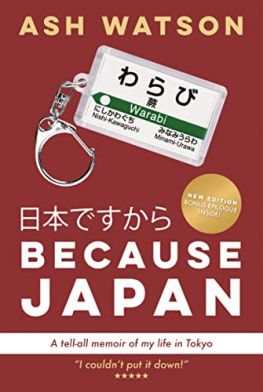

JAPAN

ASPECTS AND DESTINIES

At the turn of the twentieth century, the author spent three years in Japan, at the heart of what he saw as a revolution. The modernization of the Meiji era was well underway, but far from complete. All around him, Watson saw orientalism and feudalism jostling with the twentieth century, in strange juxtapositions that produced a melange that he found inspiring, disappointing and irritating but always interesting for, as he wrote, there had been no spectacle on earth like it since time began. While other observers of Japan wrote of the Old or the New Japan, or suggested that the transition from one to the other had been accomplished easily and gracefully, Watson set out to reveal all the contradictions, anachronisms, tragicomic consequences and peculiar manifestations of Meiji westernisation. His eye and pen are sharp, but his underlying concern is what the ultimate outcome of this enforced modernisation will be. The question always before him is can a nation forget its origins, identity and culture? Watson prowls the material and immaterial world of Tokyo, metropolis of the revolution, alert for dissonance. The Japanese dress reform movement produces costumes of supreme inelegance; the simplicity of the Japanese home is disturbed by the discords of European innovations, the bathhouses are no longer mixed. As the book ends, Watson sees constitutional government in Japan losing ground an intimation of the political events of the next half-century. This is a thought-provoking book, first for the unique account it gives of the contradictions and tensions beneath the surface of the accepted version of the Japanese modernisation narrative, and also for the questions Watson poses about the effect of westernisation of Japanese identity and nationality, as timely now as it was a century ago.

GUARDING CHILDISH FEET

[cartoon by the Jiji , the leading Japanese newspaper, on the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The children are China and Korea. The principal declared object of the Alliance is to guard Chinese and Korean integrity.]

First published in 2005 by

Kegan Paul International

This edition first published in 201 1 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0968-6 (hbk)

ISBN: ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0968-6 (hbk)

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint

but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be

apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright

holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been

unable to trace.

