AESCHYLUS (525 BC456 BC), the first of ancient Greeces major dramatists, is considered the father of Greek tragedy. He is said to have been the author of as many as ninety plays, of which seven survive. JOEL AGEE is a writer and translator. He has received several prizes, including the Berlin Prize of the American Academy in Berlin in 2008 and the Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize for his translation of Heinrich von Kleists verse play

Penthesilea. He is the author of two memoirs

Twelve Years: An American Boyhood in East Germany and

In the House of My Fear. His translation of

Prometheus Bound was produced at the Getty Villa in 2013.

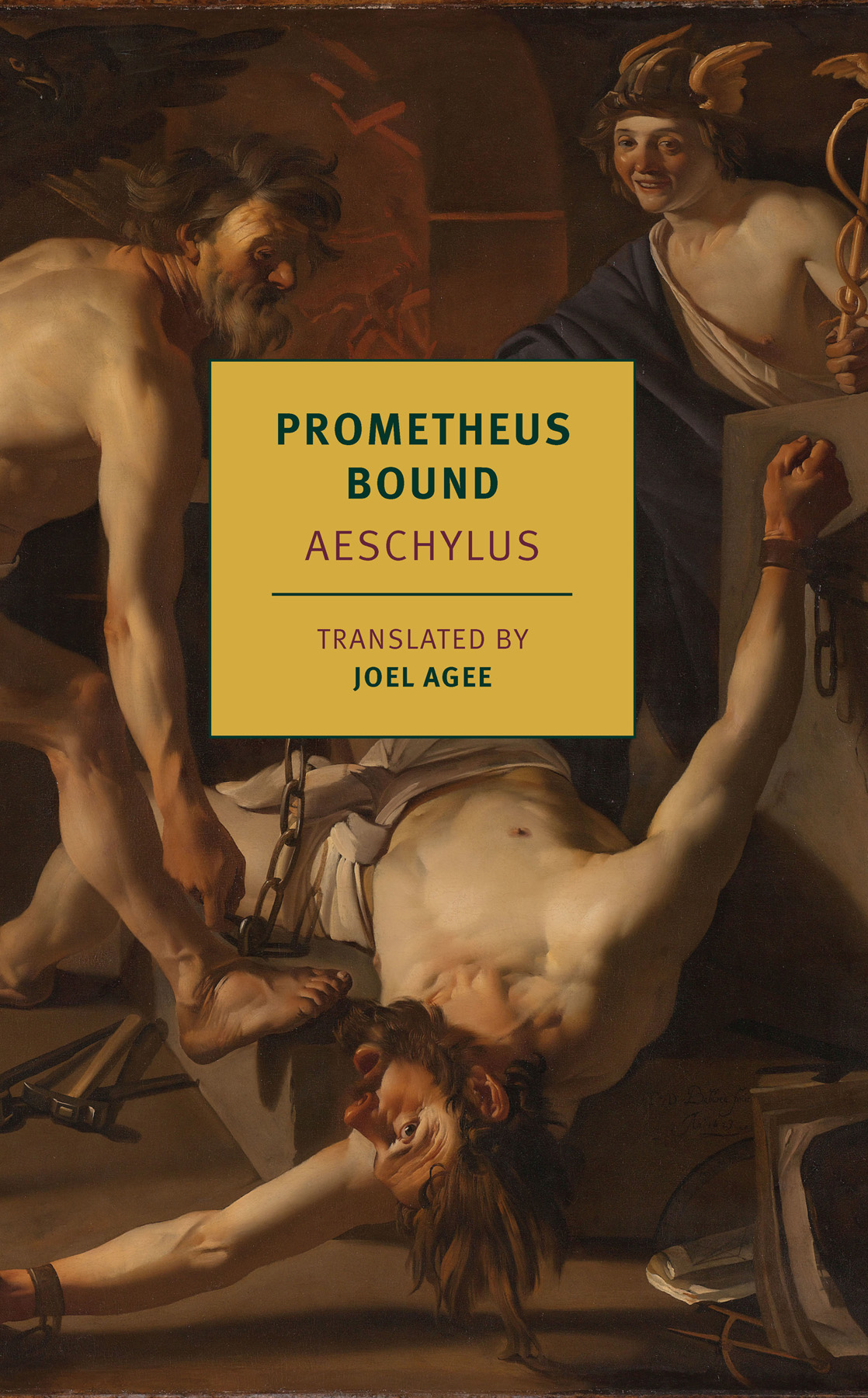

He lives in Brooklyn, New York. PROMETHEUS BOUND AESCHYLUS Translated and with an introduction by JOEL AGEE NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS  New York This translation of Prometheus Bound was commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the CalArts Center for New Performance, and Trans Arts. This play was first performed in the Getty Villas Outdoor Classical Theater from August 29 to September 28, 2013. THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2014 by Joel Agee All rights reserved. Cover illustration: Dirck van Baburen, Prometheus Chained by Vulcan, 1623; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aeschylus, author. [Prometheus bound.

New York This translation of Prometheus Bound was commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the CalArts Center for New Performance, and Trans Arts. This play was first performed in the Getty Villas Outdoor Classical Theater from August 29 to September 28, 2013. THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2014 by Joel Agee All rights reserved. Cover illustration: Dirck van Baburen, Prometheus Chained by Vulcan, 1623; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aeschylus, author. [Prometheus bound.

English] Prometheus bound / by Aeschylus ; translated and with an introduction by Joel Agee. 1 online resource. (New York Review Books classics) ISBN 978-1-59017-861-4() ISBN 978-1-59017-860-7 (alk. paper) I. Agee, Joel, translator. Title. III. III.

