Phil Norman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

There is no holding down the modern inventor. He rides the waves of the ether with the conquering skill of a master in a celestial rodeo. Give him a valve and there is no holding him. It is almost certain that within a few years we shall have all our entertainment available within our own four walls. Press but the button and a stereoscopic talking film will happen over the mantelpiece.

Seen and Heard , Manchester Guardian, 1 April 1930

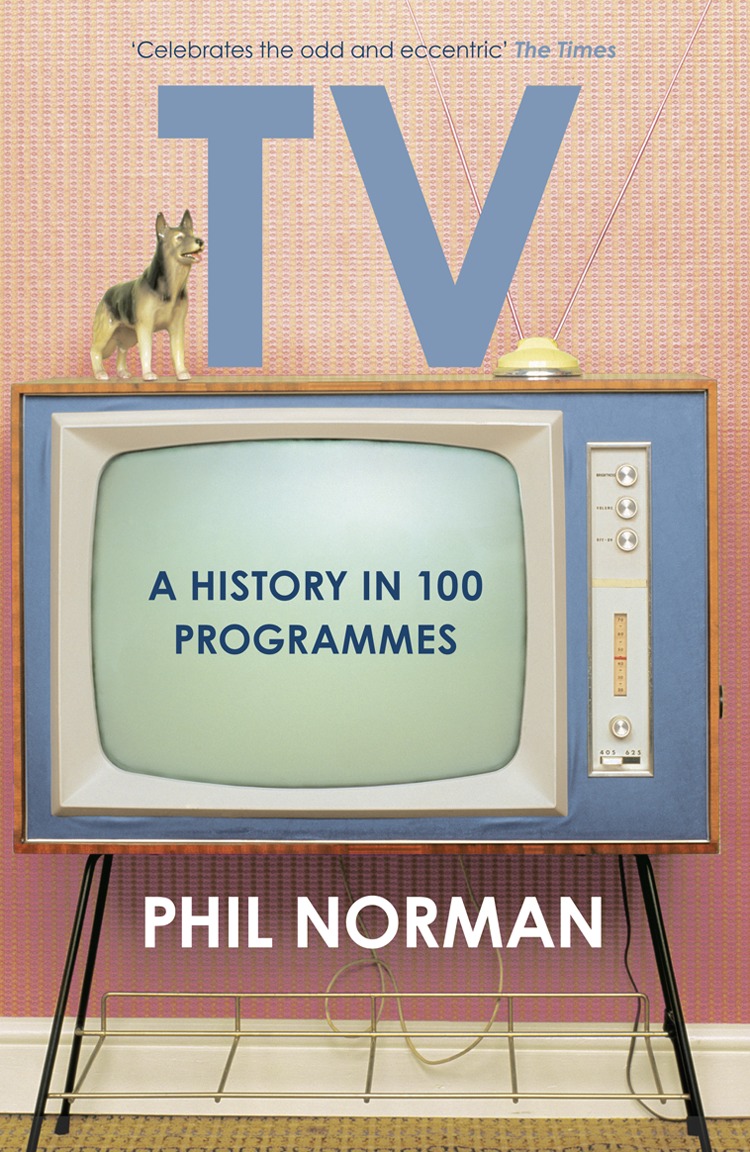

I T HAD AN AURA about it, a presence. By todays standards it was tiny, but it dominated the room in a way its technically superior descendants never quite manage. It catered directly for two of the senses, but in operation it affected them all. The flicker and the glare of the bulbous, grey-green screen. The hum and whine of the tube heating up. The crackle of static when it turned off, the tang of burnt dust in the air when it was repaired. For decades the television set was the most advanced piece of technology to be found in any house. How it worked was a mystery, but it was literally part of the furniture.

It was also an instant portal to a cavalcade of smart, witty house guests with inexhaustible supplies of information, anecdotes, opinions and vibrant sweaters. Miraculous and commonplace at the same time, television occupied a unique position in the national imagination. Detractors claimed it hijacked the national imagination formerly a cultural Arcadia of chamber music and well-made plays for its own base ends, but at its best it brought classes and cultures into each others homes without prejudice. By the late 1960s even the press admitted that TV, coming from nowhere, was beating them at their own game and several new ones of its own invention.

