TO THE GROUND STAFF OF THE R.A.F., WITHOUT WHOSE

ESSENTIAL WORK THE BATTLE OF THE AIR COULD

NEVER BE FOUGHT

Published by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London

SW11 6SS

Copyright Grub Street 2010

Copyright text Wing Commander Ian Gleed DFC 1942

Copyright foreword Flt Lt John Strachey 1942

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

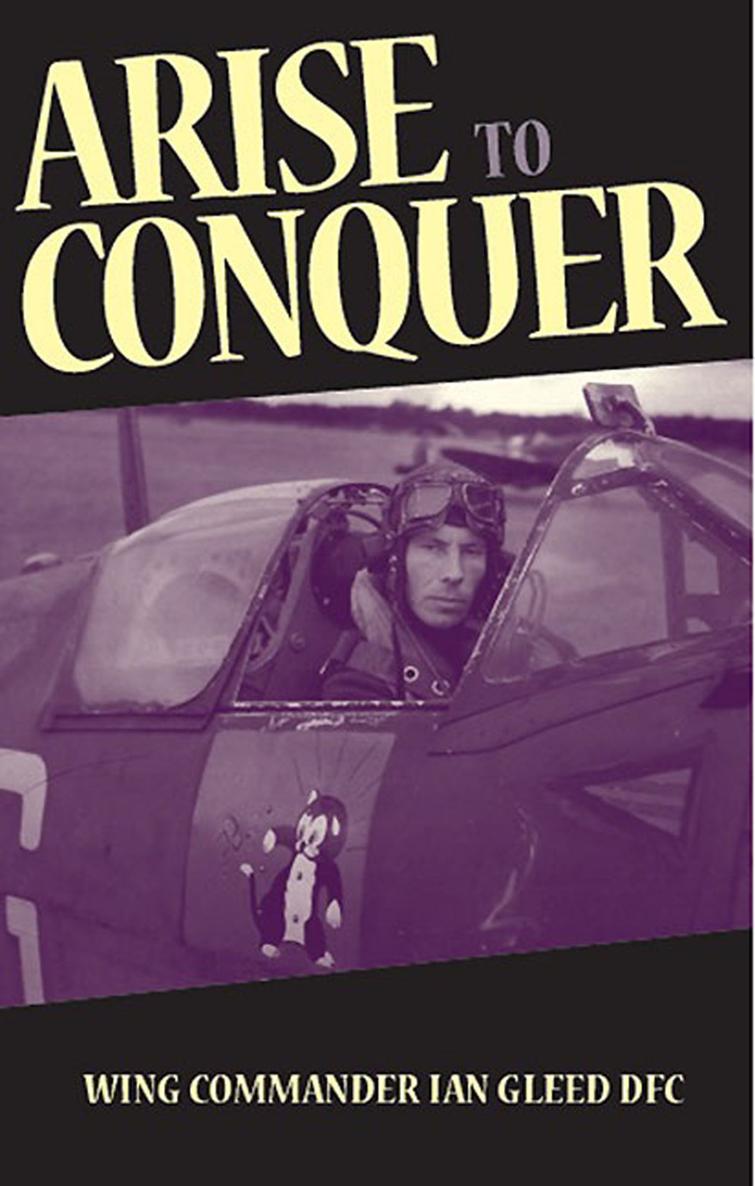

Gleed, Ian.

Arise to conquer.

1. Gleed, Ian. 2. Great Britain. Royal Air Force-

History--World War, 1939-1945. 3. World War, 1939-1945-

Personal narratives, British. 4. World War, 1939-1945-

Aerial operations, British.

I. title

940.5'44941'092-dc22

ISBN-13: 9781906502935

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-90811781-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the

prior permission of the copyright owner.

Cover design and typesetting by Sarah Driver

Printed and bound by MPG Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall

Grub street Publishing only uses FSC (Forest Stewardship Council)

paper for its books.

Publishers Note: This new edition has been reproduced faithfully and

exactly according to the first edition of 1942, with the addition only of

three new photographs courtesy of Norman franks.

The author was shot down and killed on 16th april 1943, having also

received the D.S.O.

Foreword

by Flight Lieutenant John Strachey

I t is a privilege to have the opportunity to contribute a foreword to this book by wing Commander Gleed, under whom I had the honour to serve during the greater part of 1941. In these pages the reader will find, not so much described as vividly reflected, the authentic atmosphere of the life of a fighter squadron of the Royal Air force.

