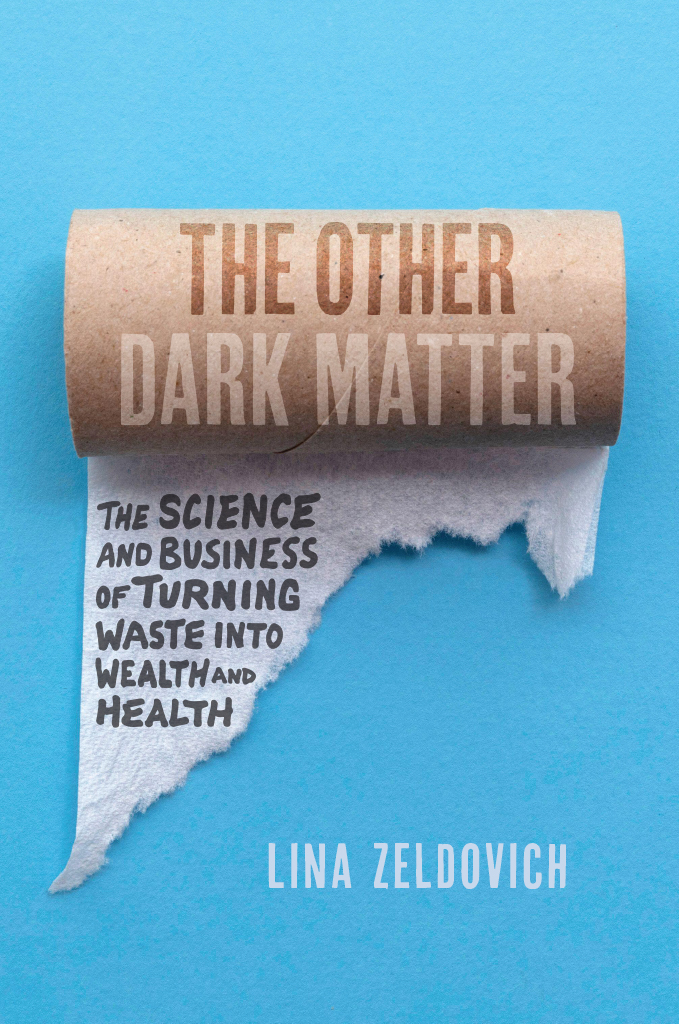

The Other Dark Matter

The Other Dark Matter

The Science and Business of Turning Waste into Wealth and Health

Lina Zeldovich

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by Lina Zeldovich

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-61557-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-81422-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226814223.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zeldovich, Lina, author.

Title: The other dark matter : the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health / Lina Zeldovich.

Other titles: Science and business of turning waste into wealth and health

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021013488 | ISBN 9780226615578 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226814223 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sewage disposal. | SewageRecycling. | Sewage sludgeRecycling. | Sewage disposalHistory. | Sewage sludge as fertilizer. | Sewage sludge fuel. | Biogas. | FecesTherapeutic use.

Classification: LCC TD741 .Z45 2021 | DDC 628.3/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021013488

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To my grandfather

who taught me to plant, grow, and harvest

To my parents

who forgot to teach me how to give up

To Dennis

who believed in me more than I believed in myself

To Tanya

who told me I could write a book

To Luba

who took on my unconventional idea

To my children

who put up with me while I wrote it

Contents

The History of Human Waste

How I Learned to Love the Excrement

Every fall, my grandfather would set off to do two things: prepare our small family farm for the long Russian winter and empty out our septic system.

He would don his sturdy overalls and heavy-duty gloves, both gray as the rainy sky above, tie two old beat-up buckets to long, thick ropes, and head out to the sewer tank buried by the fence surrounding our property. As he opened the pit, ringed with garden weeds and stinging nettles, the stink slowly wafted through the air, settling over our land like a small stomach-turning cloud. Yet my nose would get used to it, and soon I wouldnt be bothered by it at all. I even wanted to help, but my grandmother wouldnt let me go near the pitshe was afraid Id fall in.

