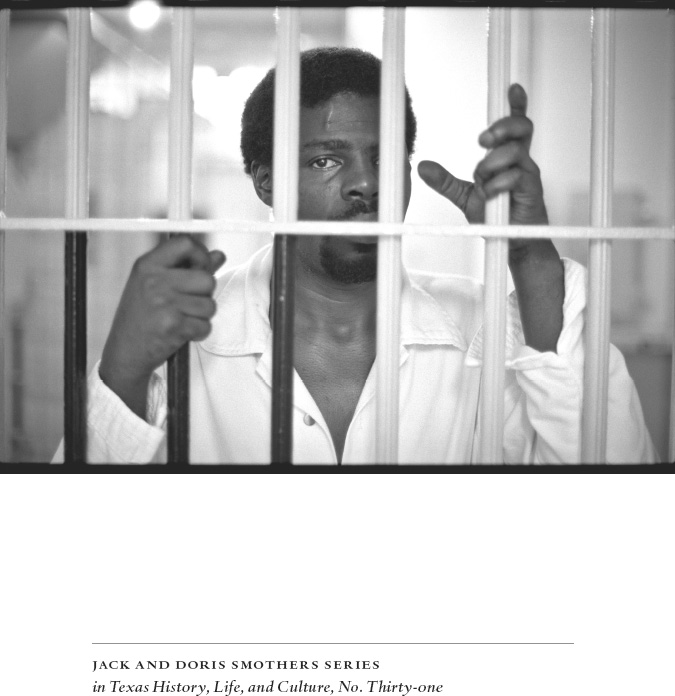

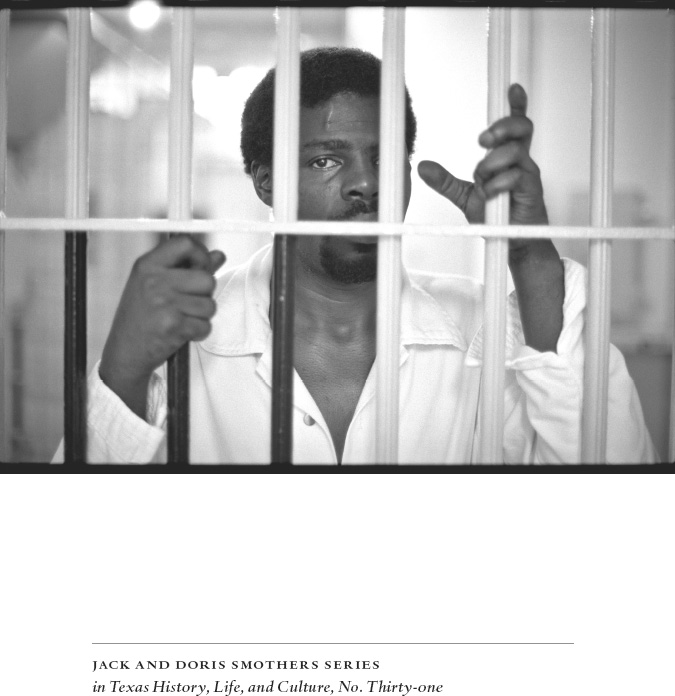

FRONTISPIECE: Eroy Brown. Photograph by Michael OBrien.

For Lynn, who made it possible.

In memory of Molly Ivins, who always said it was a great story.

The historians task is not to disrupt for the sake of it, but it is to tell what is almost always an uncomfortable story and explain why the discomfort is part of the truth we need to live well and live properly. A well-organized society is one in which we know the truth about ourselves collectively, not one in which we tell pleasant lies about ourselves. ||| TONY JUDT

If you put good people in a bad place, do the people triumph or does the place corrupt them? ||| PHILIP ZIMBARDO, THE LUCIFER EFFECT

PROLOGUE

VICTORVILLE, 2010

The visiting rules at the Federal Correctional Institution at Victorville, California, are strict: no cameras, no recorders, no cell phones, no scanty clothing, no hats, no do-rags, no billfolds, no car keys. For most visitors, no notebooks or pens, either, but I have been allowed to bring one of each. I left three pages of typed questions in the rental car. One condition of my visit was no extraneous paperwork.

