About the Author

David Thomsonwhom Michael Ondaatje has called the best writer on film in our timeis a frequent contributor to The New York Times, the Guardian, and more. He is the author of The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, now in its sixth edition, and Moments that Made the Movies.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Moments that Made the Movies

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

First published in the United States of America in 2016 as Television: A Biography

ISBN: 978-0-500-51916-5

by Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

and in the United Kingdom by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

Television: A Biography 2016 David Thomson. All rights reserved.

This electronic version first published in 2017 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

This electronic version first published in 2017 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

eISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77372-7

eISBN 978-0-500-77371-0

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com

: Poltergeist, MGM/UA/Photofest.

FOR MARK FEENEY

Ordinary life was touching still, but science-fiction was happening. You could call that technology. But an oven of fiction, a virtual reality, had opened. And we wanted to be in it.

CONTENTS

The invisibility to posterity has always been televisions difficulty. Many programs are intended to be disposable, to disintegrate even as you look at them.

MARK LAWSON

Its an incredible gauge of the generic. If we want to know what American normality isi. e. what Americans want to regard as normalwe can trust television. For televisions whole raison is reflecting what people want to see. Its a mirror. Not the Stendhalian mirror that reflects the blue sky and the mudpuddle. More like the overlit bathroom mirror before which the teenager monitors his biceps and determines his better profile. This kind of window on nervous American self-perception is simply invaluable in terms of writing fiction.

