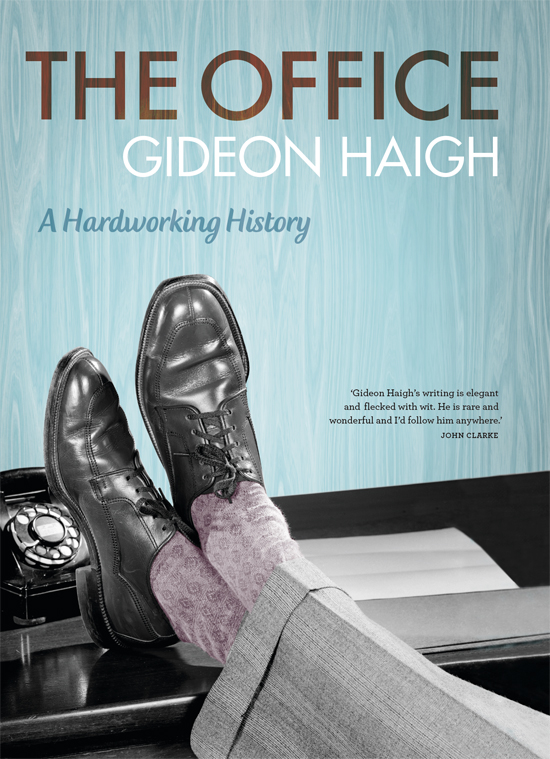

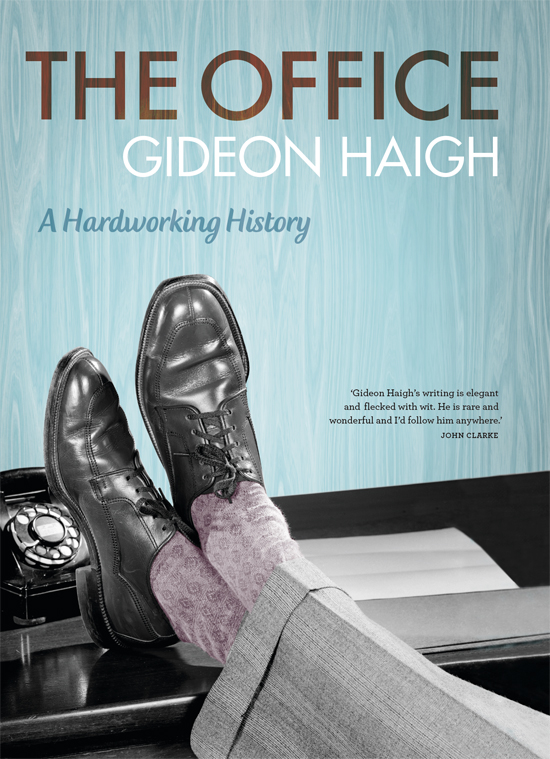

The office: for many of us, it's where we spend more time and expend greater effort than anywhere else. Yet how many of us have stopped to think about why?

In The Office: A Hardworking History, Gideon Haigh traces from origins among merchants and monks to the gleaming glass towers of New York and the space age sweatshops of Silicon Valley, finding an extraordinary legacy of invention and ingenuity, shaped by the telephone, the typewriter, the elevator, the email, the copier, the cubicle, the personal computer, the personal digital assistant.

Amid the formality, restraint and order of office life, too, he discovers a world teeming with dramas great and small, of boredom, betrayal, distraction, discrimination, leisure and lust, meeting along the way such archetypes as the Whitehall mandarin, the Wall Street banker, the Dickensian clerk, the Japanese salaryman, the French bureaucrat and the Soviet official.

In doing so, Haigh taps a rich lode of art and cinema, fiction and folklore, visiting the workplaces imagined by Hawthorne and Heller, Kafka and Kurosawa, Balzac and Wilder, and visualised from Mary Tyler Moore to Mad Men, from Network to 9 to 5plus, of course, The Office. Far from simply being a place we visit to earn a living, the office emerges as a way of seeing the entire world.

The Office: it's the history of all of us.