It was the Saturday before Easter, 2010, and it had taken several weeks to arrange an interview with Eroy Edward Brown. The visitors center is a concrete-block room the size of a high school gym, with a video camera stuck in the highest corner. The guards, dressed in blue, watch the visitors and the inmates from a platform. The inmates, dressed in khaki, emerge from the back corner of the room, where two bright murals have been painted. One depicts a mountain lake with swans in the foreground. The other features a mob of cartoon characters to amuse the visiting children: Mighty Mouse, SpongeBob SquarePants, Batman, Superman, the Simpsons. Two ogres, Shrek and his wife, dominate the center of the mural, cuddling their green baby.

Eroy Brown emerges from the corner, looking around for me. It had been ten years since we last visited at the federal prison in Beaumont. His head is now completely shaved and gleaming. His close-cropped beard has gone salt and pepper. He wears a gray long-john shirt under his short-sleeved khaki shirt, sharply creased khaki trousers, and thick black work shoes. He had requested to be moved to Victorville from Beaumont.

Beaumont has all the most dangerous men in America, he says.

Although he has uneventfully spent the last twenty-five years in federal prisons, Texas parole officials would probably argue that Eroy Brown is one of those dangerous men he wants to get away from. That has to do with something that happened thirty years ago, when in an instant he chose to defend himself against a Texas warden who had pointed a gun at his head. At least, thats the story Eroy Brown told, and the story thirty-five of thirty-six jurors believed. After studying the case for the past ten years, I believe him, too.

Browns capital charges filled Texas newspapers and airwaves during the early 1980s, the same time that Texas inmates won a massive civil rights trial in federal court and changed the way their prisons were run. In that case, Ruiz v. Estelle, or more simply, Ruiz, a federal judge believed that inmates were telling the truth about the unrelenting cruelty of the Texas prison system. The major studies of the Ruiz case mention Eroy Brown in passing, a sentence here, a paragraph there, an endnote. Browns case replayed many of the issues that had been tried in Ruiz. That a black inmate could kill two white officials and not be convicted of murder shocked the prison system and marked the end of Jim Crow justice in Texas.

Prison officials never got over Browns exoneration. In his memoir, former Texas warden Jim Willett recalled being present when Brown was brought to the prison hospital with a gunshot in his foot.

He looked scared, Willett wrote. Later I learned more of the sad story. In the Ellis farm shop, farm manager Billy Moore had a problem with inmate Browna problem serious enough that Moore called the warden for help. The two men attempted to handcuff Brown, who somehow grabbed Packs pistol. In the scuffle, Brown apparently shot and killed Moore, then overtook Warden Pack and drowned him in the nearby creek. How the prisoner himself came to be shot remained a mystery.

When Browns trial came to court, I sat in the gallery with other prison employees, all of us there on our own time. When Brown was acquitted of murder charges, the verdict hit us like a kick in the stomach. We were numb. We watched justice lurch horribly awry, and we were angry.

Another former Texas warden, Lon Glenn, wrote in his history of Texas prisons that Brown had obtained a pistol from the wardens car while being transported. Browns lawyer, a controversial minority senator from Houston, put every convict who had ever had a grudge against the warden or TDC on the stand to cry and whine about how brutal the system had been to them.

For those of us who understand the realities of the Texas prison system, Glenn wrote, this was a clear case of injustice. We were left knowing that a

Brown has spent the last twenty-five years in prison for being an accessory to a convenience store robbery in 1984 that netted twelve dollars and a couple of candy bars. He was given ninety years as a habitual criminal. The two accomplices who testified against him got nothing.

For his own protection, he has served his time in federal, not Texas, prisons. But his fate still rests with the Texas parole board. Brown almost got parole in 2000, until someone reminded the board about his past. What he is really in prison for, he believes, is not for being a robber, but for defending himself against two Texas prison officials in 1981.

Brown seemed more expansive than last time I talked to him, when he was more guarded and cool. He resembles the actor Danny Glover a bita darker, contemplative Danny Glover, who smiles reflexively as he talks, and continually chews a plastic toothpick.

Next page