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

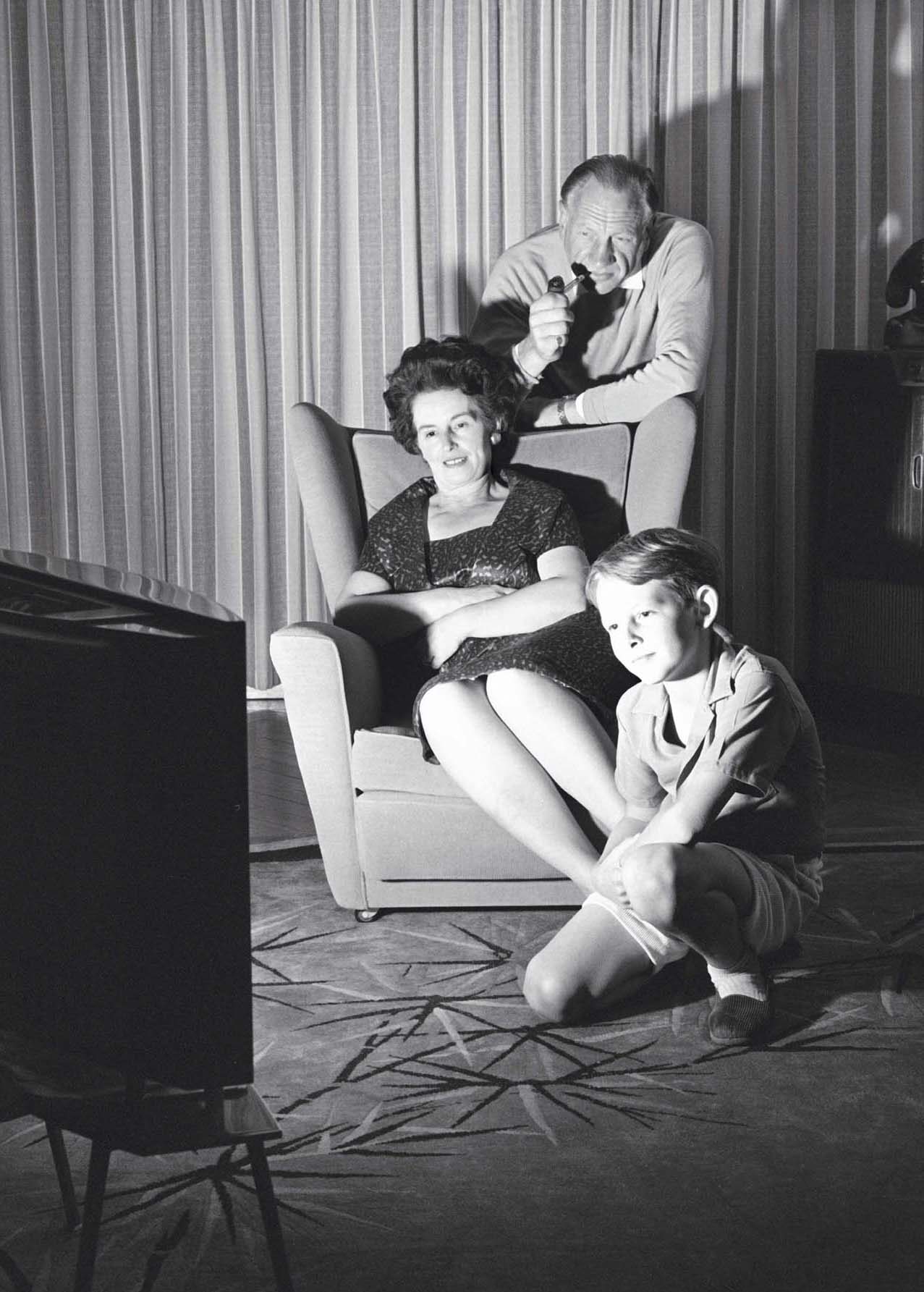

ITS OLDER THAN MOST OF US, parental yet uncritical, if not unconcerned. It poses as some kind of comfort, but you cant kid yourself it cares. So when did you start to think about television?

I admit thinking may be an inadequate word for what happened between you and this medium. So much that is formative in television has to do with the loose textures of ease or unthinkingIll go home and Ill watchand then Ill feel all right. As if you hadnt felt all right out in the world. How could you, with that horizon getting grimmer from 1914 onward? But televisions magic has always embraced safety, the possibility of useful intimate company, and the thought of time elapsing restfully but constructively. Its the sofa as church. Or rather, it is church reduced to the soft status of a sofa, minus guilt, redemption, or moral purpose.

There is this added, rueful comfort: Whenever you started thinking, it was too late. For the thing we used to call television doesnt quite exist now. The sacred fixed altar (the set) has given up its central place of worship and is now just one screen among so many, like the dinner table kept for state occasions in a life of snacking. The appointment times of TV have eroded; the possibility of a unified audience (or a purposeful society) has been put aside. In the dire 201516 presidential election campaign, it was obvious that the thingthe talent showhad found the frenzy of other game shows, with drastic but meaningless dialogue and monstrous celebrity better suited to daytime soap operas. As a democratic process it was not just shaming; there was the portent of worse to come, even a fear that the vote might be buried in some instant TV feedback derived from American Idol. You like to votelets do it all the time. Could such a game show go onforever? Because the media fed on it and felt some deranged fulfillment. The more debates, the less subjects were debated. Journalists were alive with jittery, spinning self-importance. They said the election was the most important everthat sweet dream. We knew it was just a nightmare show our trance had allowed.

