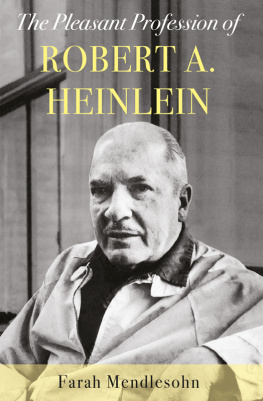

Also by the author

Fiction

Spring Flowering

Non-fiction

Childrens Fantasy Literature: An Introduction (with Michael M. Levy)

A Short History of Fantasy (with Edward James)

The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature (ed. with Edward James)

The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Childrens and Teens Science Fiction

On Joanna Russ

Rhetorics of Fantasy

Foundation 100 (ed. with Graham Sleight)

Diana Wynne Jones: Childrens Literature and the Fantastic Tradition

Glorifying Terrorism: An Anthology of Science Fiction Stories

Polder: A Festschrift in Honour of John Clute and Judith Clute

The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction (ed. with Edward James)

The True Knowledge of Ken MacLeod (ed. with Andrew M. Butler)

Quaker Relief in the Spanish Civil War

Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature (ed. with Andrew M. Butler, Edward James)

The Parliament of Dreams: Conferring on Babylon 5 (ed. with Edward James)

Edited by Edward James

This book owes a few debts.

To George Slusser, who suggested to a first-year Ph.D. student in 1993 that she should write a book on Heinlein.

To Edward James, who, when twenty years later that ex-Ph.D. student was pondering the open invitation from Illinois, reminded her of this.

To Bill Patterson, whose biography of Heinlein has rendered this project ever so much more feasible.

To the fans who have made my life so much easier with online concordances.

And finally

To everyone who makes science fiction and its communities.

Contents

Preface

The origins of this book lie at the very beginning of my career. I began reading science fiction in the 1980s, with a suitcase full of books given to me by my fathers best friend. I quickly found more of Heinleins juvenile novels in the library. In 1988, as a second-year undergraduate, my tutor persuaded me that instead of writing on the history of romance I should take a look at the history of science fiction. His was not an entirely disinterested position: he had recently become involved with the Science Fiction Foundation, had through that organisation aided the establishment of the Arthur C. Clarke Award and become one of the first judges, and had also become the editor of Foundation: the International Review of Science Fiction. When I walked through his door in October 1986, noted his bookshelves and said, Oh, you read science fiction?, I suspect my dissertation fate was sealed. In 1988 I accepted his suggestion and embarked on a study of six science-fiction writers over a twenty-year period (19651985), considering how their portrayal of women had shifted and changed. This was a fairly standard approach to material at the time. As I was in a history department, Marxist social and cultural theory had far more influence than any interest in literary quality, and as those who know my work will recognise, this has barely shifted in almost thirty years. I have always been interested in the typical rather than the ground-breaking, in a body of work rather than single texts.

The effect of this approach was to produce a different outcome and assessment than a literary scholar might expect. Because of the nature of the study I needed a set of people who had written continuously across the period I had chosen: for the women, I selected Ursula K. Le Guin, Marion Zimmer Bradley and James Tiptree, Jr. (I would have liked to include Joanna Russ, but she was not prolific enough); for the men I chose Harry Harrison, Samuel R. Delany and Robert A. Heinlein.

At the end of the study (an abbreviated version of which can be read in Foundation 53, Autumn 1991) I had reached an unexpected conclusion. Of the six authors considered, five showed very little change in their attitudes: whether radical (Delany) or liberal (Bradley), where they began was more or less where they ended. The exception was Heinlein. Over a period of twenty years, Heinleins attitudes had shifted noticeably. Were one to include the twenty years previous to that, the word would be dramatically. This was not always (from my 1980s feminist point of view) a good shift, but it was there, and I was fascinated. Here was a person sometimes ahead of his time, sometimes crosswise, and, towards the end, in retrenchment. As a historian how could I not be entranced? I have never lost my love of Heinleins work. Because I am not strictly a literary critic, it bothers me not one bit that he is not the greatest of stylists (although the playfulness and serviceability of Heinleins prose is often overlooked).

It is not terribly clear how much more influential Heinlein will become. The critical voices are getting louder, and although as a historian I frequently want critics to have a stronger sense of context (as I note in Chapter 7, Heinleins most controversial comment on slavery is actually a quote from Booker T. Washington) we live now, in our context, and what was radical once we can recognise as problematic, and something to be argued against. For all I value Heinlein I do not require him to continue to be read or valued as contemporary fiction. Because I am a historian, discussing the really terrible Heinlein works can be enfolded into a discussion of his limitations (both rhetorical and political) and understood without serving as some kind of justification. As a historian, I am perfectly happy to know that I like Heinlein without feeling that it is essential that newcomers to science fiction need to read him. I like 1930s pulp magazines as well and I wouldnt wish those on any but the most serious of historians.

The purpose of this book is to tease out what I find fascinating about Heinlein, good, bad and reprehensible, and to understand his work as a close-to-fifty-year-long argument with himself and those he admired.

NB. In what follows, since I am aware that there are many editions of most of these novels, I have cited quotations by chapter number. I have assumed that people do not need page references to the short stories or articles.

Introduction

When Robert A. Heinlein was

Heinleins very earliest contribution to this field, Life-line, mimicked the earlier narratologies: an inventor announces an invention that threatens to rupture industrial peace, and is quietly disposed of, if only by fate. His stories The Roads Must Roll and Blowups Happen take the conventional focalising view of a journalist or anthropologist. Quite quickly, however, Heinlein began to shift the nature of the field. A key change was in his insistence that the consequence of change was more interesting than the change itself. In stories such as The Roads Must Roll, Misfit and Coventry we are introduced to the changes in the world long after they have taken place. The stories are about the psychological and social effect on human beings. Heinlein helped to move the field away from stories about the future to stories set in the future.

Heinlein produced twenty-nine stories before his engagement in the war, and another thirty-two between 1946 and 1962. He wrote thirty-one novels in total, of which thirteen are usually listed as juveniles (I will be suggesting that we might add at least two more titles to the list). Add in all the essays and collections (which often contain interesting contextual reading) and there are 129 titles.

Heinlein brought to his writing a number of sensibilities and positions. He was the middle child of a middle-class but not wealthy mid-western family; he had entered the navy to get an education and had enjoyed both the process of education and the absorption into a larger body. He brought to his writing the interest in and knowledge of engineering that gave his early stories such heft: Robert W. Bly cites Heinleins technological engagement with the invention of atomic bombs, computers, dimensional theory, exoskeletons, generational space ships, genetic engineering, hyperspace, longevity studies, space, asteroid mining, mutation, nuclear warfare, suspended animation and time travel. Heinleins work, particularly everything before 1960, is a part of what Paul Boyer in his book By the Bombs Early Light , calls Fantasies of a Techno-Atomic Utopia (p. 107) in which atomic power could fuel cars, change the polar ice coverage (melt it for a warmer climate, without worrying about polar bears), control the weather and generally perform miracles (pp. 107122). Heinlein was never really a hard SF writer: he was always more interested in the human than the machine, more interested in the use of invention than the invention itself. Peter Nicholls, in his essay Robert A. Heinlein, in Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies , offers an accurate assessment when he maintains that the emotional centre of his work has always been the political and social satire of man, and the cultures he builds and lives in (p. 63). Alfred Berger, in his book The Magic that Works , argues persuasively that it is in this way that Heinlein contributed to the feel that there was a science of society (p. 91).

Next page