Showman: The Life of David O. Selznick

What to wear? Bringing Up Baby (1938)with Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, May Robson, and a naked wire-haired terrier. But everyone was wired in delicate situations like this.

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A . KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by David Thomson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thomson, David., [date] author.

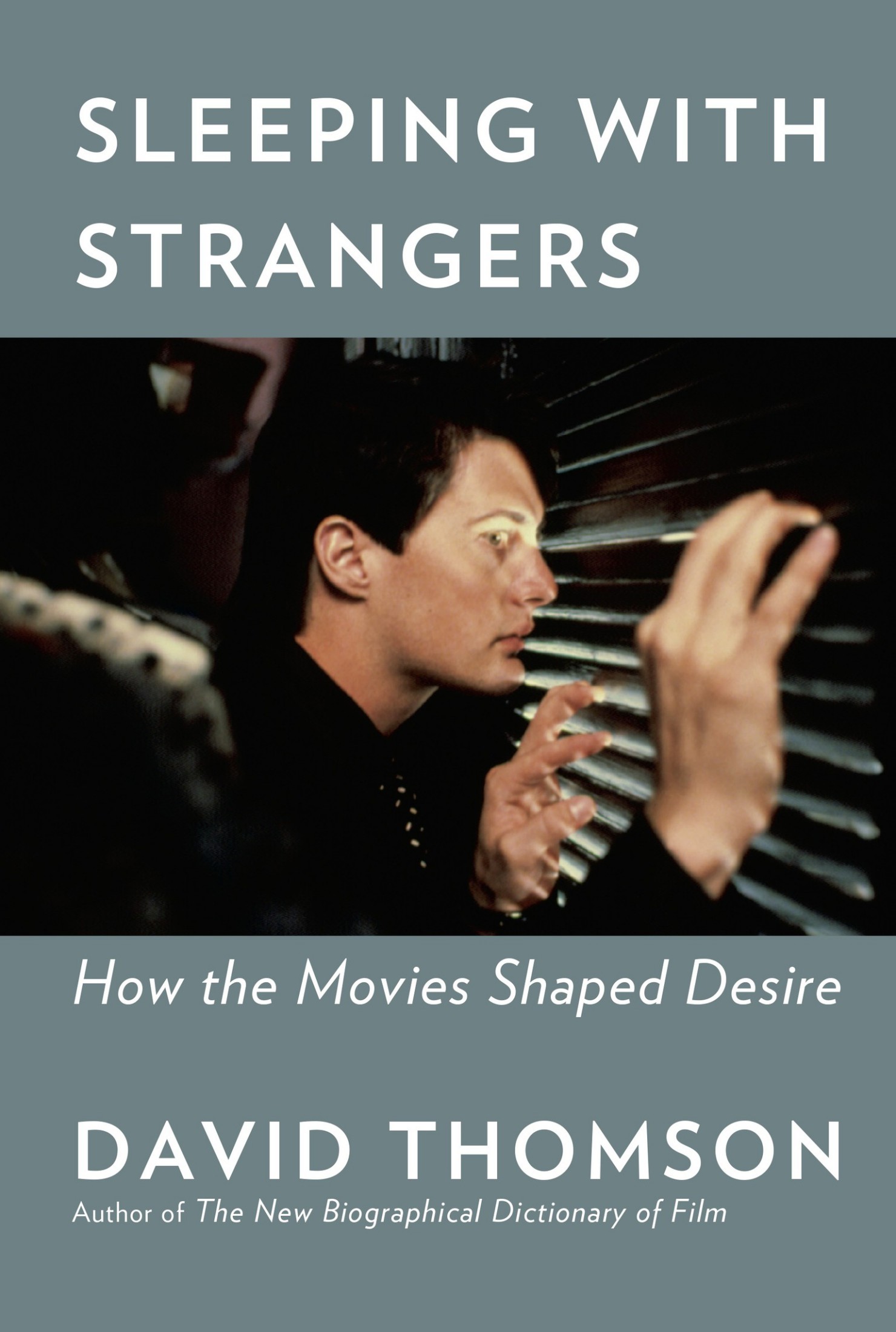

Title: Sleeping with strangers : how the movies shaped desire / David Thomson.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018017604 | ISBN 9781101946992 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101947005 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Men in motion pictures. | Machismo in motion pictures. | Homosexuality in motion pictures. | Women in motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN 1995.9. M 46 T 57 2019 | DDC 791.43/65211dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018017604

Ebook ISBN9781101947005

Cover image: Blue Velvet 1986 Orion Pictures Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of MGM Media Licensing. Print: Everett Collection

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v5.4

ep

For Kieran Hickey

The condition of memory, that painful place to which we return over and over because a fundamental question is still unresolved: something happened to us years ago which was important, yet we hardly know if an angel kissed us then, or a witch, whether we were brave or timid.

