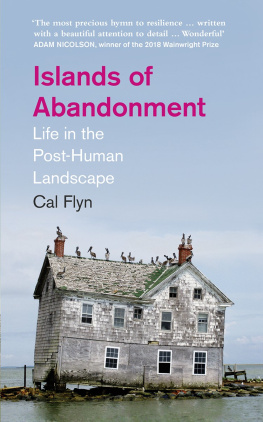

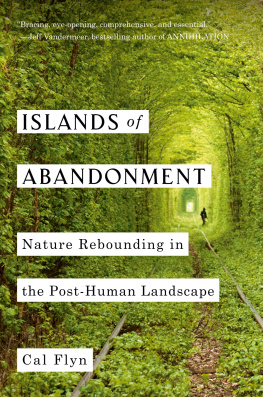

ISLANDS OF ABANDONMENT

Life in the Post-Human Landscape

Cal Flyn

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road,

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

Copyright Cal Flyn 2021

Cal Flyn asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

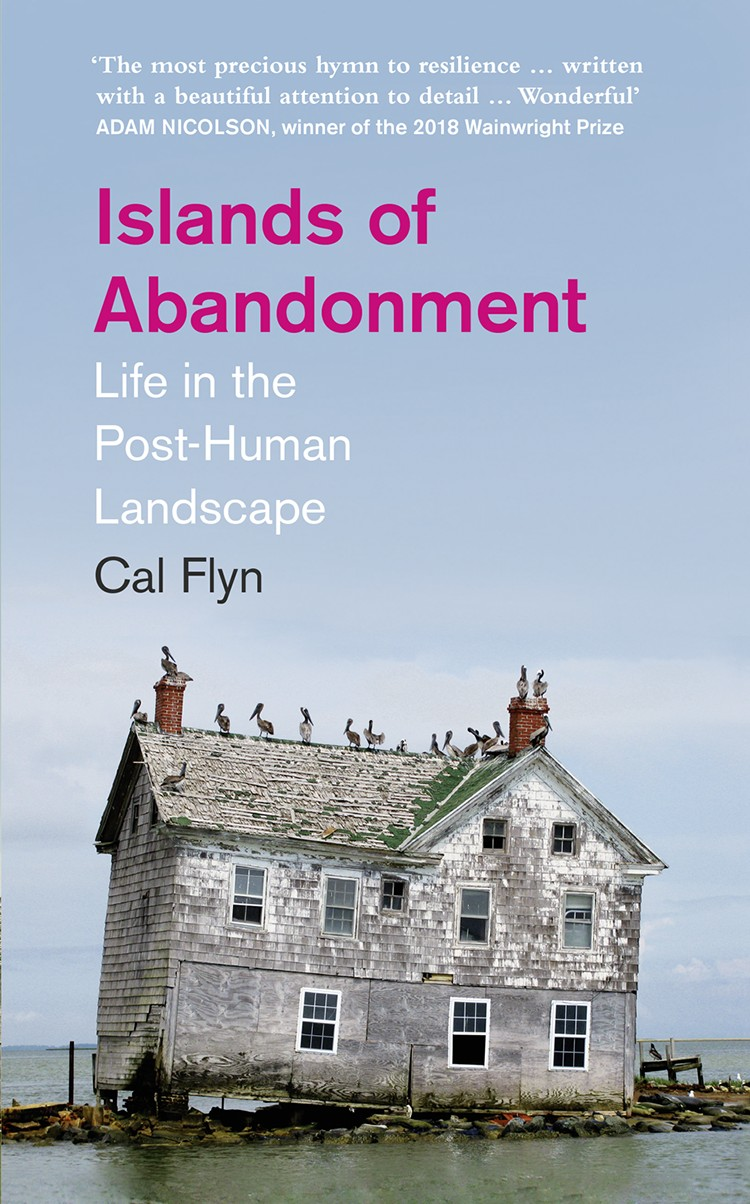

Cover photograph: Last House on Holland Island, May 2010 baldeaglebluff

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008329761

Ebook Edition January 2021 ISBN: 9780008329785

Version: 2021-01-07

For Rich,

who makes me so very happy

Contents

I t is cool in the tunnels, not cold as it was outside. And dark, very dark. The air is almost still, but not quite theres a trace of movement that scuffs the leaves that lie in low drifts along the edges where wall meets floor. Perhaps its this that gives me the unnerving impression of not being entirely alone.

To reach the inner sanctum, I must step over bodies of gulls and rabbits that have been trapped here in the outer passage or else crawled in here to die. I do so carefully, averting my eyes as much I can. After a while, spooked by the flash of the torch against stone, I switch it off, and let my eyes adjust. Theres just enough light from where the heavy metal door hangs ajar to let me navigate the wide stone stairs and move deeper into the bowels of the old fort.

