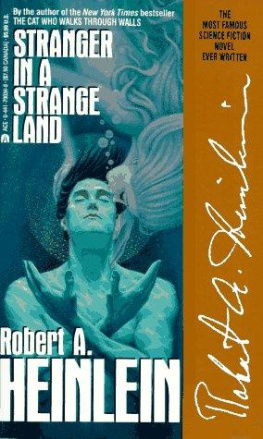

Robert A. Heinlein

Stranger in a Strange Land

For

Robert Cornog

Fredric Brown

Phillip Jose Farmer

NOTICE

All men, gods; and planets in this story are imaginary.

Any coincidence of names is regretted.

R.A.H.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Part One

His Maculate Origin

ONCE UPON a time there was a Martian named Valentine Michael Smith.

The first human expedition to Mars was selected on the theory that the greatest danger to man was man himself. At that time, eight Terran years after the founding of the first human colony on Luna, an interplanetary trip made by humans had to be made in free-fall orbits from Terra to Mars, two hundred-fifty-eight Terran days, the same for return, plus four hundred fifty-five days waiting at Mars while the planets crawled back into positions for the return orbit.

Only by refueling at a space station could the Envoy make the trip. Once at Mars she might return if she did not crash, if water could be found to fill her reaction tanks, if a thousand things did not go wrong.

Eight humans, crowded together for almost three Terran years, had better get along much better than humans usually did. An all-male crew was vetoed as unhealthy and unstable. Four married couples was considered optimum, if necessary specialties could be found in such combination.

The University of Edinburgh, prime contractor, sub-contracted crew selection to the Institute for Social Studies. After discarding volunteers useless through age, health, mentality, training, or temperament, the Institute had nine thousand likely candidates. The skills needed were astrogator, medical doctor, cook, machinist, ship's commander, semantician, chemical engineer, electronics engineer, physicist, geologist, biochemist, biologist, atomics engineer, photographer, hydroponicist, rocketry engineer. There were hundreds of combinations of eight volunteers possessing these skills; there turned up three such combinations of married couples but in all three cases the psycho-dynamicists who evaluated factors for compatibility threw up their hands in horror. The prime contractor suggested lowering the compatibility figure-of-merit; the Institute offered to return its one dollar fee.

The machines continued to review data changing through deaths, withdrawals, new volunteers. Captain Michael Brant, M.S., Cmdr. D. F. Reserve, pilot and veteran at thirty of the Moon run, had an inside track at the Institute, someone who looked up for him names of single female volunteers who might (with him) complete a crew, then paired his name with these to run problems through the machines to determine whether a combination would be acceptable. This resulted in his jetting to Australia and proposing marriage to Doctor Winifred Coburn, a spinster nine years his senior.

Lights blinked, cards popped out, a crew had been found:

Captain Michael Brant, commanding pilot, astrogator, relief cook, relief photographer, rocketry engineer;

Dr. Winifred Coburn Brant, forty-one, semantician, practical nurse, stores officer, historian;

Mr. Francis X. Seeney, twenty-eight, executive officer, second pilot, astrogator, astrophysicist, photographer;

Dr. Olga Kovalic Seeney, twenty-nine, cook, biochemist, hydroponicist;

Dr. Ward Smith, forty-five, physician and surgeon, biologist;

Dr. Mary Jane Lyle Smith, twenty-six, atomics engineer, electronics and power technician;

Mr. Sergei Rimsky, thirty-five, electronics engineer, chemical engineer, practical machinist and instrumentation man, cryologist;

Mrs. Eleanora Alvarez Rimsky, thirty-two, geologist and selenologist, hydroponicist.

The crew had all needed skills, some having been acquired by intensive coaching during the weeks before blast-off. More important, they were mutually compatible.

The Envoy departed. During the first weeks her reports were picked up by private listeners. As signals became fainter, they were relayed by Earth's radio satellites. The crew seemed healthy and happy. Ringworm was the worst that Dr. Smith had to cope with the crew adapted to free fall, and anti-nausea drugs were not needed after the first week. If Captain Brant had disciplinary problems, he did not report them.

The Envoy achieved a parking orbit inside the orbit of Pho bos and spent two weeks in photographic survey. Then Captain Brant radioed: We will land at 1200 tomorrow GST just south of Lacus Soli.

No further message was received.

A QUARTER of an Earth century passed before Mars was again visited by humans. Six years after the Envoy went silent, the drone probe Zombie, sponsored by La Socit Astronautique Internationale, bridged the void and took up an orbit for the waiting period, then returned. Photographs by the robot vehicle showed a land unattractive by human standards; her instruments confirmed the thinness and unsuitability of Arean atmosphere to human life.

But the Zombie's pictures showed that the canals were engineering works and other details were interpreted as ruins of cities. A manned expedition would have been mounted had not World War III intervened.

But war and delay resulted in a stronger expedition than that of the lost Envoy. Federation Ship Champion, with an all-male crew of eighteen spacemen and carrying twenty-three male pioneers, made the crossing under Lyle Drive in nineteen days. The Champion landed south of Lacus Soli, as Captain van Tromp intended to search for the Envoy. The second expedition reported daily; three despatches were of special interest. The first was:

Rocket Ship Envoy located. No survivors.

The second was: Mars is inhabited.

The third: Correction to despatch 23-105: One survivor of Envoy located.

CAPTAIN WILLEM VAN TROMP was a man of humanity. He radioed ahead: My passenger must not be subjected to a public reception. Provide low-gee shuttle, stretcher and ambulance, and armed guard.

He sent his ship's surgeon to make sure that Valentine Michael Smith was installed in a suite in Bethesda Medical Center, transferred into a hydraulic bed, and protected from outside contact. Van Tromp went to an extraordinary session of the Federation High Council.

As Smith was being lifted into bed, the High Minister for Science was saying testily, Granted, Captain, that your authority as commander of what was nevertheless a scientific expedition gives you the right to order medical service to protect a person temporarily in your charge, I do not see why you now presume to interfere with my department. Why, Smith is a treasure trove of scientific information!

I suppose he is, sir.

Then why The science minister turned to the High Minister for Peace and Security. David? Will you issue instructions to your people? After all, one can't keep Professor Tiergarten and Doctor Okajima, to mention just two, cooling their heels.

The peace minister glanced at Captain van Tromp. The captain shook his head.

Why? demanded the science minister. You admit that he isn't sick.

Give the Captain a chance, Pierre, the peace minister advised. Well, Captain?

Smith isn't sick, sir, Captain van Tromp said, but he isn't well. He has never before been in a one-gravity field. He weighs two and a half times what he is used to and his muscles aren't up to it. He's not used to Earth-normal pressure. He's not used to anything and the strain is too much. Hell's bells, gentleman, I'm dog-tired myself and I was born on this planet.