N ORMAN M AILER, A Course in Filmmaking, Maidstone, 1971

Because I just went gay all of a sudden!

D AVID H UXLEY (Cary Grant) in Bringing Up Baby, 1938

This business, movies, is all about two thingspower and sex. And guess what, theyre the same thing.

P ETER G UBER, 1989

Psychologically Im very confused, but personally I dont feel bad at all.

K LARA N OVAK (Margaret Sullavan) in The Shop Around theCorner, 1940

Contents

I NTRODUCTION

Naked at the Window

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty set up as Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Its a production still that knows what the movie is about, including the uneasiness within the couple. Fifty-two years later, Bonnies hurt look is explained: she told his storybut what about hers? Its time.

T HE MOVIE SCREEN IS A WINDOW, and the trick of the medium is to let us feel we can pass through it. I saw this film five times in a week in 1967 in London. Did it change my life? It ruined it. Made me a prisoner of desire.

The picture is set in a wild Southwest, some time ago. Two young animals meet and sniff each other out. They are so vivid, and their display is so emphatic, it has to be a movie. It sayslook! The animals feel an urge to mate. That seems natural, biological, and cinematic, but then the male turns uneasy. This distresses her, and it saddens him. Still, their companionship prevails and they become fellow-raiders in their terrain. This makes them notorious and hunted, until she sings a song about their fame. That frees him. They fall in love. Then they do it, as so many have done. It. They really get it onwhatever it is. An idyll follows before vengeful guardians of order in the terrain find them and slaughter them. So the pair die together, a legend of outlaw sex and violence.

This is not the only way to describe Bonnie and Clyde (1967). You could say its about two underprivileged kids finding attention and loot in Oklahoma and Texas in the early 1930s. Its a fable of Depression and self-expression such as we believe we deserve because the U.S. insists on the pursuit of happiness: that has been one of humanitys best daft ideas, though other cultures regard it as fatuous immaturity. That figures, because America, the movies, and Bonnie and Clyde are all resolutely youthful.

We are in a shabby bedroom in 1931 in the sketchy outlands of West Dallas. That year has been established with still photographs of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Except that these pictures are sepia lookalikes for 1931 in which Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty are pretending to be the two outlaws. Retrospective selfies. Photographs of the real Parker and Barrow do exist. They hint at poverty, hardship, the heat and dust of Texas, and its awesome distances in which it was easier to feel lost than found. The real Bonnie and Clyde might never have got past waiting tables in Midland or Odessa.

Bonnie looks sharp-faced and poverty pretty; she is narrow-eyed with a closed-mouth smile, and no makeup. She was certainly not the wide-eyed, drop-dead Faye Dunaway, the first person we see in that dusty bedroom.

Dunaway was twenty-six in 1967. She had gone to the University of Florida before graduating from Boston University. She had been in theater in the East for several years and Elia Kazan had cast her in a small part in his 1964 production of Arthur Millers After the Fall. She was a unanimous knockout: that was in her physical being and her professional and cosmetic training. No one made movies in 1967 without a knockout as the female lead.

Knockout is an important word; it may even be disastrous. No matter that they were said to be lifelike, movies then were crowded with exceptional lookers. The culture quickly raised them to be the best-known people in the world. But a strange dysfunction came into being. The world at large was not populated with knockouts. Most of us looked ordinary or homely and felt some shame about that in the light of the screen. Though America was avowedly egalitarian, it had created a way of being seen that cut across any hope for humble human value with the flourish of a holdup.

This unnerving contract exists in the way Bonnie is discovered and Faye revealed. We are observing a fictionalized character and a real actress, but on first sight it is the actress we see. She is looking in a mirror, applying lipstick, so we see her face and its urge to be more beautiful. That mirror is a version of the flat screen we are looking at: its presence makes us more aware of our own watching. The mirror can be a character or a conscience in movies.