The birth of television in the mid-1920s garnered more fuss than a royal baby. The race to perfect a workable system was matched by the rush to predict imminent social catastrophe. Newspapers, radio, theatre and even the motor car (why drive somewhere you can see at the flick of a switch?) were pronounced doomed many times. Rumour and misconception abounded. Professor A. M. Low worried about the effect on international relations if Americans could use the new device to view their British neighbours engaged in frightful activities, such as drinking cocktails.

More usefully, Lodge worried about content, noting that the majority of messages sent by another recent scientific triumph the transatlantic telegraph cable were rubbishy. It is no use enlarging our powers of communication, he warned, if we have nothing worthwhile to say. The insubstantial nature of the early demonstrations didnt help even John Logie Baird provoked a wave of cheap laughs when he based his first telerecording demo around a cabbage.

Initially the preserve of the rich, the take up of TV spread after the Second World War as prices dropped and services improved. Older media, who had originally described it as an elitist fad for well-to-do stay-at-homes, now tried to dismiss it as a pernicious influence on those less stable, less educated than themselves. A snobbish line in the fifties had it that people were raising H-shaped aerials over their houses to make up for all the Hs dropped inside them.

It may have projected a serene, slightly aloof air on screen, but behind the cameras post-war television was paddling like mad, inventing a new medium on the hoof, often with whatever came to hand. Studios looked less like the glistening caverns of today and more like the shop floor of an engineering works under the stewardship of a hyperactive ten-year-old. A profession was being steadily built through years of committed bodging.

America initially lagged behind Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Russia and Japan in television take up, but soon made up for lost time. NBCs first electronic transmission in 1936, featuring comedian Ed Wynn, ignited an industrial boom that in little over a decade would result in four national television networks broadcasting to over four million set-equipped homes. The US network system, commercially funded and powered by the twin big tickets of sports and vaudeville, was voracious and unstoppable. By the late 1940s its diverse schedule offered programmes that were sombre ( Court of Current Issues, Peoples Platform ), sophisticated ( Caf de Paris, Champaign and Orchids ) and silly ( Buzzy Wuzzy, Campus Hoopla ).

This last category caused unease back in Britain, where ITVs arrival in the mid-1950s threatened the state-run BBC order. The US broadcasts of Elizabeth IIs coronation had included grinning appearances by NBCs mascot, chimpanzee J. Fred Muggs, and there were concerns about a similar crassness creeping in to British broadcasting. The Tories championed ITV, Labour vilified it, while Liberal councillor Paul Rose reminded both sides that there is always freedom of the knob.

Technological advance was an enduring obsession, if not always taking place as quickly as predicted: a committee set up in 1943 to prepare for British televisions post-war return anticipated the swift invention not only of colour, but 1000-line high definition and 3D.

Around this time came the first symptoms of two ailments that would dog the medium for evermore. The first was the transformation of the social embarrassment surrounding television among the middle classes into an ironic guilty pleasure. As John Osborne confessed to Kenneth Tynan in 1968, When TV is dreadful, its thoroughly enjoyable. After youve seen The Golden Shot a couple of times, it acquires a special horror of its own. The second, closely related to the first, was nostalgia. In the dying days of 1969, ITV screened A Child of the Sixties , taking the temperature of the decade with a rummage in the archive. This sort of thing was nothing new in itself, but for the first time whimsical talking heads were added, including the impressions they made on a receptive young mind an Oxford undergraduate named Gyles Brandreth. The bar for retro-punditry was set from that moment.

The study of television doesnt have to be so apologetic. Television may not be high art, but many artists have worked in it, regardless of its condemnation as unclean by the worlds cultural custodians. Samuel Beckett wrote for it. Kingsley Amis presented a pop music show on it. Carol Ann Duffy laboured in it writing cockney gags for Joe Browns snakes and ladders game show