Also by Cal Flyn

Thicker Than Water

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in hardcover in Great Britain by William Collins, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, London, in 2021.

First American edition published by Viking.

Copyright 2021 by Cal Flyn

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following images:

The Five Sisters bing. Copyright 1975 by Dave Henniker.

Copyright Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

produced by Dr. Glenn Matlock, Associate Professor, Environmental and Plant Biology Department, Ohio University, based on data from: Greeley, William B, 1925, The Relation of Geography to Timber Supply, Economic Geography 1: 111; Williams, Michael, 1989, Americans and Their Forests, Cambridge University Press, pp. 436437; Proportion of Land that is Forested, US Forest Service Forest Inventory Analysis, 2007.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Flyn, Cal, author.

Title: Islands of abandonment : nature rebounding in the post-human landscape / Cal Flyn.

Description: New York : Viking, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020041722 (print) | LCCN 2020041723 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984878199 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781984878205 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Restoration ecology. | Resilience (Ecology) | Environmental disasters. | Ecosystem health. | Landscape changes. | NatureEffect of human beings on.

Classification: LCC QH541.15.R45 F59 2021 (print) | LCC QH541.15.R45 (ebook) | DDC 333.73/153dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020041722

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020041723

Designed by Alexis Farabaugh, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

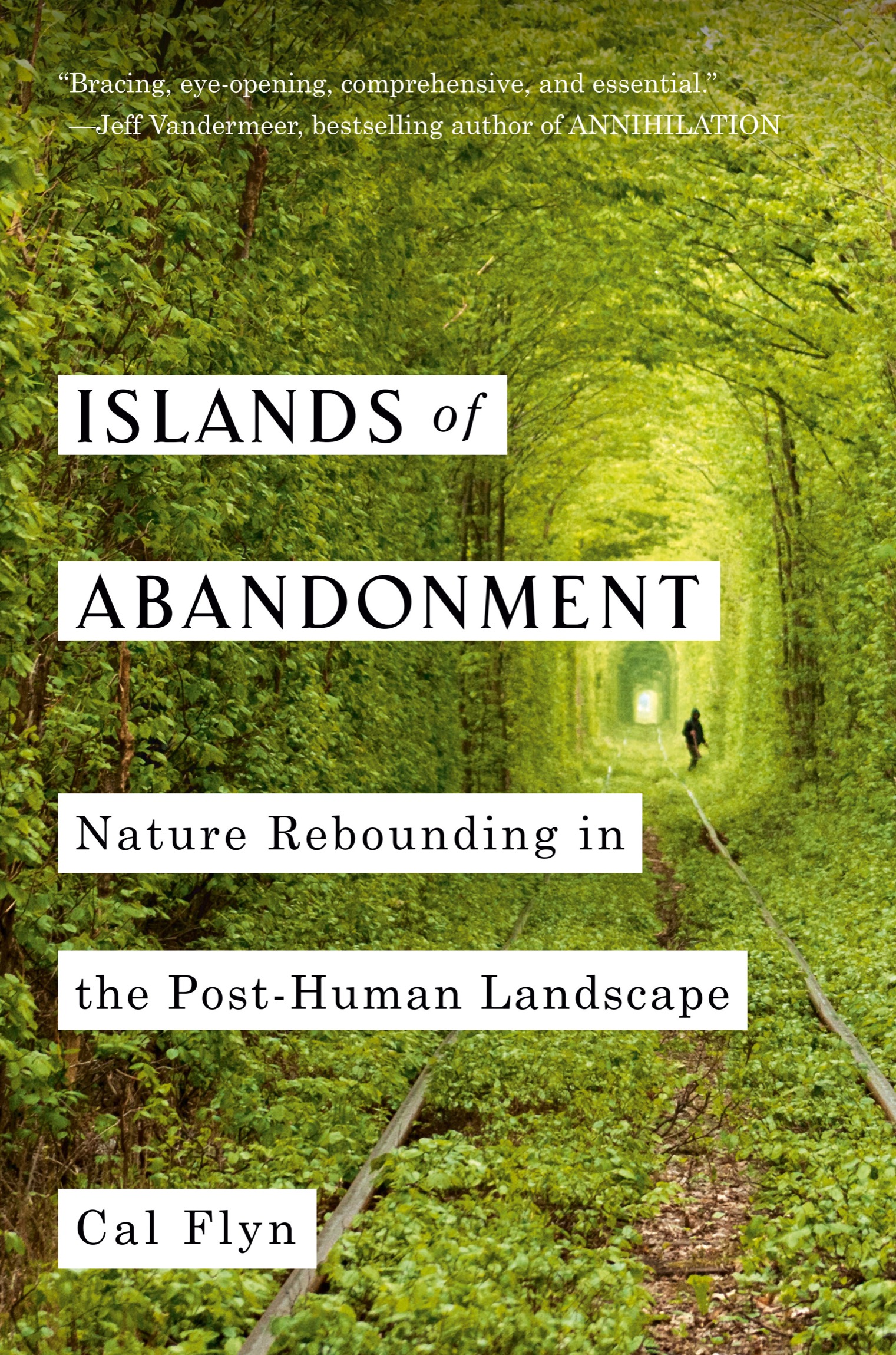

Cover design: Paul Buckley

Cover photograph: Olga Pustovoit

pid_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

For Rich,

Who makes me so very happy

Contents

INVOCATION

Forth Islands, Scotland

It is cool in the tunnels, not cold as it was outside. And dark, very dark. The air is almost still, but not quitetheres a trace of movement that scuffs the leaves that lie in low drifts along the edges where wall meets floor. Perhaps its this that gives me the unnerving impression of not being entirely alone.

To reach the inner sanctum, I must step over bodies of gulls and rabbits that have been trapped here in the outer passage or else crawled in here to die. I do so carefully, averting my eyes as much as I can. After a while, spooked by the glare of the flashlight against stone, I switch it off, and let my eyes adjust. Theres just enough light from where the heavy metal door hangs ajar to let me navigate the wide stone stairs and move deeper into the bowels of the old fort.

Once plastered white, the walls are marbled with grime, misted here and there in deep mold-green. Soon, though, its too dark to tell. Despite stern words, spoken inward, I feel my pulse quicken. At every corner, where the unknown looms tenebrous and forbidding, I need to force myself forwardtake a breath, touch my fingers to the wall, feel my way around. I smell wet stone, soil, decay; the smell of the crypt. When its hopeless to do anything else, I switch my flashlight back on.

