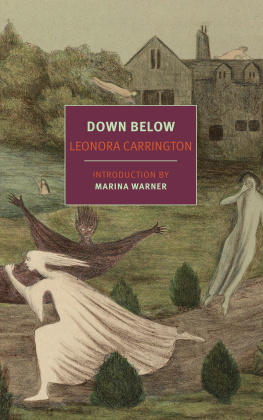

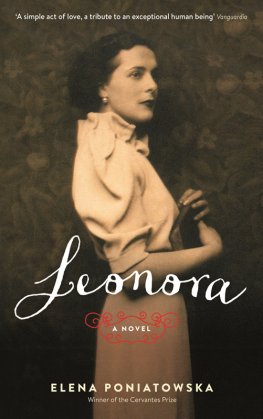

LEONORA CARRINGTON (19172011) was born in Lancashire, England, to an industrialist father and an Irish mother. She was raised on fantastical folk tales told to her by her Irish nanny at her familys estate, Crookhey Hall. Carrington would be expelled from two convent schools before enrolling in art school in Florence. In 1937, a year after her mother gave her a book on surrealist art featuring Max Ernsts work, she met the artist at a party. Not long after, Carrington and the then-married Ernst settled in the south of France, where Carrington completed her first major painting, The Inn of the Dawn Horse (Self-Portrait), in 1939. In the wake of Ernsts imprisonment by the Nazis, Carrington fled to Spain, where she suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to a mental hospital in Madrid. She eventually escaped to the Mexican embassy in Lisbon and settled first in New York and later in Mexico, where she married the photographer Imre Weisz and had two sons. Carrington spent the rest of her life in Mexico City, moving in a circle of like-minded artists that included Remedios Varo and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Among Carringtons published works is a novel, The Hearing Trumpet (1976), and two collections of short stories. A group of stories she wrote for her children, collected as The Milk of Dreams, is published by The New York Review Childrens Collection; her Complete Stories is published by Dorothy, a Publishing Project in the United States and by Silver Press in the United Kingdom.

MARINA WARNER s studies of religion, mythology, and fairy tales include Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary, From the Beast to the Blonde, and Stranger Magic (National Book Critics Circle Award for Literary Criticism; Truman Capote Prize). A Fellow of the British Academy, Warner is also a professor of English and creative writing at Birkbeck College, London. In 2015 she was given the Holberg Prize.

