ROBERT A. HEINLEIN

IN DIALOGUE WITH HIS CENTURY

ROBERT A. HEINLEIN

IN DIALOGUE WITH HIS CENTURY

19071948

LEARNING CURVE

WILLIAM H. PATTERSON, JR.

WILLIAM H. PATTERSON, JR.

TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES BOOK NEW YORK

ROBERT A. HEINLEIN: IN DIALOGUE WITH HIS CENTURY: VOLUME 1, 19071948: LEARNING CURVE

Copyright 2010 by William H. Patterson, Jr.

All rights reserved.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

www.tor-forge.com

Tor is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Patterson, William H., 1951

Robert A. Heinlein / William H. Patterson.1st ed.

p. cm.

A Tom Doherty Associates book.

Includes bibliographical references.

Contents: v. 1. 19071948, learning curve

ISBN 978-0-7653-1960-9

1. Heinlein, Robert A. (Robert Anson), 19071988. 2. Heinlein, Robert A. (Robert Anson), 19071988Political and social views.

3. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 4. Science fictionAuthorship. I. Title.

PS3515.E288Z82 2010

813'.54dc22

[B]

2009041202

First Edition: August 2010

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To be overwise is to ossify; and the scruple-monger ends by standing stock-still. Now the man who has his heart on his sleeve, and a good whirling weathercock of a brain, who reckons his life as a thing to be dashingly used and cheerfully hazarded... keeps all his pulses going true and fast, and gathers impetus as he runs, until, if he be running towards anything better than wildfire, he may shoot up and become a constellation in the end.... Every heart that has beat strong and cheerfully has left a hopeful impulse behind it in the world, and bettered the tradition of mankind.... The noise of mallet and chisel is scarcely quenched, the trumpets are hardly done blowing, when, trailing with him clouds of glory, this happy-starred, full-blooded spirit shoots into the spiritual land.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, Aes Triplex

CONTENTS

ROBERT A. HEINLEIN

IN DIALOGUE WITH HIS CENTURY

INTRODUCTION

What were you doing when... ?

Life-defining events come in all sizes. Everyone experiences the big, public ones together:

- the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Bobby Kennedy

- the first Moon landing

- the Challenger disaster

- the morning of September 11, 2001.

The small-scale, personal events are shared by ones and twos:

- your first kiss and the song that was playing on the radio, your first dance

- the day your father or mother died.

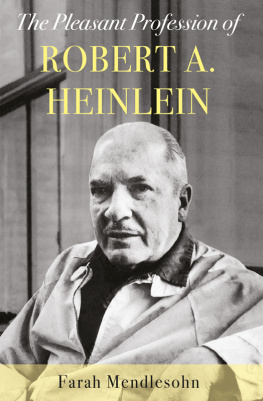

For hundreds of thousands of people around the world, Sunday afternoon, May 8, 1988, was one of those life-defining moments. Phone trees formed spontaneously, friend calling friend: Have you heard the news? Robert Anson Heinlein died that morning.

The wake of grief widened and circled the globe several times that day, as it had when Mark Twain diedto Germany, and to France and to Italy. On it went, to Yugoslavia (a country itself now gone) and to the Soviet Union, to Shanghai and on to Japan; north, to Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and south where the scientists at McMurdo Sound in the Antarctic had gathered around him a few years before, to shake his hand.

Heinleins hard-core un-common sense, dosed out mostly as entertainment, had given the parentless generations of the mid-twentieth century something of what previous generations had gotten, in quiet moments one-on-one with their fathers and their tribes wise men: their portion, all they could take, of life wisdom. They counted Heinlein their intellectual father, as an earlier generation regarded Mark Twain, and now his boysand girlswere grown to responsible maturity, hands on the tiller. They had needed, sometimes desperately, to hear what he had to saynot slogans, but tools:

What are the facts? Again and again and againwhat are the

facts? Shun wishful thinking, ignore divine revelation, forget what the stars foretell, avoid opinion, care not what the neighbors think, never mind the unguessable verdict of historywhat are the facts, and to how many decimal places? You pilot always into an unknown future; facts are your single clue.

The story of Robert A. Heinlein is the story of America in the twentieth century, and the issues he concerned himself withand the methods by which he grappled with themwere cutting-edge for his time. When Heinlein began writing, science fiction was in a struggle to lift itself and its readers out of Victorian notions, and he was immediately recognized as a leader in that Modernist struggle. After World War II he took on propaganda purposes, as he styled them, that required him to reframe science fiction again, to talk, not just to excited genre readers and editors, but to the general public, who could use the intellectual tools science fiction had created before the war to grasp and manage their increasingly technology-dominated future.

It is a truism of literature that the prestige forms of one era grow out of the subliterary forms of a prior era, and Heinleins writing career spans the transformation of a subliterary pulp genre into a significant dialogue partner at the interface of science and public policya transformation for which he is in no small degree responsible.

Like his mentors, H. G. Wells and Mark Twain, Heinlein became a public moralist, sure that what his readers really needed to know was how the world actually workeddangerous knowledge and subversive, especially in his influential novels for young readers.

Robert A. Heinlein was not a public figure in the usual sense: he had won peoples hearts and minds on a retail basis, one by one, in the close community of a reader and a book.

What he meant to his readers grew slowly over the years. The nervous teenager who stood in the shade of the Gate House of the United States Naval Academy and took the midshipmans oath on June 16, 1925, was a rustic by the standards of the society he was moving into, all raw potential.

In 1947 he became a public figure when he pioneered science fiction into

And twenty years later, Heinlein sat in a makeshift CBS studio in Downey, California. It was July 20, 1969, and Eagle had landed. Walter Cronkite and Arthur C. Clarke were talking heads on the studio monitor... and they wanted him there for commentary, when he was too excited, almost, to talk at all.

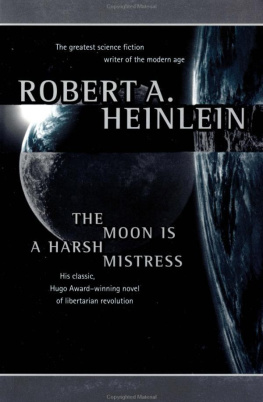

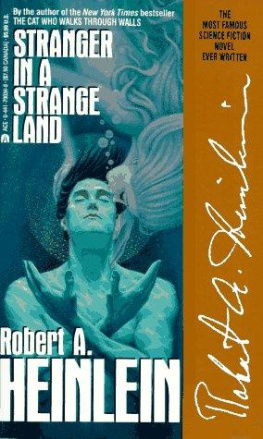

Heinlein had yearned for the Moon for most of his life, and he had done what he could to make it happenin aeronautical engineering in the Navy, then writing about it, making it real to readers after the Navy chewed him up and spit him out in 1934. Destination Moon was released in 1950 and caused a national sensation by visualizing for the people of the world the first trip to the Moon. Heinlein got on with his real work, teaching people how to live in the future. Now, in 1969, he was a celebrity again, his big satire on hypocrisy, Stranger in a Strange Land, still picking up steam, though almost nobody seemed to understand it was not a book of answers, but a book of questions.

Heinlein grew up in the horse-and-buggy Midwest of Kansas City. He lived through the Jazz Age and the tearing poverty of the Great Depression. He churned out bucketfuls of pulp, and this is where it brought him. He had hit it almost on the dot: his fictional lunar landing in The Man Who Sold the Moon was set in 1970, and it was happening only five months early.

Next page

WILLIAM H. PATTERSON, JR.

WILLIAM H. PATTERSON, JR.