Contents

Guide

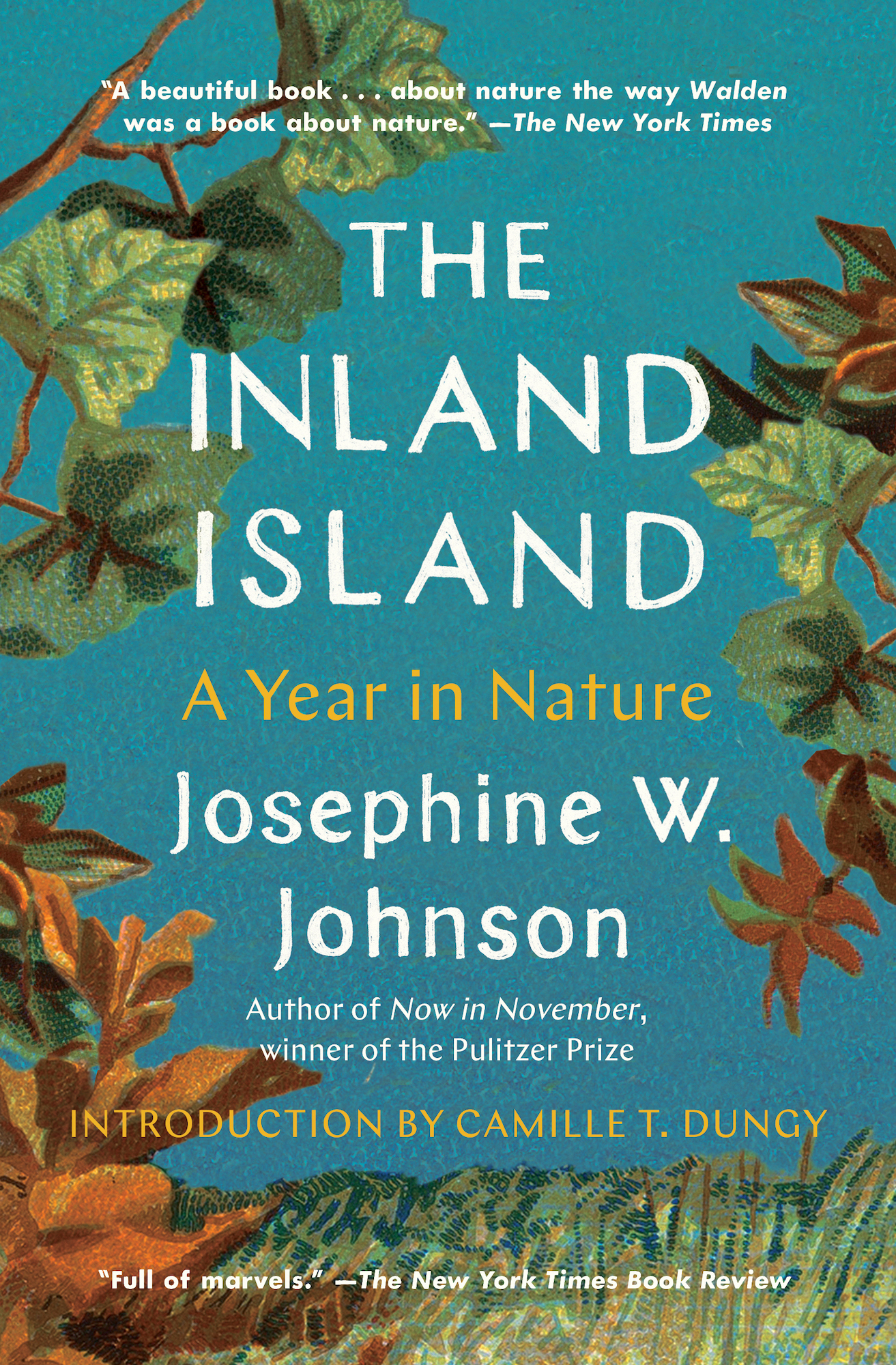

A beautiful book about nature the way Walden was a book about nature. The New York Times

The Inland Island

A Year in Nature

Josephine W. Johnson

Author of Now in November, winner of the Pulitzer Prize

Introduction by Camille T. Dungy

Full of marvels. The New York Times Book Review

THE PATH HER PEN DESCRIBES

I would have liked to take a walk alongside Josephine Johnson. To tromp, as she often did, across the thirty-seven Ohio acres she called home during the final decades of a life that spanned the twentieth century. To walk the land she let transform from mown pasture back to woods, and which she describes in The Inland Island with precise and clear-eyed care. Im a walker, too, and I can feel in Johnsons lines the breath and tread of a person who measures time by the pace of her stride and the color of leaves on the limbs of trees. I would have liked to walk with Johnson, observing a huddle of ladybugs or the twisted trunk of an Osage orange, but she died in February 1990, at the age of seventy-nine, and I never had the chance. Reading The Inland Island, though, I feel as if shes right beside me, walking, walking, witnessing the world.