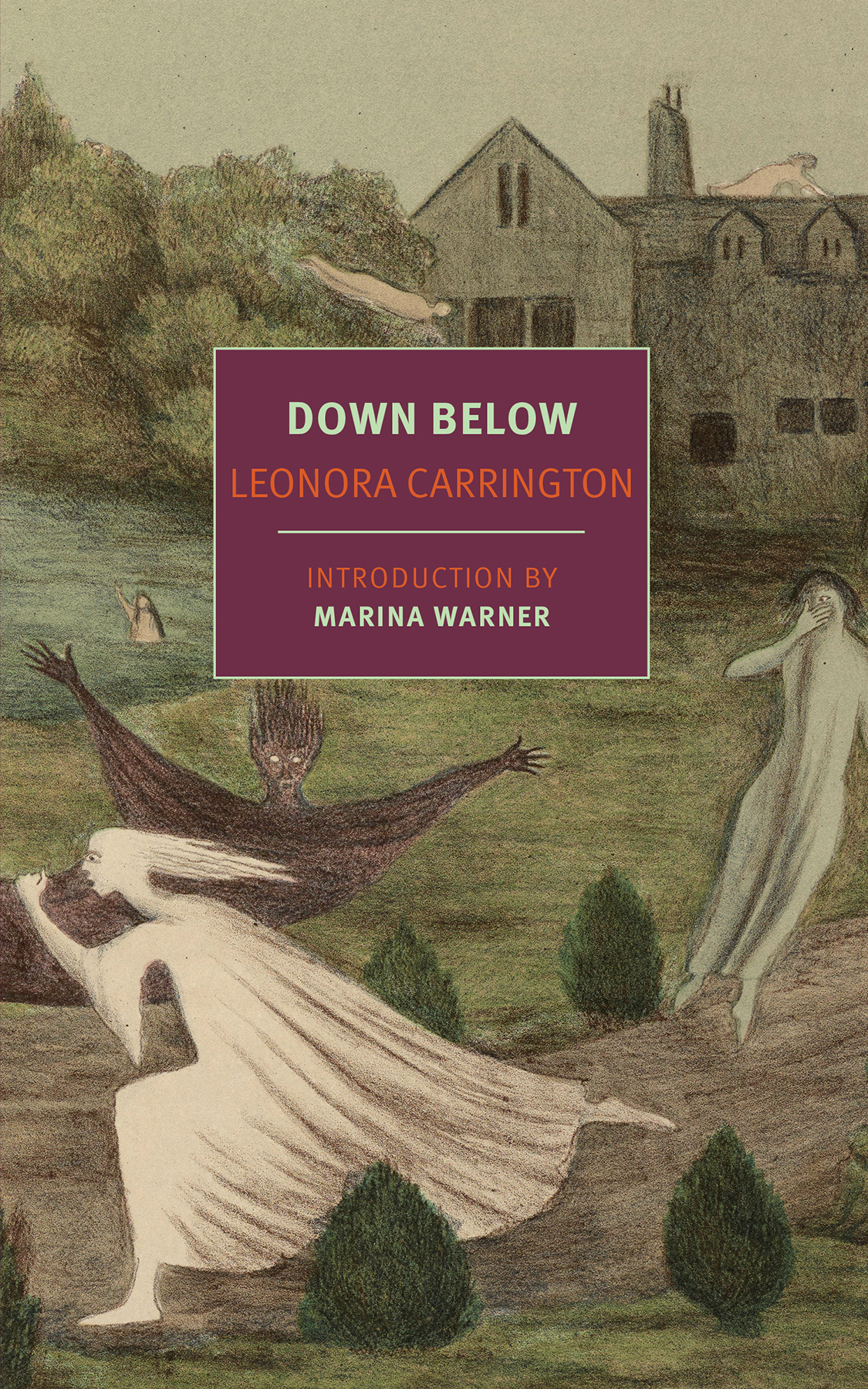

DOWN BELOW

LEONORA CARRINGTON

Introduction by

MARINA WARNER

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1988 by Leonora Carrington

Introduction copyright 2017 by Marina Warner

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Crookhey Hall, 1987; 2016 Estate of Leonora Carrington / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Princeton University Art Museum/Art Resource, NY

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Carrington, Leonora, 19172011, author.

Title: Down below / Leonora Carrington ; introduction by Marina Warner.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, 2017. | Series: NYRB Classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026859| ISBN 9781681370606 (softcover) | ISBN 9781681370613 (epub)

Subjects: | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Artists, Architects, Photographers. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women.

Classification: LCC PR6053.A6965 A6 2017 | DDC 823/.914dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026859

ISBN 978-1-68137-061-3

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T HE YOUNG Leonora Carrington was determined to leap free of the dictates of her rich industrialist family: an early self-portrait shows a white horse (a perennial alter ego) leaping out of the window behind her, while a she-hyena (another familiar, another soul-sister), her udders leaking milk, comes docilely to the artists hand. Edward James, the connoisseur and a patron of the surrealists, described Leonora, then a student artist, as a ruthless English intellectual in revolt against all the hypocrisies of her homeland. In 1936, enrolled in the Ozenfant School of Fine Arts in London, she was already exploring her inner world, the hypnagogic visions that rose before her eyes when consciousness and the unconscious merge in the in-between of waking and sleeping, and she recognized, at the first International Surrealist Exhibition in London that year, an immediate kinship with the movement. Carringtons mother had given her a copy of Herbert Reads Surrealism. There she found, reproduced in the book, Max Ernsts assemblage-painting Two Children Threatened by a Nightingale, which struck her to the heart, she said. Several decades later, she would still remember how it felt: a burning, inside; you know how when something really touches you, it feels like burning.

Max Ernst, born in 1891, has been somewhat eclipsed in the galaxy of artists of the periodArshile Gorky, Mret Oppenheim, Lee Miller, Giorgio de Chiricobut at the time he was idolized: according to Andr Breton, the despotic arbiter of the surrealist pantheon, he was the most magnificently haunted brain of our times. Ernst was Loplop, Prince of Birds, the surrealist movements Bird Superior, eclipsing all others in fame and prestige with his effortless gaiety and cruelty of invention, his unstinting ability to replenish the store of fantasies and improvise new media, new methods. He had realized the doctrine Breton had proclaimed in the first manifesto: Nimporte quel merveilleux est beau, il ny a meme que le merveilleux qui soit beau. (Anything that is marvelous is beautiful, indeed only the marvelous is beautiful.)

When Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst met, she was nineteen years old and he was forty-six; she appeared to him as if directly summoned from the surrealist dream world, fulfilling every fantasy about the femme-enfant, the child-medium who excites the lovers imagination and moves him to fresher, stronger visions. Belief in the penetrating faculty of youth, in the young woman-childs closeness to mystery and sexuality, formed the crux of surrealist doctrine. In the fictional quest story LAmour fou, published in 1937 (the same year Ernst met Carrington), Breton wrote a letter to his newborn daughter: Let me believe that you will be ready then [on her sixteenth birthday] to embody the eternal power of woman, the only power before which I have ever bowed. To Breton the femme-enfant was a figure of salvation, because in her and only her there seems to me to dwell, in a state of absolute transparency, the other prism of sight, which we stubbornly refuse to take into account, because it obeys laws which are very different, and which male despotism must prevent at all costs from being divulged. She was the marvelously magnetic conductor, the only one capable of retrieving that age of wildness. Ernst, in the autobiographical texts collected in Beyond Painting, recalled dreams teeming with such young women, and his frottages and collages conjure imaginary beings such as the nymph Echo, Perturbation, my sister, and Marceline-Marie, the little girl who dreams of entering Carmel. In the preface he wrote to the short story The House of Fear, Leonora was la marie du vent incarnate, the bride of the wind of his desire, anticipated eleven years beforehand in the suite of prints Histoire naturelle.

Almost immediately, the couple left for Paris; she was to come back to England only once more, forty years later, for the funeral of her mother.

Soon after arriving in Paris, Leonora first exhibited her paintings in a show where the original sheets of Ernsts collage novel of 1934, Une Semaine de bont (A Week of Kindness, or The Seven Capital Elements), were also displayed, showing a sweet-faced and imperturbable young protagonist endlessly subjected to floods and mayhem, fire and assault in a wickedly adroit parody of the penny-dreadful picture romance. In this suite of images, and its earlier companions,