This edition is published by BORODINO BOOKS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books borodinobooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Borodino Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

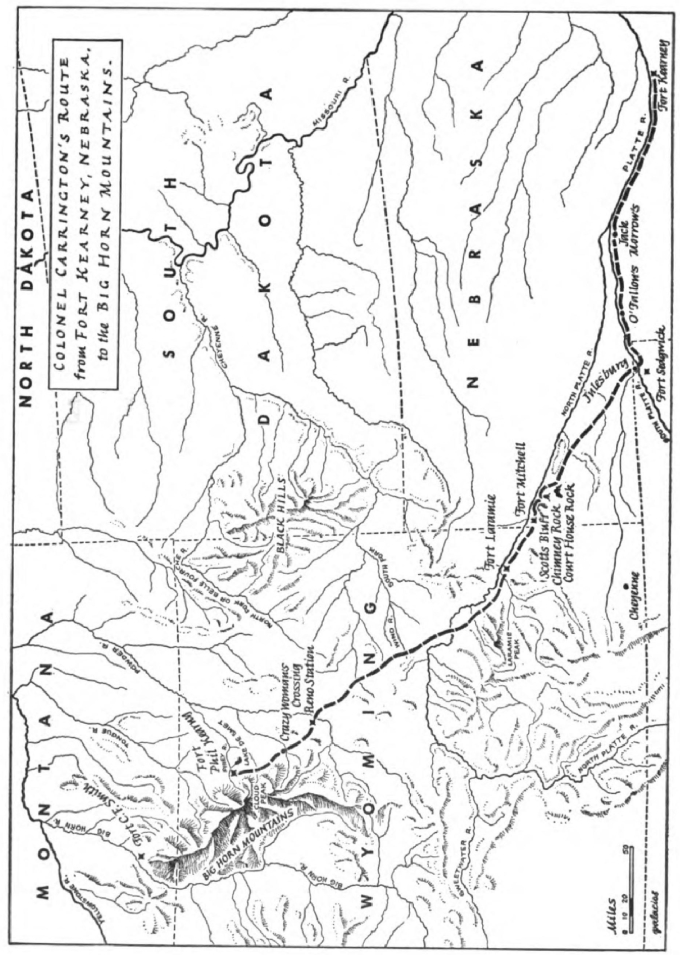

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

CARRINGTON

A NOVEL OF THE WEST

BY

MICHAEL STRAIGHT

Tragedy is an imitation, not of men as such but of an action; for life is expressed through action and its end is a way of action rather than a moral attitude.

ARISTOTLE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The events traced in these pages occurred in 1866; the characters were living then; the Orders, the dispatches, some of the speeches, and most of the letters are reproduced from the originals in the National Archives and the Indian Bureau of the Department of Interior.

The dispatches of Colonel H. B. Carrington are the primary source of the story. Further sources include: Absaraka , by Margaret Carrington; Army Life on the Plains , by Frances Carrington; the testimony taken by a Commission of Inquiry appointed by President Johnson; the records of the 40 th Congress and the 50 th Congress; the Carrington papers in the Yale University Library; the letters of Sam Gibson to Grace Hebard, in the Hebard Collection of the University of Wyoming; the dispatches of Ridgway Glover to The Philadelphia Photographer; an address by General W. H. Bisbee to the Order of Indian Wars; and an unpublished manuscript of General Frederick Phisterer, made available through the courtesy of his granddaughters.

These narratives form the outline of the story which follows. Nonetheless, it is written to be read as fiction rather than as history. For the author has not halted at the boundary of recorded events in the manner of the historian. The historian, Henry James wrote, has to say firmly to his fancy: so far thou shalt go and no further. Conrad concluded: Fiction is nearer truth.

