Credits for previous publications included in this work

appear on pages 31517, which constitute an

extension of this copyright page.

2019 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Designed by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Set in 10.25/13.5 Miller Text by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed digitally

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Atwood, Nancy C., 1933 editor. | Atwood, Roger, editor.

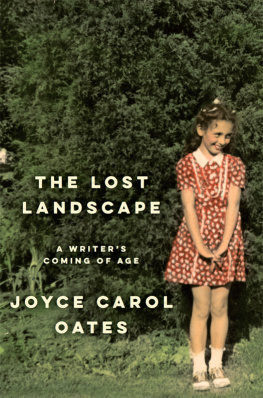

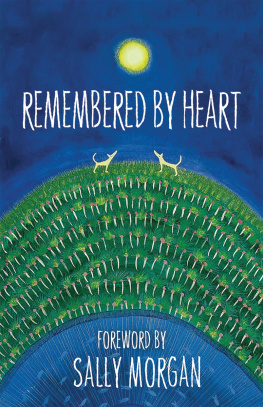

Title: Coming of age in a hardscrabble world : a memoir anthology / edited by Nancy C. Atwood and Roger Atwood.

Description: Athens : The University of Georgia Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018057734| ISBN 9780820356655 (hardcover. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820355320 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780820355337 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Working class writings, American. | Working classLiterary collections. | American literature20th century. | American literature21st century.

Classification: LCC PS508.W73 C76 2019 | DDC 810.8/09220623dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018057734

acknowledgments

We thank Bethany Snead, our acquisitions editor at the University of Georgia Press, whose response to an initial email query in 2017 conveyed enthusiasm, so appreciated then and still appreciated now, as it has taken the form of solid, trustworthy support for the preparation of our book.

Nancy: I had been reading memoirs for years, when I first realized that the books I read for fun were also a valuable resource for serious readers and human-service professionals like me. I had just finished reading a memoir by Fred Allen, a favorite radio and TV comedian from my youth and was sitting in the great reading room of the Boston Public Library waiting for the delivery of a book I had requested. A teenage boy deposited the book on the table in front of me, and that reminded me of Allen. As a poor boy in Boston Allen had an after-school job finding books in the stacks and delivering them to patrons. I knew that because I read about it in his memoir. That was a curiously compelling moment for me: readers can find out about the lives of others by reading memoirs. Once I realized the obviousthat memoirs are a source of information about lifeI began studying them in earnest and organizing what I found into articles that I wanted to share with other readers. Members of my family were willing to read drafts, and Gwendolyn, Christopher, and Claire Atwood were characteristically perceptive in their comments. My former employer, Smith College School for Social Work, published my first work based on memoirs, Experiencing Inequality: Memoirs, Hardship, and Working-Class Roots, in the fall 2014 issue of its journal. Importantly, to my delight, my oldest son, Roger, a writer-journalist, agreed to become coeditor of the anthology that I was planning as an outgrowth of that article. Throughout the process of working with him I have deeply appreciated the insights, writing skills, and hard work he has brought to the project.

I have consulted with others to help to shape the memoirs into an anthology especially suitable for college and university students. Two are English professors. Julia Prewitt Brown at Boston University guided me on how to place the memoirs within the context of other coming-of-age literature and to appreciate redemption as a key concept in both literature and psychology. Josh Cohen at Massachusetts College of Art and Design recognized how ethnic and socioeconomic diversity among memoirists can be a helpful source of identification for college students who are learning how to write personal essays. Professor of psychology Ellen Winner at Boston College had a deep appreciation for the talent of the memoirists and for the resilience they needed to succeed. Writer and memoirist Judith Nies validated differences in social class as a neglected and needed focus in narrative nonfiction. Personal essayist and former English teacher Janet Banks suggested sensible improvements in how to organize and present our material. Ernest Gonzales, professor of social work at New York University, confirmed my hunch that social-work students could learn from our anthology and urged us to add provocative questions to stimulate discussion. Lynne Benson drew on her experience teaching at a community college and public university in Boston to inspire a new conceptualization of the term social class, one that avoids labeling and dry abstraction. Brandeis University professor emerita Janet Zollinger Giele raised my feminist consciousness once again when she critiqued an early version of the book. I was blessed that Jill Ker Conway (19342018) encouraged the early development of our anthology. I wish she were alive to see how helpful her ideas were to understanding the value of our readings. The first person, besides myself and Roger, to read every single word of the memoir excerpts and comment on them in person was Henry Shull, a researcher at the Radcliffe-Harvard Schlesinger Library. He found the readings interesting and made thoughtful remarks about the effects of economic pressures on young people. I also welcomed a collective response to the memoirs from the members of my Unitarian Universalist (UU) church. The audience at First Church in Boston was attentive to my talk called Memoir from A to Z (A being Angelou and Z being Zinn). Being typical UU parishioners, they had many comments and questions. I knew from their response that the topic of memoir is a crowd-pleaser.

Roger: Nancy had been sharing her enthusiasm for memoirs with me for years before she decided to turn her passion into a book. I assisted her with the early edits, proposals, and lists of titles to include. But it was not until 2016 that I really understood the need for an anthology of memoirs by writers from working families and agreed to join Nancy in this project as coeditor. That was the year I taught a class in memoirs as an adjunct professor in the English department at the University of the District of Columbia, the public university of the city of Washington. Although we read mostly non-American writers in that class, I was struck by how my students, nearly all from working-class backgrounds and a few hoping to embark on writing careers, hungered to read true stories that mirrored their own upbringings and lives as young adults. When we read passages by Brent Staples (included in this anthology), for example, my students came alive with that same passion that I had seen over so many years in my mother, that realization that memoir, when done well, can be a uniquely honest and brave inquiry into human feeling and experience. I am grateful to UDC for hiring me and particularly professors Matt Petti, Wynn Yarbrough, and Alex Howe.

Like all independent writers, I rely on a network of friends, colleagues, and editors for feedback on ideas, intellectual companionship, and occasionally a sympathetic ear. My thanks to Fred Thys, Sam Fromartz, Sonya Hepinstall, Steve Rasin, Rupert Shortt, Jarrett Lobell, Erik Ching, Riordan Roett, Ramn Borges-Mndez, Vincent Garay, Martin Oliver, Robert Berry, and Alejandro Cedeo for their support during the years when I was working on this project. My husband, Werner Romero, as always, was there through it all with his good sense, great cooking, and endless patience.