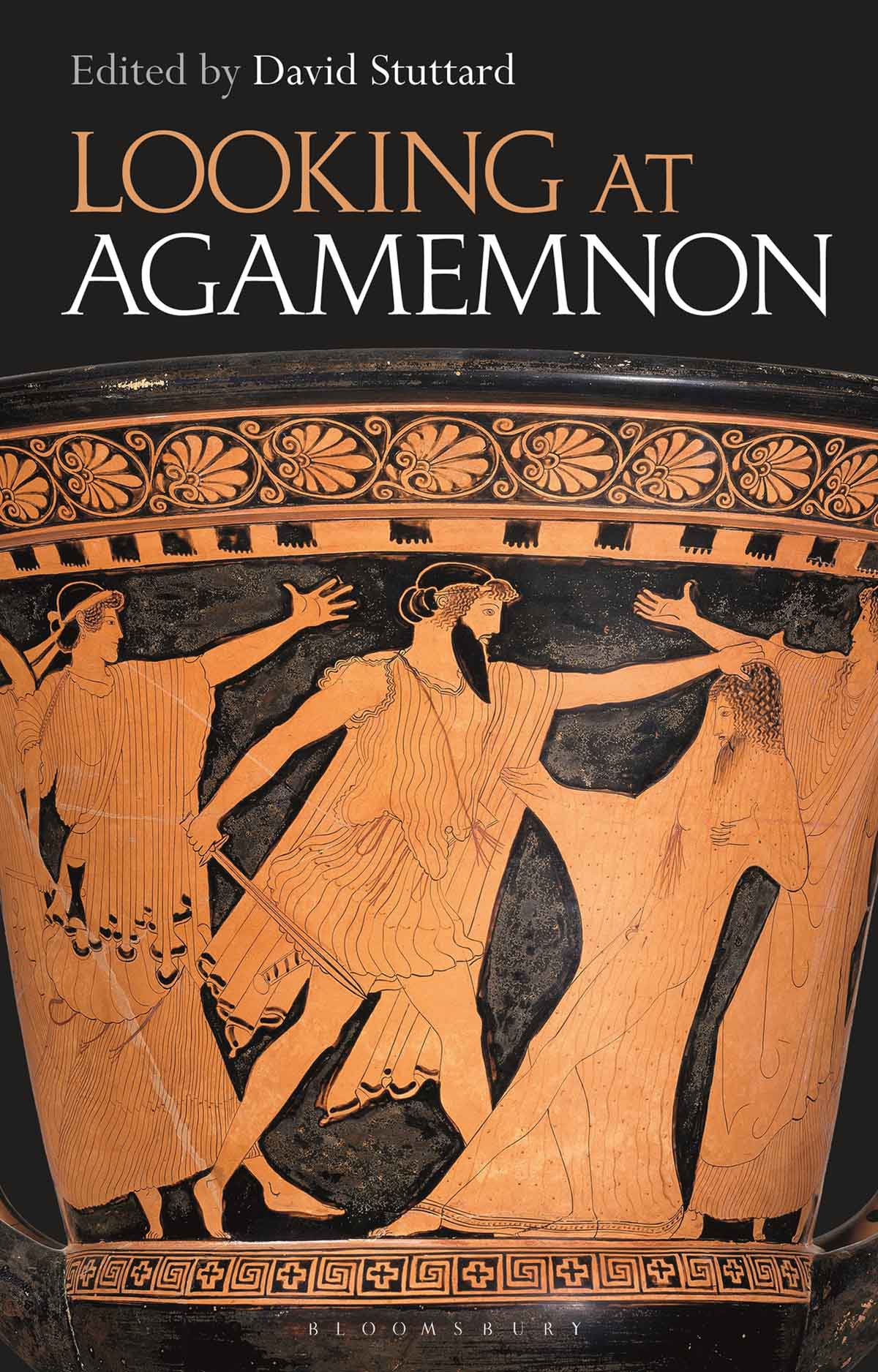

Looking at Agamemnon

Also available from Bloomsbury

Looking at Ajax, edited by David Stuttard

Looking at Antigone, edited by David Stuttard

Looking at Bacchae, edited by David Stuttard

Looking at Lysistrata, edited by David Stuttard

Looking at Medea, edited by David Stuttard

Contents

Michael Carroll is Lecturer in Greek Literature at the University of St Andrews.

Robert Garland is Roy D. and Margaret B. Wooster Professor of the Classics Emeritus, Colgate University.

Alex F. Garvie is Emeritus Professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow.

Edith Hall is Professor in the Department of Classics and Centre for Hellenic Studies at Kings College.

Sophie Mills is Professor in the Department of Classics, University of North Carolina Asheville.