Its true, then. Im not alone. Or, not quite. Along the rough-hewn walls, my halo of light picks out first one dark body, and then another. I find three, clustered together, close to the ground, wings pressed tight like hands together in prayer. I have to get down in the dust on my hands and knees to look at them, to see the detail of them: the intricate adornment of the outer wingsa fretwork of ebony and sable through which faint threads of copper glint. Butterflies, still dormant. Soon to wake.

This is Inchkeith, an island in the Firth of Forth, just four miles across the water from Edinburgh. In its time, Inchkeith has been many things: the remote site for an early Christian school of the prophets, later a quarantine island for those stricken with syphilis (banished there till God provided for their health), then a plague hospital and even an island prison, with water for walls.

So isolated was it, and yet so continually in view from the Scottish capitalas a rocky mirage upon the horizonthat it is said to have taken hold of the imagination of King James IV of Scotland, who saw in Inchkeith the potential for a notorious language-deprivation experiment. He, a polymath with a roving mind, was much taken up with concerns of Renaissance science, and practiced both bloodletting and the extraction of teeth. James sank huge sums into research into alchemy, human flight, andaccording to a sixteenth-century chroniclertransporting to Inchkeith two newborn infants in the care of a deaf nursemaid, in the hope that the children, sequestered from the corrupting influence of society, would grow up to speak the prelapsarian language of God.

Known as the forbidden experiment for the cruelty of inflicting such extreme isolation and irreversible social harm upon a child, its results were inconclusive. (Some sayes they spak guid Hebrew, reported the chronicler, slyly, but I knaw not. Others evoked a brutish babble.) I suppose it depends what sort of God they were looking for.

In time, Inchkeith became a fortress isle, held sporadically by the English during times of war and, laterafter great shedding of bloodthe French. By the Second World War, this island half a mile in length was home to more than a thousand soldiers, with gun emplacements standing in tense watch over the entrance to the Forth. After Armistice, being too small and damaged and difficult to access to bother with in peacetime, the island was abandoned once more.

But as Inchkeith has fallen into obscurity, it has risen in environmental significance. Before the 1940s, only one seabird was known to nest there: the eider. In the decades since, it has become breeding ground to a dozen more, and hosted countless other visitors. By early summer, the cliffs will be heaving with life and limewashed with droppings, every ledge occupied with muddled nests of rotting seaweed or freckled eggs sitting directly on the stone, every species taking up its station in the strata of life: shags bedding down on the spray-spattered rocks; the sleek, monochrome guillemots on the lower reaches of the cliffs; the gnomish razorbills, with their aquiline profiles on the next floor up; the elegant grayscale kittiwakes in the penthouseand all of them shrieking in constant querulous protest at their neighbors.

Above, on what was once the lighthouse keepers pasture, buxom puffins, with their candy-striped beaks, take up residence in warrens. Winter wrens and barn swallows and rock pigeons have taken ownership of the old military buildings which sag and split open like rotting fruit. Elder grows in thickets inside the roofless buildings, huddling together as if for warmth against the bitter wind that comes battering in off the North Sea.