Born in London and based in Melbourne, Gideon Haigh has been a journalist almost thirty years, and written widely on business, sport, both and neither. The Office is his twenty-fifth book.

Cover Image: Corbis

Back cover Image: still from Playtime (1967),

Specta/The Kobal Collection

Designed by Pfisterer + Freeman

For Charlotte and Cecilia,

with me every step of the way.

THE MIEGUNYAH PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

187 Grattan Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2012

Text Gideon Haigh, 2012

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing

Limited, 2012

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Designed and typeset by Pfisterer + Freeman

Printed by Griffin Press, South Australia

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Haigh, Gideon.

The office: a hardworking history / Gideon Haigh.

9780522855562 (pbk)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Work environmentSocial aspectsHistory.

WorkPsychological aspectsHistory.

Office politicsHumor.

White collar workersHistory.

302.35

Page ii: Architect Howard Roark (Gary Cooper) beside his first

skyscraper in The Fountainhead: the world is made of glass

In the early twenty-first century, something happened to offices for the very first time. Over the course of history, they had been centralised and decentralised, systemised and mechanised, upsized and downsized, reorganised and deorganised, imported and exported, reverenced and ridiculed. At last, they became perhaps all that was left: fashionable.

As of 2007, the hottest show on American television was Mad Men, centred on a 1960s Madison Avenue advertising firm. The slickest addition to British television was The Hour, set in a 1950s BBC newsroom. Actually, offices had been providing small-screen mise en scnes for some time: from the drama of The West Wing, The Wire and Boston Legal to the comedy of Ally McBeal, The Thick of It and 30 Rock. Mad Men and The Hour backdated the custom, as if to explain to the middle-aged what their parents had been up to all those years ago.

Most obviously, there was that infinitely adaptable vehicle known in France as Le Bureau, in Brazil as Os Aspones, in Canada as La Job and in Chile as La Ofis: what had started life as the British sitcom The Office, and inspired a continuing American sitcom of the same name. Low-key, anti-escapist, sometimes darkly absurdist, The Office found exasperations and consolations among the familiar environs of workstations and partitions, both satirising and ennobling the daily grind. Even those who were not regular viewers somehow recognised the events and scenes in their office that were like The Office.

There were healthy takings for movies like The Company Men (2010), about people fired from an office, Up in the Air (2009), about people firing people from offices, Horrible Bosses (2011), about people from offices killing other people from offices, and Inside Job (2011), about people from offices killing the global economy; one already hugely successful movie franchise inspired by the best-selling spoof confessions of a single woman in a publishing office, Bridget Jones's Diary (2001), was poised to become a West End musical. The literary intelligentsia thrilled to a paean to office tedium, David Foster Wallace's The Pale King (2011). Social trendspotters nodded as that zeitgeistiest of journalists, The New Yorker's Malcolm Gladwell, called for offices to be recognised as multipliers of social capital: The reason Americans are content to bowl alone is that, increasingly, they receive all the social support they needall the serendipitous interactions that serve to make them happy and productivefrom nine to five. Political savants brooded on the decade's definition by the destruction of what had been the world's most recognisable office buildings: the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

Occurring across such a broad cultural front, this sudden wakening to the ubiquity of offices, office work and office life was perhaps less conspicuous than vogues for vampires and crazes for junior magicians. But it was more intriguing for a curious fact: that these same phenomena, for much of their history, had not been considered interesting at all.

* * * *

There is glamour to corporate and political leadership; there is force, strength and a sweaty eroticism to manual labour. But the clerk, the secretary, the middle manager, the technician have had no natural champion. The right hold the bureaucrat in contempt; the left scorn the bourgeoisie. Politicians make promises about the poor while making pacts with the wealthy. Historians and sociologists gravitate likewise to extremes, directing their scholarship at governing elites and disadvantaged minorities, in a way that the Marxist historian Arno Mayer once observed bordered on the suspicious. Could it be that social scientists are hesitant to expose the aspirations, life-style, and world-view of the social class in which so many of them originate and from which they seek to escape? he asked. Even a social scientist who went against that trend, C Wright Mills, thought office work mundane and office workers of little account: Whatever history they have had is a history without events.