The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To loved ones who are gone and beloved places that remain

Mama was dying.

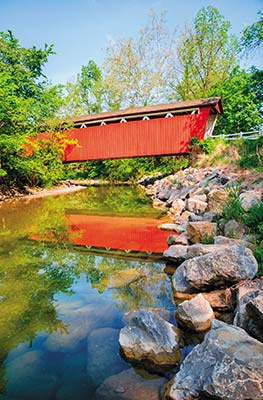

I didnt know this when I pulled off Californias Highway 101 just before the bridge crossing over the Klamath River.

We were about an hour away from our destination, a campground in Redwood National and State Parks. Temporary signs along the road had alerted drivers to be prepared for what was ahead: a whale jam.

I pulled the rental car into a dirt parking lot. My wife, daughter, and I got out and joined the people walking toward the two-lane bridge to see Mamaa forty-five-foot-long female gray whale who had entered the river in late June 2011 along with her calf.

Thousands of people had been pulling over every day, standing on the edge of the bridge, taking pictures, oohing and aahing as Mama shot air and water out of her blowhole while her calf swam by her side.

In late July, the calf returned to the ocean.

Mama stayed.

When we got there in mid-August, she still was in the river, still swimming circles under the bridge, still creating whale jams on Highway 101. But she also was drawing more concern by the day. I didnt know this at the time, but flotillas of kayaks, canoes, and stand-up paddleboards had tried to coax her out of the river and back into her natural habitat, the salt water of the ocean. Members of the Yurok tribe hopped in a small boat and tried drumming and singing. Others tried flutes, violins, and ukuleles.

Mama stayed in the river.

Scientists tried fear, playing recordings of killer whales farther upriver, hoping the sound of a predator would make Mama head back to the ocean.

Mama stayed in the river, swimming her circles under the bridge.

When we arrived, it was an overcast day, the sky almost as gray as the whale.

We walked onto the bridge, sticking close to the railing on the left to stay out of the way of the traffic coming from the north. My daughter, Mia, spotted Mama first. She hurried to get out her camera and turn it on, worried that she was going to miss the shot.

Mia was nine. The camera had been a Christmas gift the previous year.

When I was her age, I had a Kodak Hawkeye Flashfun II. I loved photography for the same reason I loved baseball. Because Dad did. When we made family trips, Dad and I both brought our cameras. When I grew up, I wanted to be Ansel Adams, play shortstop for the Detroit Tigers, and go to the moon. So I suppose giving Mia a camera was another example of parents trying to re-create their own childhood. And as with many such attempts, it hadnt worked as hoped. Mia hadnt used her camera much.

But now she seemed intent on getting a shot of Mama. Not that she needed to worry about Mama suddenly heading off to sea. The whale didnt get far from the bridge before she turned around and swam back toward us. When she passed under the bridge, the crowd shifted to the other side. Back and forth, back and forth.

On one pass, Mia took a picture, glanced at the back of her camera, and said, Look!

I explained that once upon a time, back when there was something called film inside cameras, we didnt know until long after the trip whether we had captured the moment. She didnt roll her eyes. We were making progress.

Mia had been complaining nonstop ever since we left our home in Jacksonville, Florida, flying to San Francisco and heading north. She didnt care if we were going to a national park. She didnt want to be doing a long drive or camping or pretty much anything else I had planned. She wanted to be at home, sleeping in her own bed, watching her familiar TV shows, enjoying the final week of summer before school started again.

I dont want to go, she said repeatedly, as though if she said it often enough we might change our minds and head back to Florida.

The only time she wasnt complaining, she was watching movies. As I drove north, there was one point, as the redwoods seemed to be growing taller by the minute, that I tried to point out the trees. I got no response. Mia was busy watching Rio . My wife, Toni, was checking something on her iPhone.

I was frustrated and annoyed. Pissed off at the electronic devices. Pissed off that this wasnt turning out like I had envisionedwhich is to say, a remake of the trip I made to the redwoods when I was nine years old.

* * *

MOST OF THE details from childhood are hazy and jumbled. Many are gone completely. Ive tried to recall specific Christmas and birthday gifts. Other than the Kodak camera and a red baseball glove, I just come up with vague memories of sweaters, model rockets, and vinyl albums.

This isnt simply because my parents didnt give us extravagant gifts. Although in a monetary sense, that certainly was true. During my childhood, Dad was a missionary on an Indian reservation in Nevada, a minister at a couple of midwestern churches, and a chaplain at a hospital. Mom stayed at home to raise three children, then got her masters and became a social worker andmuch to my chagrin when she showed up in my high schoola substitute teacher.

But even on their limited income, my parents managed to give us some epic family trips.

Before our trips I would ride my bike with the banana seat to a nearby Shell station and get mapsactual folded paper mapsso I could plot out the route. I remember being excited whenever we spotted a sign saying that we were entering a new state. But the most magical of signsbrown, with an arrowhead logo, snowcapped mountains, a bison and a sequoia treeannounced that we were entering a national park.

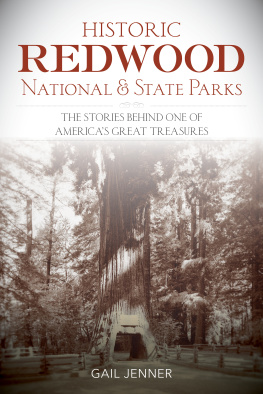

We went to Yosemite, Lassen, Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, and later, on a trip to the East Coast, a series of historical sites from Philadelphia to Washington. The years have jumbled the timeline a bit. But I think my first national park was at that time, in the late 1960s, one of Americas newest national parks: Redwood National and State Parks.

More than forty years later, I could close my eyes and imagine our campsite. Not only could I picture the pop-up camper that we pulled behind the station wagon, but I could hear it being set upa mix of metal rails sliding, canvas popping open, and Dads swearing. Whenever I watch A Christmas Story and hear Ralphies dad fighting with the malfunctioning furnace, I think of my dad and the camper.

It slept four, room enough for my parents and my two sisters. I set up my pup tent maybe twenty feet away. I was closer to my parents there than I was in my bedroom at home. And yet being in that tent was liberating, frightening, and exciting.

The tent was made of thick canvas, a material that when it rained seemed to do a better job at soaking up water than repelling it.

Id fall asleep to the sounds of the woods. Rustling trees, snaps of branches. Id wake up to birds chirping, pots and pans clanging, the poof of the camp stove, and the sizzle of breakfast.

I remember walking back to the campsite after ranger talks, shining a flashlight into the trees, turning it off, and getting a glimpse of so many stars that it made the planetarium at home suddenly seem understated.

I remember the smell of the redwoods.

I didnt realize just how deeply this scent was embedded until we got out of the rental car at the bridge over the Klamath River and I took a deep breath.