Rush Rehm is Professor of Theatre and Performance Studies, and of Classics at Stanford University.

Hanna Roisman is Professor of Classics, Arnold Bernhard Professor of Arts and Humanities, Emerita, Colby College.

Richard Seaford is Emeritus Professor of Ancient Greek at the University of Exeter.

Alan H. Sommerstein is Emeritus Professor of Greek at the University of Nottingham.

David Stuttard is a freelance writer, historian and theatre director, and Fellow of Goodenough College, London.

Isabelle Torrance is Professor of Classical Reception at Aarhus University.

Anna Uhlig is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of California, Davis.

Betine van Zyl Smit is former Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Nottingham.

Aeschylus Agamemnon is the first play in the only extant Greek tragic trilogy, the Oresteia, and while it is tempting to consider the three plays as a unity it is equally valid to discuss them on their own. After all, every other surviving tragedy was once part of a trilogy, and the loss of its companion pieces is not considered an insuperable impediment to our studying it. In the case of Agamemnon, of course, the presence in the background of the other two plays enhances our knowledge, and our awareness of how the trilogy develops and ends adds to our appreciation of its beginning.

I first translated Agamemnon for performance (as a stand-alone play), which I directed for Actors of Dionysus in 1999. I directed a subsequent, very different production for the same company in 2003. Since then I have been fortunate to work on several of the speeches with Sian Philips, Stephen Greif and the late Fenella Fielding. Every actor who has performed my words has enhanced my understanding of the text, and my personal thanks go to them all.

Every chapter in this volume, too, has deepened my understanding and appreciation of the text and context of Agamemnon. The collection was assembled during the Covid-19 crisis of 2020, and my sincere thanks go to every contributor who, despite the many demands imposed upon them by having to revise courses for distance-learning, managed so determinedly to submit their chapters especially Edith Hall and Richard Seaford who, when two of their colleagues were forced to drop out because of illness or bereavement, stepped into the breach, adapting and updating material from lectures they had given in association with one of my productions of the play.

As with other volumes in this series, I have allowed authors to choose those aspects of the play on which they wished to focus. Inevitably there is the occasional small overlap between some chapters, with which I have not interfered, and, while I suggested that authors use the forms BC and AD , I respected the wishes of those for whom it was important to use BCE and CE . Equally, I have respected contributors choices with regard to transliteration from the Greek and spelling of names, e.g. Clytemnestra / Clytaemestra.

Many of the quotations from Agamemnon are taken from my own translation (a slightly revised version of my 1999 version), which is printed after the chapters. Readers wishing to use it for productions of their own should contact me through my website, www.davidstuttard.com, where applications for performance should be made before the commencement of any rehearsals.