He will find one of the first accounts of the Battle of Britain set down by a pilot who took part in that extraordinary engagement. It is already clear that the Battle of Britain must ever remain one of the decisive engagements in world history. however long this second world war lasts, however gigantic, portentous and over-whelming its developments may be, the series of air engage ments which took place over the eastern and southern parts of Britain between August and November 1940 must remain its first turning-point. They played, in much more desperate circumstances, the same rle as was played by the Battle of the marne in the first world war. The repulse of the air attack on Britain did not mean (by how many years, how many million deaths, how many prodigious events, we do not yet know) that the Fascist attempt to conquer the world had failed. On the contrary, the point at issue was that that attempt must have succeeded if the Battle of Britain had been lost. If the tiny number of British fighter squadrons which were at that time air-worthy had then been overborne, none of the rest of the gathering of forces which will at last be adequate to the defeat of Nazi Germany and her Allies; neither the subsequent British recovery; nor the Russian resistance; nor the American entry into the war, could have taken place. The disproportion between the illimitable stake and the minute force involved is breath-taking.

I cannot but suppose that both the contemporary reader and the future historian will turn to this book when they wish to know what the pilots who did this thing were like. For it seems to me that once they have read it they will know. They are here depicted with an artlessness which the most experienced authors will profoundly envy: watty, eternally making his model aeroplanes in the dispersal huts (he is making them still, just about able, on the latest information, by unremitting toil to keep pace with his crashes); the resilient, the irrepressible Rubber (he has just had to bale out again); Robbie, with his affectation of extreme disinterest in the war and his off-hand charm (he is in a new job now); and the author himself, whom the reader will get to know best of all.

These, and just a few hundred more, were the pilots who did it. It was they who, when the telephone bells rang in the dispersal hutswhen Ops. said, One hundred plus; or a hundred and fifty plus; or two hundred plusare crossing the coast, jumped into their cockpits, took off and fought till the German aircraft turned back. In so doing, they settled the kind of lives which all of us, and our children, and probably their children, will lead.

we are bound to feel an insatiable curiosity as to what they were like, how they felt while they were doing it, and why they did it. wing Commander gleed, without for one moment trying to do so, answers these questions.

The simplest, and in my view the most exciting, thing which emerges is the fact that they felt frightened. That, if you come to think of it, is their ultimate claim to glory. If they had been Nazi or japanese robots, mentally conditioned by some process of mass intoxication, some loathsome but effective scheme of mental mutilation, by which they had been dehumanised, hypnotised into actually liking death and destruction for the sake of some fhrer, then the whole thing would have been incomparably less remarkable, and incomparably less worth while. But in fact, as the reader will see, they were, and are, just young Englishmen with the same likes, dislikes, hopes, fears and expectations as the rest of their generation. They were, and are, profoundly capable of the normal, constructive pursuits of peaceful existence; they are not one jot dehumanised or brutalised; they remain intensely individual, intensely themselves; and, nevertheless, they were able to do what they did. They are still doing it.

List of illustrations in the plate section

(Drawing by Flight Lieutenant Frost)

(Drawing by Flight Lieutenant Frost)

(Drawing by Flight Lieutenant Frost)

The Start

T hat morning the batman woke me with his usual smile. Seven-thirty, and a nice morning, sir. It was September 3rd, 1939. I was twentythree. I turned on the wireless and listened to some music from Paris. After a few moments I heard Billy next door starting his french lessons on the gramophone, and at the end of the corridor micky was singing in the bath.

we all met at breakfast, some of us laughing and joking, others with hangovers, sullen and silent. Pat, the Flight Commander, was one of the latter. he told us to buck up, for we were all to be at readiness at eight-thirty, and had to taxi the machines form the hangars to dispersal positions.

Micky, Pat and I drove the boys to the hangars. We clambered into our Hurricanes. There were shouts of All clear! and Contact! All the engines started except Dimmy Simmonds: his prop was winding round with great streaks of flame pouring from the exhausts. We taxied slowly round the hangars, up the gentle grass slope, dodging the rough parts, lined the planes up along the hedge, switched off and wandered along to the recently put-up marquee.

What were you doing last night, Pat? Out with a Popsie?Yes, and I didnt get in till three, and I feel like death. Where the devil is Simmonds? Lets wander over and get the cars.

When we reached the hangar we found that Dimmys plane was unserviceable with a dud magneto. More bad language from Pat. How many does that leave us? Five in B Flight and six in A?