If Id had a chance to take that walk with Johnson, I have a feeling she would not have talked much. Shed have been too busy watching and recording everything she saw. But I imagine she might have turned to me with the occasional question. Do you want to go over and see whats growing near the clear stream, or the polluted one? perhaps, or What will you do today to protest the war? or Did you hear that robin singing from the wild cherry tree? If The Inland Island is any indication, she wouldnt wait for an answer. Johnson writes in the present tense, as if she understands that what is required of us, always, is to be present, fully, in the place and time we are. As if she understood what had always been important and would remain ever so. She writes of the ugly and gorgeous in equal turns. This is a work of radical witness. Reading The Inland Island feels like being with Walter Benjamins Angel of History, if the Angel of History were a midwestern amateur naturalist. Johnson does not judge, nor does she demand particular action from anyone or anything. She walks and she watches and she patiently describes.

The Inland Island was published in 1969, thirty-five years after Johnsons Pulitzer Prizewinning debut novel, Now in November. In 1935, at just twenty-five years old, Johnson became the youngest person ever to win the prize for fiction, and she remains the youngest person with that honor to this day. But The Inland Island is the work of a woman in her late middle age. This memoir, recording twelve months of her life on the land, is filled with the loving attention of someone who has learned how to live on through grave disappointment. The Vietnam War was much on her mind as she walked through the woods shed let go back to the wild. Her son was facing jail time for activities related to antiwar protest, and she wonders about withholding her own tax dollars so as not to be party to violence she didnt condone. She thinks about Black peoples struggles for equal rights. She wonders about what readers might think of her book, having faced dispiriting reception for some of the political stances shed included in books she wrote after Now in November. She worries about the fox who roams nearby, a fox she knows local hunters want to kill. She considers what it must be like to be a caterpillar and, also, what it must be like to be a mink. She thinks about what it means to be American and white. There are all manner of snow, both cruel and kind. There is the snow that falls like needles and drifts in hard ridges on the dead cornfields, is bitterly cold, coming down from the northwest and driving into the earth like knives, she observes, and I find myself nodding in chilled recognition. She writes about flowers and boorish neighbors with equal grace and precision and something that, even when what she witnesses hurts, I can best identify as love.

I would have liked to walk with Josephine Johnson across her thirty-seven acres. Thanks to this rerelease of The Inland Island, it seems as if I can.

Camille T. Dungy

Fort Collins, Colorado

December 2021

T he new year lies before us. One stands on a high firm place. Alls clean and clear. The air is fresh, not freezing. Hoarfrost is on the valley trees, grey ice on the pond and glitter on the grass clumps. The delicate dead grasses are frosted, the plowed earth cold and bitter-chocolate brown.

This beautiful slice of land is all thats left. Its my lifeblood. The old house is abandoned down in the valley where the mammoth bones were found in the quarry. We are on this side the ridge from that valley now. The children are gone. The horses gone. The old house gone. Whats left? A world of trees, wild birds, wild weedsa world of singular briary beauty that will last my life. The landmy alderliefestthe most beloved, that which has held the longest possession of the heart.

I was born of Franklins on my mothers side, and the Franklin was a landowner, a freeman, in the Anglo-Saxon days. I have had a love for the land all my life, and today when all life is a life against nature, against mans whole being, there is a sense of urgency, a need to record and cherish, and to share this love before it is too late. Time passesmine and the lands.

This place, just short of the timber forty, has steep hills, two creeks, thousands of trees, and a network of small ravines or draws. There is one-half acre of flatland, and the house sits on it. The windows, wide as the walls, look out and down into a narrow valley made by a widening creek with steep clay banks. This creek bed grows in every storm, sometimes east, sometimes west. When it moves east it eats under the hill on which the house stands. In the storm nights one can hear the great rocks grinding in the rush of the waterrocks born in the beginning of the world, once the bottom of vast oceansnow upended, rolled and shoaled downstream, by a small midwestern storm.

The place begins at the top of the hill, a narrow entrance between old lilac bushes. There isnt any gate, only a space between the old barn and the lilac bush for cars to squeeze through, and every day one hears the crush and rattle of lilac twigs against glass. Which may annoy, and then may notfor no man or woman or child, coming down that drive for the first time, has failed to say, My, but its quiet back up here, I wish I had a place like this. I wish that they had, too. I wish there were great trees left and great trees planted. Who plants an acorn now for his sons oak? Theres no room for oak trees in this world. And soon therell be no room for sons.

The elm by the gateway is not like the beautiful wine-glass elms of New England, but it healed itself of a weeping ulcer, and it throws up a sturdy fountain of branches against the sky. Under it is the well, a well of deep cold water, whose pump was cured by the plumber of coughing up red clay. And the pump, the little rascal, as he gravely spoke of it in its gasping, seems his property, so closely has he come to be its master, its translator, friend and father. He knows its valves and snifters intimately, and only once did it catch him by surprise. The blacksnake in the rotor box. You learn something new all the time, he said. Everything has a first.