Series: New York Review Books classics. PA3827.P8 882'.01dc23 2014043761 ISBN 978-1-59017-861-4 v1.0 For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014. CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

FEW GODS or monsters in the teeming world of Greek mythology have ignited the Western imagination like Prometheus, the Titan who was cruelly punished for stealing fire from the gods and giving it to man. Nietzsche saw in him the prototype of the artist, the great genius for whom even eternal suffering is a slight price. Percy Bysshe Shelley portrayed him in his masterwork,

Prometheus Unbound, as the champion of mankind against all manner of tyranny, celestial and mundane. Mary Shelleys

Frankenstein, a more pessimistic treatment of the theme, was subtitled The Modern Prometheus.

Beethoven associated the Titan with his own revolutionary ideals in the ballet music for The Creatures of Prometheus and the Prometheus Variations for pianoforte that developed from it. His Eroica, too, originally titled the Bonaparte, was inspired by a vision of Napoleon as the Promethean hero of the age. Messianic ideologies and liberationist movements adopted Prometheus as well. The Polish nationalist struggle initiated by Jzef Pisudski, for instance, was named Prometheism. More recently, the short-lived German Democratic Republic, where I lived as a child and teenager, elected Prometheus as its galleon figure.[] That idea probably derived from Karl Marxs lifelong fondness for Prometheus as an archetype of revolutionary will. Already in his doctoral dissertation of 1841, he had called him the loftiest saint and martyr in the philosophical calendar.

That was not mere youthful romanticism. A quarter of a century later, Prometheus appears in Das Kapital (in chapter 13) as an emblem of the proletariat chained to capital. There have also been conservative and authoritarian interpretations. The political philosopher Eric Voegelin regarded Prometheus as a symbol of the demonic drive of human existence in its self-assertion and expansiveness,[] There were several treatments of the theme in the ancient world. The most complete and lastingly famous one that survived was Prometheus Bound. Throughout antiquity and for centuries after, the tragedy was universally attributed to Aeschylus (525456 BC).

The scholars of the Great Library of Alexandria deemed him the author of the play. Various classical authors referred to him as such. No one thought of questioning tradition and ancient authority until the mid-nineteenth century, when scholars began to raise doubts about the portrayal of Zeus in Prometheus Bound. How could the pious author of Agamemnon or The Suppliant Maidens have portrayed the King of kings as an unjust and ruthless despot? This objection was met with the argument that the play was but the first (or, some thought, the second) movement in a trilogy, and that the whole work described an evolutionary arc that would culminate in the release of a chastened Prometheus by a matured and compassionate Zeus. Such a story line, enriched and complicated, of course, by a wealth of dramatic development, could indeed be constructed out of the surviving fragments of two other playsPrometheus Unbound and Prometheus the Firebringerthat were traditionally ascribed to Aeschylus.[] But this theory was not unassailable. Was an evolving Zeus, let alone a Zeus in need of character reformation, even conceivable in the fifth century BC? Was the trilogy therefore not probably the work of a later author? That contention, in turn, was rebutted with instances of divine personages in plays by Aeschylus who do change and develop.

Claims and counterclaims mounted into a complicated debate over the Zeus problem in Aeschylus that went on for decades. Eventually metrical and stylistic analyses were brought to bear, both against and in support of the plays authenticity. Today, many classical scholars reject the traditional attribution of the play to Aeschylus. Others still favor the verdict of antiquity. There is simply not enough evidence to decide the matter one way or the other. The conventional ascription to Aeschylus is still in use.

The word drama, in Greek, means action, and action, in modern theatrical practice, is generally understood to mean the physical accomplishment of a characters intentions. Little of the sort seems to be happening in Prometheus Bound. One man, a sort of demigod at that, chained to a rock, orated to, and orating at, a sequence of embodied apparitions. That is how Robert Lowell, in a prefatory note to his translation of Prometheus Bound, summed up the play. Little wonder that he considered it the most undramatic of the Greek classical tragedies. He was not alone in this opinion.

The play has long had the reputation of being extremely static and therefore all but impossible to stage. But speech is action, and this is the case not only on the theatrical stage but also in life, and particularly in the political life of fifth-century Athens. There, according to Hannah Arendt, speech and action were considered to be coeval and coequal, meaning not only that most political action is transacted in words, but more fundamentally that finding the right words at the right moment, quite apart from the information or communication they may convey, is action. For that reason, the polis was the most talkative of all bodies politic.[] Prometheus Bound is, like all Greek tragedy, a political as well as a religious play. Its action consists in an ardent, protracted dispute among several characters, all but one of them immortal, who find themselves pitted between two diametrically opposed conceptions of social order: on the one hand the self-legitimizing ethos of tyrannical power, and on the other the idea of a standard of justice that is binding on rulers and ruled alike. It is not an abstract battle of words.

New York This translation of Prometheus Bound was commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the CalArts Center for New Performance, and Trans Arts. This play was first performed in the Getty Villas Outdoor Classical Theater from August 29 to September 28, 2013. THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2014 by Joel Agee All rights reserved. Cover illustration: Dirck van Baburen, Prometheus Chained by Vulcan, 1623; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aeschylus, author. [Prometheus bound.

New York This translation of Prometheus Bound was commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the CalArts Center for New Performance, and Trans Arts. This play was first performed in the Getty Villas Outdoor Classical Theater from August 29 to September 28, 2013. THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2014 by Joel Agee All rights reserved. Cover illustration: Dirck van Baburen, Prometheus Chained by Vulcan, 1623; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aeschylus, author. [Prometheus bound.