Once plastered white, the walls are marbled with grime, misted here and there in deep mould-green. Soon, though, its too dark to tell. Despite stern words, spoken inwards, I feel my pulse quicken. At every corner, where the unknown looms tenebrous and forbidding, I need to force myself forward take a breath, touch my fingers to the wall, feel my way around. I smell wet stone, soil, decay; the smell of the crypt. When its hopeless to do anything else, I switch my torch back on.

Its true, then. Im not alone. Or, not quite. Along the rough-hewn walls, my halo of light picks out first one dark body, and then another. I find three, clustered together, close to the ground, wings pressed tight like hands together in prayer. I have to get down in the dust on my hands and knees to look at them, to see the detail of them: the intricate adornment of the outer wings a fretwork of ebony and sable through which faint threads of copper glint. Butterflies, still dormant. Soon to wake.

This is Inchkeith, an island in the Firth of Forth, just four miles across the water from Edinburgh. In its time, (banished there till God provided for their health), then a plague hospital and even an island prison, with water for walls.

So isolated was it, and yet so continually in view from the Scottish capital as a rocky mirage upon the horizon that it is said to have taken hold of the imagination of King James IV of Scotland, who saw in Inchkeith the potential for a notorious language-deprivation experiment. He, a polymath with a roving mind, was much taken up with concerns of Renaissance science, and practised both bloodletting and the extraction of teeth. James sank huge sums into research into alchemy, human flight, and according to a sixteenth-century chronicler transporting to Inchkeith two newborn infants in the care of a deaf nursemaid, in the hope that the children, sequestered from the corrupting influence of society, would grow up to speak the prelapsarian language of God.

Known as the forbidden experiment for the cruelty of inflicting such extreme isolation and irreversible social harm upon a child, its results were inconclusive. Some sayes they . I suppose it depends what sort of God they were looking for.

In time, Inchkeith became a fortress isle, held sporadically by the English during times of war and, latterly after great shedding of blood the French. By the Second World War, this island half a mile in length was home to more than a thousand soldiers, with gun emplacements standing in tense watch over the entrance to the Forth. After Armistice, too small and damaged and difficult to access to bother with in peacetime, Inchkeith was abandoned once more.

But as the island has fallen into obscurity, it has risen in environmental significance. Before the 1940s, only one seabird was known to nest there: the eider. In the decades since, it has become the breeding ground of a dozen more, and countless other visitors. By early summer, the cliffs will be heaving with life and limewashed with droppings, every ledge occupied with muddled nests of rotting seaweed or freckled eggs sitting directly on the stone, every species taking up its station in the strata of life: shags bedding down on the spray-spattered rocks, the sleek, monochrome guillemots on the lower reaches of the cliffs; the gnomish razorbills, with their aquiline bills, on the next floor up; the elegant greyscale kittiwakes taking up residence in the penthouse and all of them shrieking in constant querulous protest at their neighbours.

Above, on what was once the lighthouse keepers pasture, buxom puffins, with their candy-striped beaks, take up residence in warrens. Winter wrens and barn swallows and rock pigeons have taken ownership of the old military buildings which sag and split open like rotting fruit. Elder grows in thickets inside the roofless buildings, huddling together as if for warmth against the bitter wind that comes battering in off the North Sea.

As the weather draws in, grey seals heave themselves up concrete slipways grown slick with seaweed, to bask in weak sunlight a thousand at a time, finding sanctuary enough here in the middle of a shipping channel to pup. Their spaniel-eyed babies spend the winter lolling in the tussocky grass, scooching up paths, and investigating the ruins. Around the same time, the butterflies and moths that blow over the island like smoke will begin to crawl into the dark tunnels that riddle the slopes to hibernate blue-sequined peacock butterflies; the shining, shield-like herald moth, or scallop-edged small tortoiseshells like these. One twitches a leg. I leave them be.

I feel a draught, a faint movement that draws me upstairs. Far above, I see a glimmer of daylight. The faint alkaline taste of guano in the air. I find a door, half-rusted shut, but not past opening, and then I am out, standing alone at the very prow of the island, like the figurehead of a ship, looking out to sea from what was once the circular crater of the gun turret, the last ditch defences of a war long over.

The wind is moving fast through empty space: mighty currents of the air, sucking the breath from my lungs. And the birds the birds rise up as one great moving, wheeling mass. Screaming, squalling, furious to find me here, now, on this island of abandonment.