2

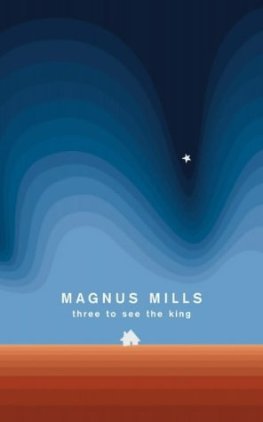

She was wrong there. I wasn't hiding from anybody. My house of tin was the place I'd chosen to live. It had nothing to do with hiding, yet the way she put it made me sound as though I'd run away.

You may ask: who was this woman? Well, I hardly knew her really. A friend of a friend I suppose you might say. The last person I'd have expected to turn up, if the truth be known, but she seemed keen on a guided tour so I invited her inside. It was the time of year when the stove had to be kept lit all the time, just to maintain some warmth. She gave a little shiver as I closed the door behind her, and then stood staring around with a sort of surprised smile or half-laugh on her face.

'It's practically bare,' she said.

'Yes,' I replied.

'But you can't live like this.'

'Why not?'

'You just can't.'

I think the sparseness of my existence had caught her out. I had no pictures on the walls to brighten them up, nor my oilier kind of decoration, and I suppose she was taken aback by how basic it all was. I pointed out that there was a pot of fresh coffee on top of the stove, meaning to show her that it wasn't all 'hardship', but I'm afraid she just laughed again and shook her head.

'Looks like we're going to have to get you sorted out,' she announced.

I realized from the amount of stuff she'd brought with her that she intended to stay around for a while. She had a whole trunkful of clothes, and a vanity case, not to mention the washstand and mirror. Fortunately there was lots of space, more than I needed really, so I told her she could use the upper floor.

I expect you thought my house of tin was a single-roomed affair with a bunk bed in one corner and a bucket in the other. Well, as a matter of fact, nothing could be further from the truth. The man who built it wanted more than just a shack to spend the winter in. He wanted two storeys and a stairway, and a sloping roof with gutters and drainpipes for the rainwater. He built it facing west-southwest, head-on to the wind, and sound enough for any storm. It's a proper house, I tell you, not the kind of ramshackle shanty you might find on some distant seashore where they fish in the morning and sleep in the afternoon. No, you wouldn't catch me living in a place like that. Much better to be somewhere that's going to hold together for a few years, which was why I chose a building foursquare and tall, with an upper floor.

I really thought this woman would be pleased to have a bit of room to herself, but when she saw the stairs she just took one look and said, 'They're very steep, aren't they?'

Well, of course they were steep! What else did she expect in a two storey house of tin? Alright, I admit it was quite a struggle getting the trunk and everything hoisted up, but the way she went on you'd have thought the stairs had been made steep deliberately.

This was what I couldn't understand about her. She'd come all this way to see me, even though we'd only met once or possibly twice before, and yet from the moment she arrived she was full of criticism. By the following morning I'd begun to think she didn't like my domestic arrangements at all. I had spent the whole night conscious of her moving around above me. She didn't seem able to settle down, and it turned out that the wind had kept her awake. I didn't ask her about her sleeplessness directly, of course, because it wouldn't have done for her to know I'd heard her every movement. When she came downstairs, however, the first thing she did was complain about the noise the wind made. Here was an obvious difference between the two of us. It has always astounded me that people can object to such things as being dazzled by sunlight, drenched by the rain or, as in this case, being kept awake by the wind. Surely one of the major appeals of living in a tin house is listening to that very sound! Before this woman turned up I had spent many an hour doing little else, day and night. As I said before, the wind never managed to find a gap to get inside. Nonetheless, it searched and whined incessantly beneath the corrugated eaves, producing a tune of infinite variations. There were times when it would bring with it rain, or else great dry sandstorms that rattled across the roof and added to the general din. These chance harmonics I found reassuring, comforting even, but I'm afraid my new guest heard them with different ears.

'What a racket!' she said, opening the door and looking outside. Then, to my surprise, she exclaimed, 'Oh, sweet!'

Apparently she thought it was quite endearing the way I'd hung out my washing on the line to dry. Personally, I couldn't see what was supposed to be so remarkable about it. After all, clothes will dry in no time in that wind, so it stood to reason to turn it to full use. Besides, I'd already been up and about for a couple of hours waiting for her to surface, so I thought I might as well get some clothes done. The result of my carrying out this simple chore was striking. She seemed instantly to forget about the wind keeping her awake all night, and now every object she laid eyes on was 'sweet'. She even liked the shovel that I kept on a hook on the back of the door! Maybe it was the morning sun that had put a different glint on things, but whatever the reason I must confess I enjoyed this change of tone. Without her noticing I closed the door again (to prevent the sand from getting inside), and we spent an agreeable morning getting her trunk properly unpacked. Now that the initial prickliness was over I was quite glad she'd come. All the same she took some getting used to. Later I came to understand that she was capable of enjoying my company and finding fault both at the same time, but in those first few days I wasn't sure what was going on.

Take the question of the mirror, for example. The one she'd brought with her was a full-length model, and it was still waiting to be moved to the upper floor. I put this job off for a while, then just when I was in the middle of lifting it up she announced it was probably better to leave it where it was.

'Don't worry,' I replied. 'It's not too heavy.'

'So you're taking it up are you?' she asked.

'Yes,' I said. 'Might as well.'

When finally I'd got it to the top of the stairs she came and joined me.

'You've got smears on it now,' she said. 'Look.'

'Couldn't be helped,' I answered.

'You didn't have to bring it up here at all. I'd have much preferred it down by the door. The light's more natural there.'