For Romilly,

and for Mum & Dad.

Thank you.

In memory of the species that have vanished.

I would say that there exist a thousand unbreakable links between each of us and everything else, and that our dignity and our chances are one. The farthest star and the mud at our feet are a family; and there is no decency or sense in honouring one thing, or a few things, and then closing the list. The pine tree, the leopard, the Platte River, and ourselves we are at risk together, or we are on our way to a sustainable world together. We are each others destiny.

Mary Oliver

Winter Hours, 1999

CONTENTS

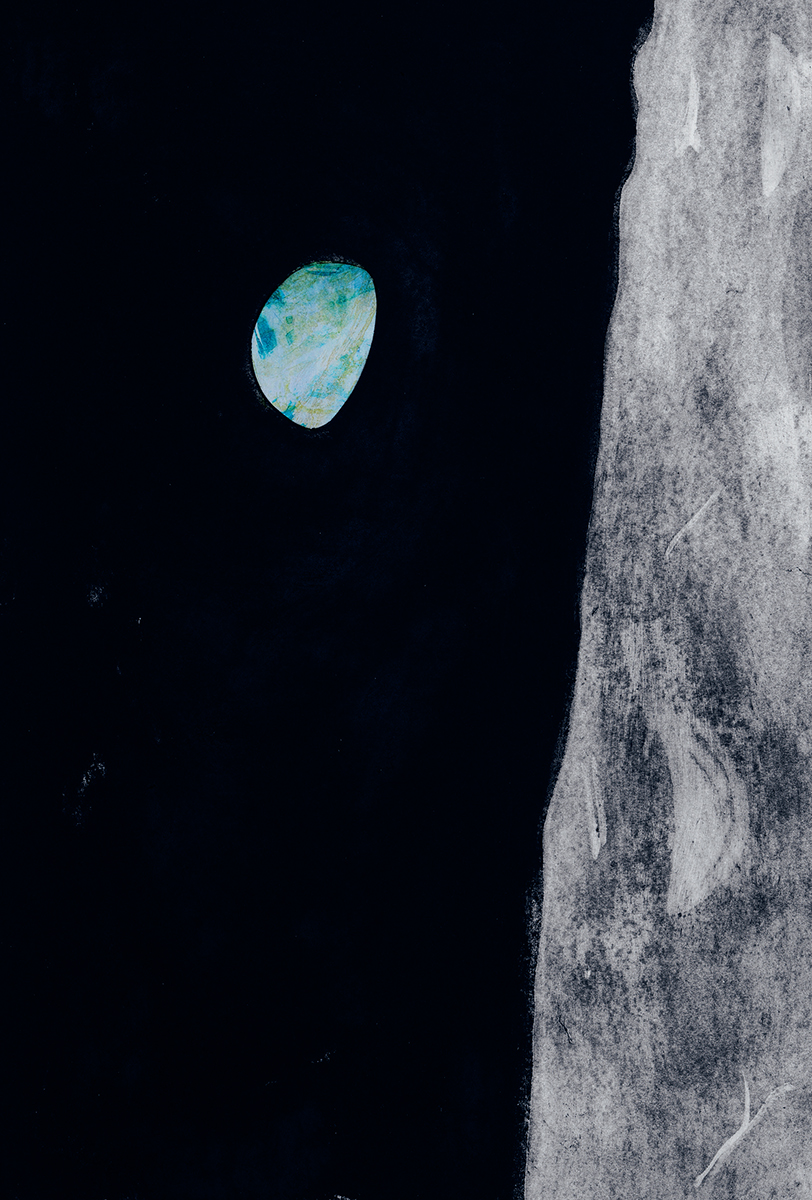

The craft is noisy with the buzz of electrical equipment, the mechanical clink of metal on metal, the hiss of static on the radio. Sometimes there is laughter, often the calm, toneless exchange of technical information, the confirmation of levels checked, switches on or off. Out of the last seventy-five hours, they have had so little sleep. Thin metal sheets separate them from the darkness hundreds of degrees below freezing.