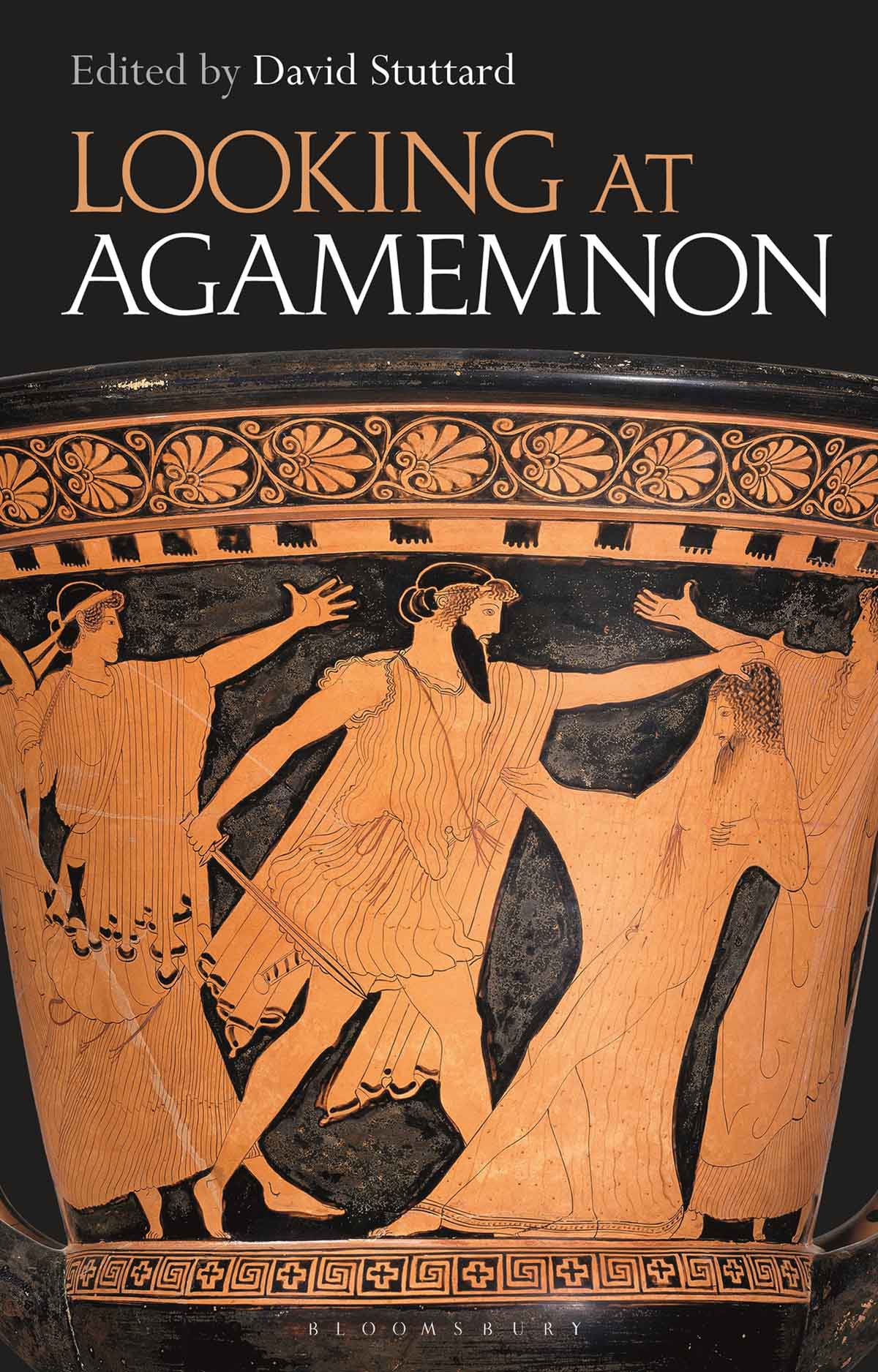

Finally, I would like to thank all those who have been involved in the production of this book, especially the twelve Olympian contributors, who have given so generously of their time, and with whom it has been such a pleasure to work. At Bloomsbury, my thanks go to Alice Wright, who commissioned it, her maternity-leave replacement, Georgina Leighton, and her assistant Lily MacMahon; also to Rachel Walker, the Senior Production Editor, Dave Cummings, who edited the text and Terry Woodley, who designed the cover; also to the ever-efficient Merv Honeywood, the Client Manager at RefineCatch. A very big thank you, too, to the home team, my wife Emily Jane (not yet quite so frustrated by my endless forays into the classical world that she has been driven to emulate Clytemnestra) and my research assistants, our two cats, Stanley and Oliver, lion-cubs reared in the palace, but thankfully (so far) with a better outcome than that imagined by the chorus in Agamemnon.

Agamemnon is at heart a revenge play. On the face of it the plot is simple: it tells how Queen Clytemnestra of Argos murders her husband, Agamemnon, leader of the Greek army in the Trojan War, in vengeance because he killed their daughter. But there is nothing simple in how Aeschylus handles his material. As the drama unfolds and we delve deeper into the circumstances that have led to this moment, the reasons why Agamemnon apparently must die become increasingly more complex: motive piles on motive as more and more characters, both human and divine, become implicated in the litany of savagery that plagues the royal palace, until the very building appears to assume a malignant life of its own. Yet this is no mere horror story. While Agamemnons palace, with its slaughtered children, gushing blood and vengeful furies that at times seem to possess Clytemnestra, may share similarities with the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubricks film, The Shining, in Aeschylus hands the atrocities perpetrated by its inhabitants become the starting point for a profound meditation on the nature of crime and punishment, innocence and guilt, vengeance, justice, good government and the relationship between humankind, the gods and the world around them, overarching themes that will permeate the whole of the Oresteia trilogy of which Agamemnon forms the first part.

However, while the themes are universal and the tragedy may in many ways be timeless, Agamemnon was very much a product of its age, so to begin to appreciate it fully we must be aware of the social, cultural and political conditions familiar to Aeschylus and his audience in the Athens of 458 BC , when it was first staged. Not that this was its only performance: so popular was the Oresteia that it was often revived including by Aeschylus himself in Sicily, and after his death by his successors in Athens and elsewhere while today it enjoys the distinction of being the only classical Greek trilogy to survive (almost) complete. Considerations of context as well as of why Agamemnon has intrigued so many for so long are the subject of many of the chapters in this book. But before we begin to examine the play in depth, it might perhaps be useful not only to set it in its historical and cultural context but to consider briefly the process of translating the text into English. And, because the first audience was more familiar with the mythological background to the play than many of us are today, it is with this that we shall begin.

Next page