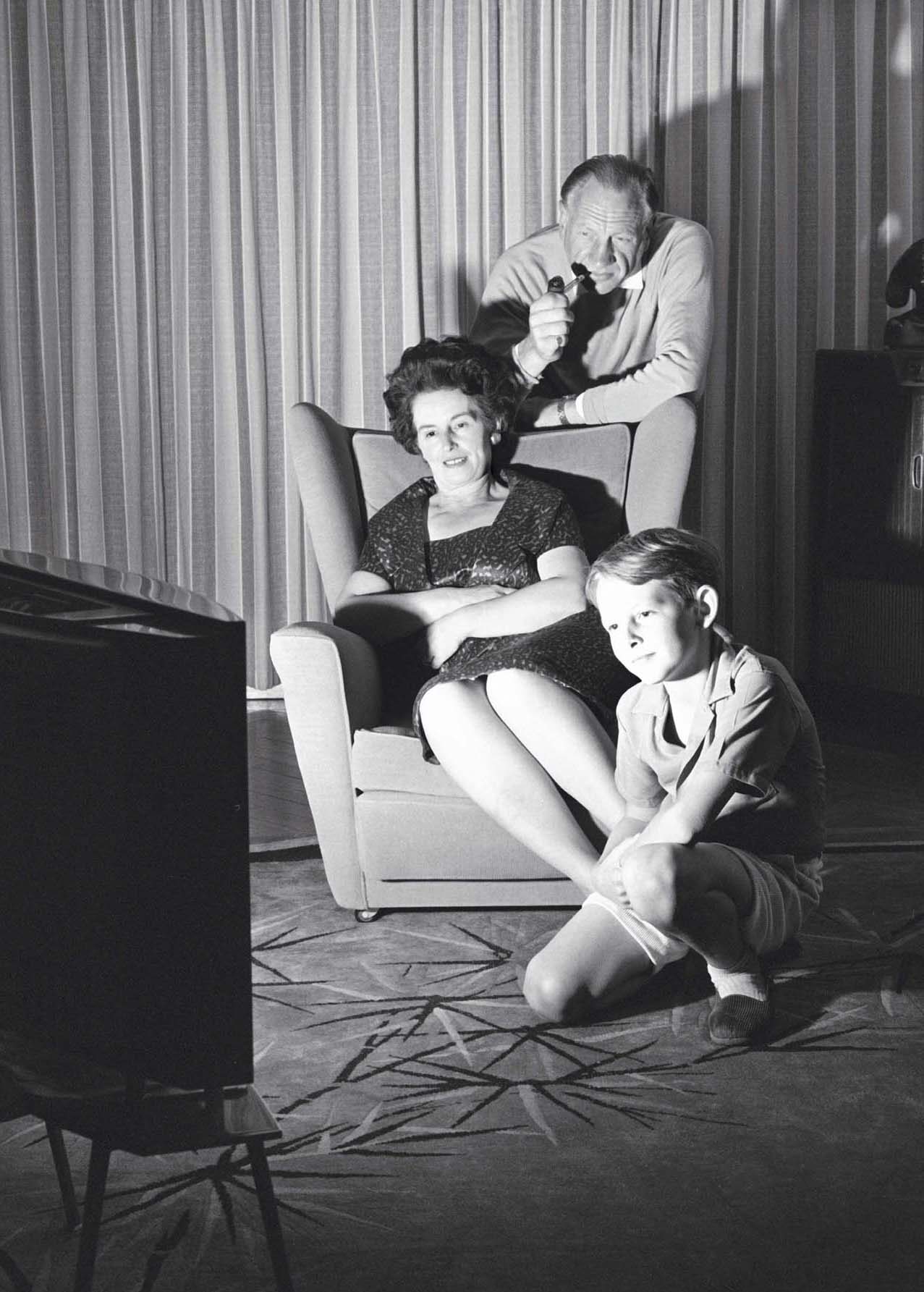

TELEVISION WASNT ALWAYS ON OR THERE. It had no place in the settled order of things. There was an ancient time, BT, after which the new word sounded rather sci-fi or gimmickylike plastic, the bikini, or the atom bomb. In other words, people wondered if the craze could lastbut then it spread, like weather.

The invention, or the quaint piece of furniture, wandered into our life in the 1940s, as a primitive plaything, a clever if awkward addition to the household. It was expensive, unreliable, and a bit of an invalid. Reception was so vexed and frustrating we laughed and scolded ourselves for being idiots. If we couldnt get its image to stay still, how could we foresee that it would devour us? Were hardly to blame, are we? We were used to movies and radios, which came on like shows and performancesversions of theater. Television would try that for a while, putting a stress on schedules and neurotic start times. But that was a ruse to hide the deeper importthat it was simply on or off. As with sex, reception gave way to absorption. Some shows flopped while others soared, but some people were content with the test card. Watching, criticism, judgment, meaningall those esteemed procedureswere on the way out.

The household pet of once upon a time became a strange, placid beingthe elephant in the room, if you likenot a monster that attacked us and beat its Kong chest in triumph but an impassive force that quietly commandeered so much of what we thought was our attention, our consciousness, or our intelligence. Television wasnt just an elephant in the room. It became the room, the house, and the world.

You can respond to this with alarm if you wish. (In theory, alarm is still available.) But the deepest nature of television is to be reassuring. That may be the most frightening thing about it.

I know, that doesnt seem to fit: How can reassurance be a source of anxiety? But doesnt one spur the other? We are selling our complex experience short if we dont take note of the modern pressure for impossible simplicity, like stopping fossil fuels or carpet bombing ISIS. In the course of this book, I will refer to screens having done so much to organize our experienceI mean our making our way by watching screens, or by having them on, hardly aware of how the television screen has trained us for the computer screen, the iPad, the iPhone, or even the iI (coming so soon I wish I had invested), and the assumption that because information is carried in those ways so knowledge must exist there.

Next page