Hurtling through space at almost a mile a second, this was the fourth of the ten lunar orbits they would complete within twenty hours. Now leaving the far side of the moon, Borman began to roll the craft and there it was, a thin arc of shining blue, the Earth, edging over the distant horizon of the wax-grey moon. At first the crew did not see it.

The following exchanges took place on 24th December 1968 and began at 075 hours, 46 minutes, 47 seconds into the Apollo 8 mission:

Anders (photographing the lunar surface for possible landing spots): There is one dark hole, and I couldnt get a quick enough look at it to see if it might be anything volcanic

Anders: Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Heres the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!

Borman: Hey, dont take that, its not scheduled. [Laughter.]

Anders: [Laughter.] You got a colour film, Jim?

Anders: Hand me that roll of colour, quick, will you

Lovell: Oh man, thats great!

Anders: Hurry. Quick.

Borman: Gee.

Lovell: Its down here?

Anders: Just grab me a colour. That colour exterior.

Anders: Hurry up!

Borman: Got one?

Anders: Yeah, Im looking for one.

Lovell: C 368?

Anders: Anything, quick.

Lovell: Here.

Anders: Well, I think we missed it.

Lovell: Hey, I got it right here!

Anders: Let let me get it out this window. Its a lot clearer.

Lovell: Bill, I got it framed; its very clear right here.

The first of two colour images of the Earthrise was taken at 075:48:39.

Lovell: You got it?

Anders: Yep.

Borman: Well, take several of them.

Lovell: Take several of them! Here, give it to me.

Anders: Wait a minute, lets get the right setting, here now; just calm down. Calm down, Lovell.

Lovell: Well, I got it ri Oh, thats a beautiful shot 250 at f/ 11.