Todays septic tanks can last for years without being emptied, but ours would fill up much more quickly. We could have called a service to empty it, but my grandfather wouldnt let all those riches go to waste. He had a system.

Dressed in his hazard suit, he would spend a day or two dipping buckets into the foul brown liquid and distributing it over our land. Sometimes he carried the buckets by hand, sometimes he balanced them on a koromysloan arched wooden pole placed over the shoulders to distribute weight evenly. He walked slowly to avoid splashing the stuff onto his clothes and boots.

He didnt just dump the sludge wherever. He poked small holes in the strawberry and tomato patches, where the plants were already shriveled, expecting winterand poured the goo into them, deep into the earth. He dug little trenches around the apple trees and emptied his buckets onto their roots. And he also dumped a bunch into one of the compost pits, adding it to the already accumulated dead plants, leaves, and our kitchen food scraps. The compost pits operated on a rotating schedule. At the end of the season, hed close up the current one for a couple of years, leaving it to ferment and biodegrade. When he opened it again two seasons later, after the snow melted and planting time arrived, all the original biomass was gone. The pit was full of soft, black dirt teeming with fat, lazy earthworms that crawled around slowly, too heavy from gobbling down all that food. The sewage odor was gone, too. Instead, the pit smelled of rich, fertile soil, nature, spring, and the promise of the next harvest. And it made me hungry because I thought of all the food we were going to grow with it.

And so when the next fall rolled around, the stinky sewage pit didnt disgust me. It was simply a part of life, of the natural cycle necessary to grow food and put dinner on the table. I loved growing everythingstrawberries, apples, tomatoes. As I puttered along with Grandpa, he taught me what plants needed to thrive. I liked to sow and I liked to harvest. I even liked to weed. After weeding, the patches looked so clean and orderly that you could just see the fruit starting to burgeon faster. Our farm wasnt big, but it yielded enough veggies and berries to pickle and preserve for the long Russian winters, when nutrients were scarce. And we grew so many apples that they lasted in our cellar through spring.

One of my grandmothers was a doctor, the other a chemist, and my mother and father were working on their dissertations in mechanics and physics, respectively. Before I started school, I knew about the perilous microbes that lurk in the soil, our dogs poop, and our own excrement. Thats why I had to wash my hands twice after planting, get the muck out from under my nails, and carefully scrape the garden dirt off my boots before entering the house. Washing everything was essential. We had no hot water in the house, so Grandma would heat up some for me. She had a process for cleaning Grandpa after his sewage excavations, too. He took off his hazardous overalls outside, and Grandma stuck them in a metal vat full of water, which she would later boil on the stove for a half hour until all the pathogens were dead. She didnt cook his boots because that would destroy them, so she just scalded them with boiling water. The germs were taken very seriously and given no chance to spread. When we got sick, it was mostly from the bitter winter cold. Diarrhea was rare. We just didnt get that many stomach bugs. We were quite aware of the dangers of raw sewage.

My grandfather, too, was well educated for his time. He had two college degrees, one in agriculture and one in engineering, so he combined knowledge from both with the wisdom of the generations of farmers in his family. Today, we may call it organic farming, composting, recycling, or the circular economy. But for him it was, simply, the way of life. He did use some inorganic fertilizer from heavy-duty plastic bags that he kept in the shed, but he did so sparingly. Inorganic fertilizers gave plants too strong a boost, and that wasnt a good thing, he thought. Manure, whether cow or human, was a natural way to feed your fields. You fed your land like you fed people.

The Russian equivalent of the word fertilizer is udobrenie, which comes from the word dobr, meaning good and rich. Udobrenie meant returning all that good stuff to the earth. Even the common Russian colloquialisms that revolve around the toilet recognize that. When toddlers were being potty trained, we jokingly referred to the moment they had to go as giving out

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).