STORY, WYOMING

On a grainfield, golden beneath the fir and snow of the Big Horns, stands the ruin of a frontier fort. Its stockade of logs sways in places, in others lies charred on the ground. The iron skeleton of a sawmill rusts among its timbers; its square nails turn up underfoot. All other traces of the fort have been erased by years of plowing; all relics of the garrison lie deeply interred. Even the log cabin built for a caretakers use is abandoned now and open to the wind and the rain. A cracked lavatory seat serves as a welcome mat in its doorway; splinters of glass from shattered windows glint on the bare floor; a broken stove swings creaking in the bedroom; there is no other sound. A dank mattress houses families of field mice through the winter. In summer they venture out on the parade ground, where meadow larks nest and the wild flax matches the sky.

Here, in July 1866, a single battalion of infantry established an outpost of the United States. Here the women of the garrison strolled on August evenings learning scenes from Shakespeare and in December watched the long wagon train return with their dead.

Today a four-lane highway cuts through the foothills, still scarred by wagon wheels. Racing along it, from the Black Hills to the Yellowstone, the traveler passes unaware of the old fort. But one mile northward a sign warns of a Historic Landmark on the ridge ahead. It is Lodge Trail Ridge: the highway slashes through it and descends along a north-running spur. There in the shadow of the ridge is the Landmark: an umber-colored finger thrust upward from gray boulders.

A pitted road leads up to the monument. The traveler parks; he steps out; he senses the wind that blows forever on the ridge. He picks his way among empty bottles, sandwich paper, comic sections from old Sunday newspapers. Leaning against the iron railing that surrounds the monument, he studies the bronze plaque fashioned in the form of a shield.

On this field on the

st day of December

1866 three

Commissioned officers

and seventy six privates

of the 18 th U.S. Infantry

and the 2 nd U.S. Cavalry and

four civilians under the

command of Captain Brevet

Lieut. Col. Wm. J Fetterman

were killed by an overwhelming

force of Sioux under the

command of Red Cloud. There

were no survivors.

No survivors. No one to tell what happened, then. The traveler glances upward and along the ridge. This officer, this Fetterman, must have come down from way up there. Why, if he was so outnumbered, did he lead his men down here where they could be surrounded? Why...The traveler shakes his head; he drives on. Between the rocks and the wind the stubborn question lingers:

Why?

1OLD FORT KEARNEY, NEBRASKA, May 18, 1866

The battalion was a unit of the regular Army. It tramped with the volunteer regiments from Vicksburg to Atlanta. And when at the wars end the volunteers headed for their homes, it tramped on, toward the Indian frontier. It made its way in winter to Fort Kearney, Nebraska. There, in March, its new Orders came:

Second Battalion, Eighteenth U.S. Infantry under Colonel Carrington will move immediately; two companies relieving the garrison at Reno Station; four companies establishing a new post on or near the Piney Fork of Powder River; two companies establishing a further outpost at or near the mouth of Rotten Grass Creek. Troops will proceed immediately so as to be able to move from Laramie on first grass. James Bridger will be employed as guide.

Troops will proceed immediately.... The ground was frozen; equipment was lacking; stores were low; many men were still disabled from the winter journey. Yet the Colonel was fired by the splendor of his assignmenthis first command in the field. He took immediately to mean as soon as possible; he worked day and night, racing against the turn of the earth.

In mid-May the first grass thrust its blades up through the crust and into the white light of the Nebraska spring. So the day came for the battalion to march on westward. The Colonel rode out with a guard of honor to greet the commander of the Western armies, come from Washington to bid old comrades Godspeed. On the parade ground of the fort the troops assembled to stand final review.

The wind, their worst enemy through the winter, surrendered on that morning. The old frame buildings of the fort looked less dilapidated in the spring shine. Stretching and sighing, stiff after months in quarters, the veterans of the Second Battalion stood at ease. The lieutenant detailed to lead the review stood motionless in front of the formation. To its right the twenty musicians of the regimental band licked the mouthpieces of their silver horns. Beyond the band the women clustered, their parasols folded, their poke bonnets tilted forward. At the edge of the parade ground a group of teamsters and laundresses and unassigned soldiers looked on. Off by itself an odd object maneuvered on five spindly legs: a photographer half hidden behind his camera, his arms circling like claws from beneath its black hood.