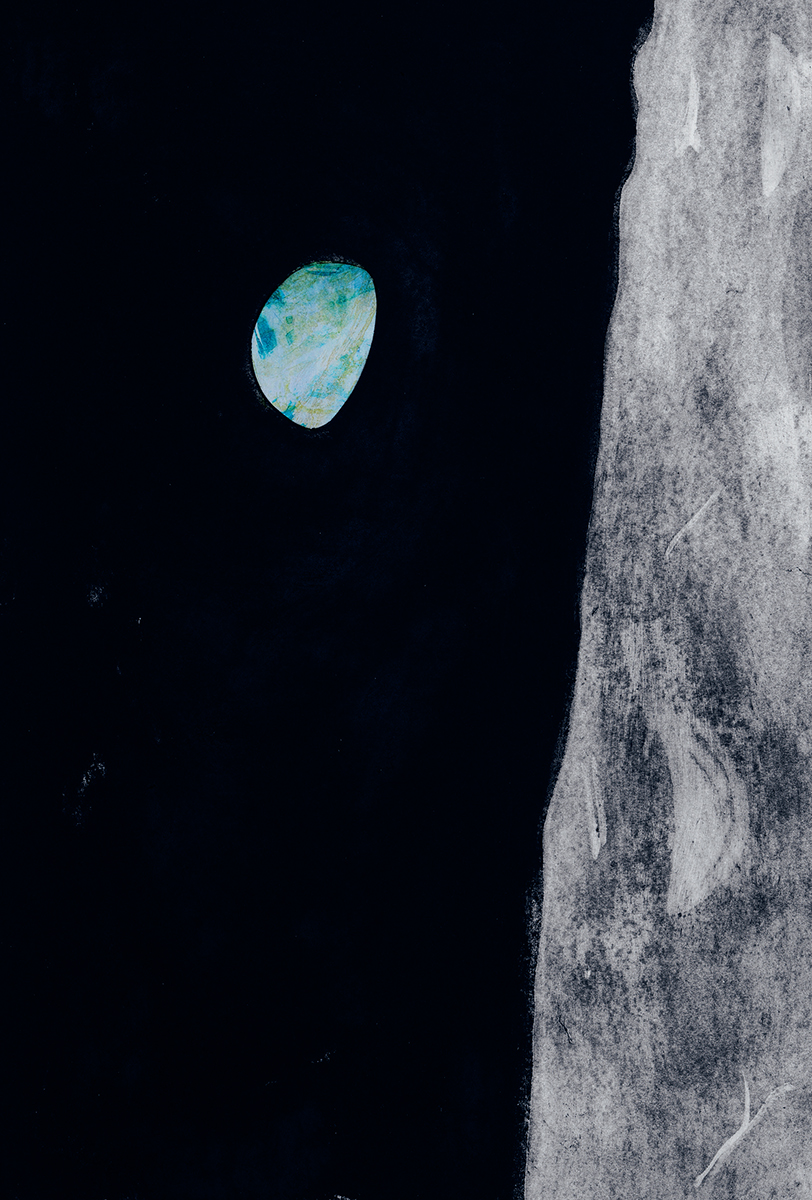

And that was the image they brought back. The Earth, bright with colour, glows beside the monochrome edge of the moon and hangs in the emptiness of space. In the photograph you can see the gleaming oceans and the swirling whorls of cloud. Through the gaps in these, you can just discern the browns and greens of Africa. Even from 376,000 km away, the planet looks as if it is dynamic, alive.

They had gone for the moon but returned with the Earth. The earliest photographs of our planet were blurry fragments of the whole; this was the first time anyone had taken a colour photograph of the Earth with the moon. It showed how beautiful the world was: how vulnerable, how alone, and how unlike anything else. It emerges from an infinite darkness, blacker than night.

By 1968 the journey of water molecules shown in the ice, oceans and clouds of the photograph was already understood. More recently discovered is how much oxygen is produced by those blue oceans and how much carbon dioxide they absorb. These cycles connect all living things. Fuelled by the light and heat of the sun, a continuous stream of energy, the planets biosphere is a self-renewing system of life which, for the last 300,000 years, and until very recently, has shown remarkable stability.

The day the Apollo 8 photograph was taken was Christmas Eve, and the crew read the verses of Genesis describing the beginning of the world, ending with, And God called the dry land Earth. And the gathering together of the waters called he seas. And God saw that it was good. And from the crew of the Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.

In the eighteen months it has taken me to research this book, 107 species have been declared extinct.

Though extinction plays a role in evolution, it is thought the current rate of extinction is happening a thousand times faster than before humans existed. Death is a necessary part of every species cycle of life; extinction ends this cycle. We are destroying without knowing the value of what we destroy or worse, knowing full well.

When I was a child, the fields around our house were full of life, thick with meadow clary, Jack-go-to-bed-at-noon, clover, buttercups, cuckooflowers, cowslips and dandelions, and busy with the hum of insects. The seasons were still defined. In the field of rye grass outside my window now, there are no flowers. At its edges, dock leaves are contorted from the effects of herbicides. There are few sounds except the motorway a couple of miles from here. Swallows no longer visit, nor do we hear the call of the cuckoo. Crows flap across the fields. At night, the stars are obscured.

We are depriving ourselves of the raw material of poetry. The vulnerability of the species we endanger, their inability to speak for themselves, is what first made me want to make engravings of them. As I did so, I was drawn into their lives, their mystery, their otherness and their similarity to us.

SOME OF THE SPECIES THAT WERE DECLARED EXTINCT DURING THE WRITING OF THIS BOOK

I wanted to tell their stories. As far as it is possible for someone without a scientific background to do so, I have tried to do them justice and to convey something of our impact on the planet, and on the creatures with which we share it. I was lucky enough to be given an artist residency with the Cambridge Conservation Initiative (CCI), a collaboration between Cambridge University and nine leading biodiversity conservation organisations, including the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Here I encountered people with extraordinary knowledge and dedication who have devoted their careers to the conservation of particular habitats or species.