PREFACE

T HE first papers of this book were written in Japan fifteen months ago, with the writers mind innocent of a notion that the book must appear in the houralmost, as it seems, in the moment of a supreme crisis, possibly the supreme crisis, of Japans modern history, perhaps of all her history. The author began with a hope of executing something in the nature of a vignette of manners; at the most, or at the best, of executing a picture of the strange evolutions of a great political, industrial, social, ethical Ideathe Japanese Revolution. Circumstancesbut not circumstances alone, for there were the inherent seductions of the taskmake him responsible for something of the nature of a political, even a polemical, treatise. It is true, indeed, that any personal contact, however fugitive, with the current of Far Eastern politics in these recent times must have turned the eyes of any one possessing a spark of imagination, forward to the looming of the great trouble which at this moment engages the worlds thought and speculation, if not its moving anxiety. Therefore there was always the chance that this or any other book on Japan, undertaken in these recent times, might hit the psychological moment in full career, and, incidentally, load its writer at least with a suspicion of the repugnant guilt of manufacturing a book for an epochthat is to say, of deliberately and of set purpose lying in wait for the moment and ministering, with dubious private purpose and doubtful public benefit, to its unnatural needs. This onus the author repudiates without length of words. Events are chiefly guilty, not he. So much as this should be open to the candid reader in the book itself. What may not be so clear is the writers mind and admission about Japan. This is that Japan isincomprehensible, not to be understood. This, indeed, is one of the very tritest things he, or any one else, could say about Japan. Nevertheless, and having written his book, he says it. It is his confession. He does not understand Japan. This is the background of his book the incomprehensibility, the impenetrability, the mystery of Japan. The writer has made a book about that which he does not understand not a new precedent in literature perhaps. It is the person who stays three weeks or three months in Japan who understands it. The present writer, unfortunately for his hope of understanding it, spent three years in itin close, daily, arduous association with its people, with its problems, with its politics. Therefore he does not understand Japan. There is an Englishman of Tokyo who has spent three decades in Japan his sojourn unbroken by a single flying visit to his own country or to the nearer Americas. He has seen all, he has been in the midst of all, almost he has been an actor in all the wonderful events of the wonderful history of Japan since 1870, or thereabouts. He is a master of the Japanese tongue. He has compiled a great dictionary of the language. He is married to a Japanese lady; he has, if I mistake not, a son in the Japanese Army. He has just lately completed a work a Work on Japan in eight splendid volumes of infinite learning and scholarship. Yet this gentleman has on various occasions made public confession that he does not understand Japannot quite in so many words, perhaps, but clearly to this effect. And he and his high reputation were to be less esteemed if he made any other opposite profession. Hence may the present writer be absolved of the crime of an unseemly temerity in making a book about that which he does not understand. I have great, almost illustrious, exemplarsmen of my own race, of almost a lifetimes residence in Japan, who have made small libraries about Japan without having understood. Nescience is always bold, often presumptuous. Yet where is the limit of speculation in face of the Unknowable? There is no measure of the immeasurable, no plummet for the unfathomable. By this token I claim indulgence for my speculations in face of the Japanese Unknowablein plain terms for the views of Japan and the Japanese destiny set forth in my concluding chapters. I have, indeed, pleas, or a plea besides illustrious example in extenuation of the rest of the book. Wagners sayingI quote it appropriately from one of my exemplarsis: Alles Verstndniss kommt uns nur durch die Liebe. Love is certainly my plea, with understanding a question in abeyance, for I have confessed nescience. But, for these concluding chapters aforesaid, I make bold enough to claim that, at least, they take Japan, and the Japanese destiny, seriously. Hitherto the Japanese Unknowable seems to have given excuse chiefly for mirth. Because people have not understood, they have laughed. Ignorance, indeed, commonly laughs, but knowledge of ignorance, consciousness of it, ought to regulate another mien. Is it not time for us of Western Europe to know our ignorance; to recognise the Unknowable, and wear against it a more continent face, if as yet we find it difficult to adopt about it a more serious mind? Is it not time in these pregnant opening weeks of 1904? I might urge this, if nothing besidesthat by taking Japan seriously, we at least ensure against Japan taking us by surprise. I might urge more, but it must suffice that I bring a Bishop into the witness-box. After he had written his concluding papers, the writer by chance turned up among his notes and cuttings a letter of the Anglican Bishop of South Tokyo. If by quoting it he seem to deprive his own speculations of their originality, he at any rate secures a respectable ally for the defence of their probability. The Bishop of South Tokyo in 1901 wrote to his ecclesiastical confrres in England as follows: That the leaders here are absolutely settled and consistent in their intention that Japan shall be a Western, not an Eastern Power, in its methods and associations, and, so far as Western ideas are good, in its ideas also, seems to me about the most certain and stable fact in Japanese politics. But if this is so, then if Japan were to lead China, which does not look very likely at present, it would only be by regenerating China, and this would be done according to Western ideas except so far as these are deliberately altered for the better by the infusion of what is thought by Japan to be best in the Eastern. I do not think the probability of any such movement on a world-affecting scale likely in the near future, but if it did come, and Japan with China became a leading influence in the worlds thought and government, it would only be so because Japan, by taking out of its treasures things Eastern and Western, things new and old, had become the best leader for the next stage of human progress. I feel that by this Bishop I am justified. Upon his reverend authority, by this high episcopal example, I am not to be charged with eccentricity in taking Japan seriously, any more than I am to be charged with making a book for an occasion, because it happens that Japan is in the worlds eye when this book appears.