Publication of this book has been made possible, in part, through support from the Anonymous Fund of the College of Letters and Science at the University of WisconsinMadison and the generous support and enduring vision of Warren G. Moon. The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WC2E 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com Copyright 2018

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to . Printed in the United States of America This book may be available in a digital edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aeschylus, author. | Mulroy, David D., 1943 translator, writer of supplementary textual content. | Container of (expression): Aeschylus. Agamemnon. English. Choephori. English. | Container of (expression): Aeschylus. Eumenides. Eumenides.

English.

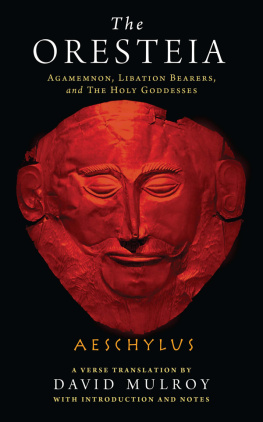

Title: The Oresteia: agamemnon, libation bearers, and the holy goddesses / a verse translation by David Mulroy, with introduction and notes.

Other titles: Oresteia. English | Wisconsin studies in classics.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin : The University of Wisconsin Press, [2018] | Series: Wisconsin studies in classics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017044983| ISBN 9780299315603 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780299315641 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: AeschylusTranslations into English. | Agamemnon, King of Mycenae (Mythological character)Drama. | Orestes, King of Argos (Mythological character)Drama. | LCGFT: Tragedies (Drama)

Classification: LCC PA3827.A7 M77 2018 | DDC 882/.01dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017044983 ISBN-13: 978-0-299-31568-9 (electronic) For Richard W. | LCGFT: Tragedies (Drama)

Classification: LCC PA3827.A7 M77 2018 | DDC 882/.01dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017044983 ISBN-13: 978-0-299-31568-9 (electronic) For Richard W.

Johnston

Preface

This volume contains my translations of the three plays constituting Aeschylus

Oresteia:

Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and

Eumenides. The University of Wisconsin Press published

Agamemnon separately in 2016 since that play is often read and taught independently, in world literature classes, for example, as an example of the best of classical Greek tragedy. Yet

Libation Bearers and

Eumenides are not devoid of interestfar from it. Read by itself,

Agamemnon is about individuals struggling in vain to escape the consequences of their evil acts. In

Libation Bearers and

Eumenides, Aeschylus widens his view and strikes a hopeful note. Athens, personified by the goddess Athena, replaces Orestes as the real hero.

Aeschylus implies that the democratic city-state alone has mastered the tools needed to resolve the conflicts that arise where ties of blood are all that count: persuasion instead of compulsion; disinterested reasoning instead of blind loyalties. The theme is nothing if not timely. I have recently been won over to the view that the third play of the trilogy should be called The Holy Goddesses or The Furies, not Eumenides (see ), although I employ Eumenides as the title in my discussion of other aspects of the trilogy to avoid confusion. Two items in my lists of characters may confuse some readers. First, Coryphaeus. This is just an ancient Greek word meaning head in the sense of chief or leader.

In the context ofGreek tragedy, it denotes the leader of the chorus, who shared its attributes. He played an old soldier in Agamemnon, an elderly slave woman in Libation Bearers, and a Fury in Eumenides, but he had an additional function. Besides singing and dancing, he could and did converse with the actors. Second, despite what you may have seen in other translations (including my Agamemnon), the correct spelling of Mrs. Agamemnons name is Clytaemestra (), not Clytemnestra. The former spelling is found in the most ancient evidence, such as inscriptions on Athenian pottery.

The n is thought to have been introduced by Byzantine scholars on the mistaken assumption that her name was a play on the verb mnaomai (to court or woo). The other root involved in the names supposed etymology was klyto- (famous orin Clytaemestras caseinfamous). In preparing this translation, I relied chiefly on Alan Sommersteins Loeb Library Oresteia for help in resolving textual and interpretive issues. In addition, I regularly consulted Taplins Stagecraft of Aeschylus, Raeburn and Thomass commentary on Agamemnon, Garvies commentary on Choephori, and Podleckis on Eumenides. All translations are mine. Cf. Alan H. Alan H.

Sommerstein, Aeschylus, Oresteia, x n4; Eduard Fraenkel, ed., Aeschylus: Agamemnon, commentary on line 84.

Introduction

I maintain that Aeschylusand not, as some say, Euripidesfirst introduced the spectacle of drunken characters in tragedy. In the

Cabiri he depicts Jasons comrades drunk. In other words, he attributes to his heroes what he himself did as a tragic dramatist: he composed his tragedies while drunk. ATHENAEUS 10.428 At the great annual springtime festival of Dionysus in ancient Athens, three tragic poets competed against each other. Each presented a set of three original tragedies and a farcical satyr play.

First performed in the spring of 458 BCE, Aeschylus Oresteia won the first prize then. It has the distinction now of being the only complete dramatic trilogy to have been preserved. Its three tragedies are entitled Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and Eumenides. The Oresteia tells the story of Orestes. He is the son of King Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks attack on Troy. When Agamemnon returns from the war, he is murdered by his faithless wife, Clytaemestra.

Through his oracle, the god Apollo tells Orestes that he must avenge his father by killing his mother and her lover. Having done so, the youth is pursued by theFuries, horrible underworld goddesses who punish those who murder blood relatives. He flees to Athens, where the goddess Athena establishes a court that tries Orestes and finds him guiltless. She placates the Furies, who become benevolent goddesses dwelling under the ground in Athens. The friendship between Athena and the Furies stands for the reconciliation of two religious dispensations that competed for influence in classical Athens. The more primitive rites focused on the spirits of the dead and the need to win and keep their good will.

Generations of the living and the dead were bound to each other through the indissoluble ties of blood. Sons were punished for the sins of their fathers. The worship of Zeus and the other Olympians was infused with a different spirit. Their rituals celebrated the good things of life, including song and dance, and were intertwined with the government of the polis, which made the good life possible. A persons service to the city was more important than the identity of his ancestors. Through the taming of the Furies, the Oresteia suggests that ties of blood should play an important but subordinate role in the life of an enlightened community.