Contents

Guide

Page List

ALSO BY OLIVER TAPLIN

The Stagecraft of AeschylusGreek Tragedy in ActionGreek FireHomeric SoundingsComic AngelsPots and PlaysTHE ORESTEIA

AGAMEMNON | WOMEN AT THE GRAVESIDE | ORESTES AT ATHENS AESCHYLUS A NEW TRANSLATION BY OLIVER TAPLIN

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923 NEW YORK LONDON Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. Copyright 2018 by Oliver Taplin All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W.

Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830 Book design by Chris Welch Production manager: Lauren Abbate JACKET DESIGN BY KATHLEEN LYNCH / BLACK KAT DESIGN JACKET ILLUSTRATION: ORESTAS PURSUED BY THE FURIES, 1795 (ENGRAVING), FLAXMAN, JOHN (17551826) / PRIVATE COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES ISBN 978-1-63149-466-6 ISBN 978-1-63149-467-3 (e-book) Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www.wwnorton.com W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS In gratitude to the poets I have had the good fortune to know

CONTENTS

Publishers Note: On older legacy e-readers, line numbers will flow into the lines of poetry, instead of appearing off to the side.

Please do not treat these numbers as part of the text. We apologize for the inconvenience.

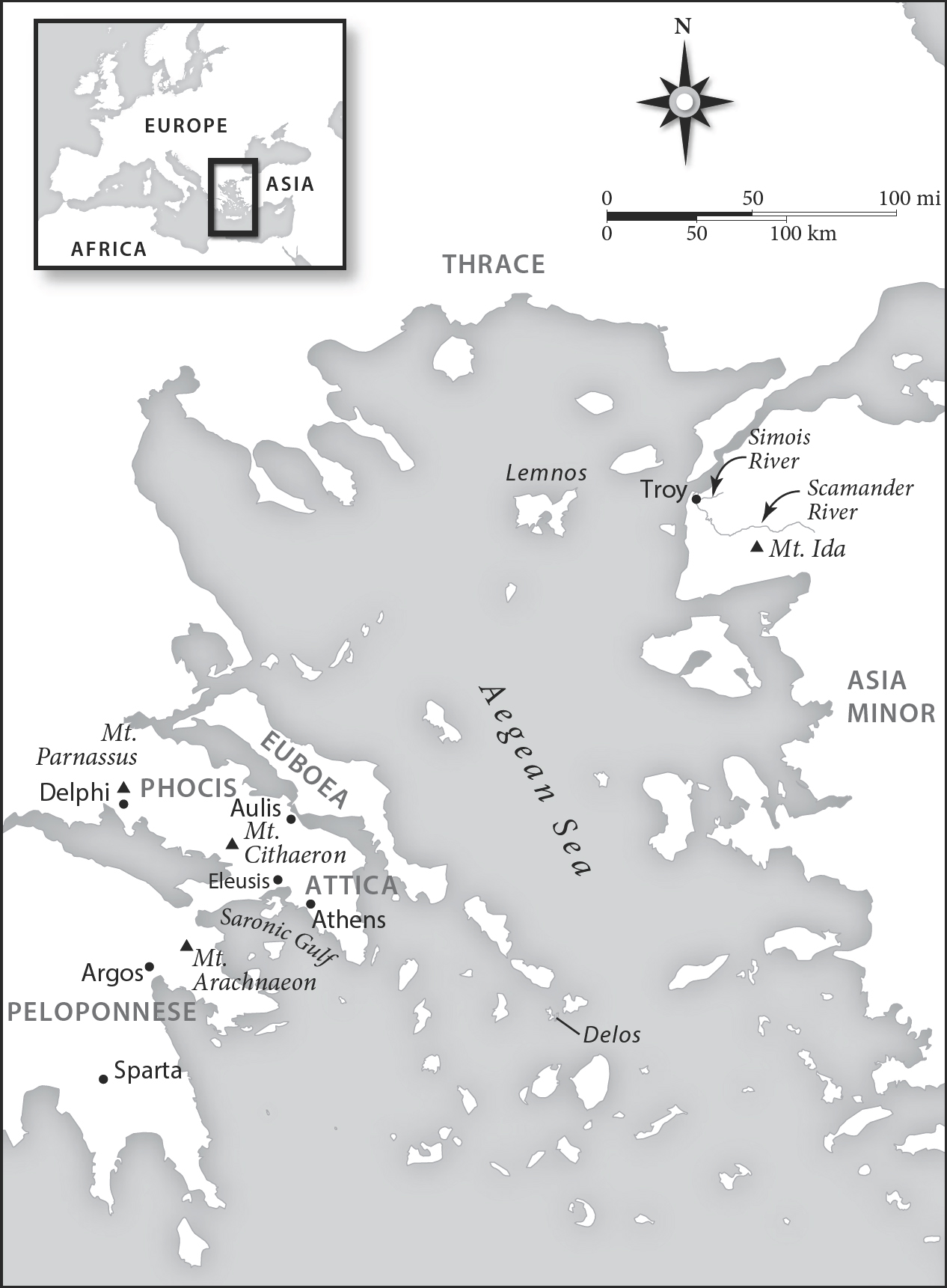

Map by Mapping Specialists, Ltd., Fitchburg, WI.

Popular Performance

T he

Oresteia trilogy was created by Aeschylus to be performed in the open air before his fellow citizens in Athens on a spring day in 458 B.C.E. Although it comes from so early in the record of world literature, it retains an extraordinary power to grip and to provoke to this day. In fact, it is probably more widely known and widely performed now than at any other time in the last twenty-two hundred years. It remains a challenging yet accessible work which embodies conflicts about family, gender, and justice in ways that still arouse disturbing thoughts and strong emotions.

The Oresteia was notand is notjust a text: Aeschylus was the director, composer, and choreographer as well as the playwright and poet. The text in this volume is the verbal record, the libretto, of a work of art that interwove action, costume, objects, dance, music, poetry, and voice. Furthermore, it did not come into being for an exclusive or elite publicand there is no good reason why it should be regarded like that today, either. It was produced, on the contrary, for an audience of at least six thousand, quite possibly many more, gathered in the theatron, the viewing place dedicated to honor the god Dionysus, beneath the walls of the Athenian Acropolis. It was a huge event, the popular entertainment of its time. This is all a far cry from most modern theatrical experiences, which are constrained within enclosed, darkened spaces where actors move naturalistically and speak colloquial prose.

Also, as well as the actors, there was the chorus, which provided an essential layer in Greek drama. Many modern productions have found that, far from being a problem, this group of witnesses, with their searching attempts to make some sense of the tragedy through their poetry and music, supply an extra, vivid dimension. This is especially true of Aeschylus plays, where the choral songs (or odes) are so strong and full. It makes sense that Richard Wagner, with his ideas of a total artwork (Gesamtkunstwerk), said that his impressions of the Oresteia molded his ideas about the whole significance of the drama and of theater. More recently, many of the leading stage directors have seized the opportunity to put on Agamemnon or the whole trilogy in order to push the boundaries of routine theater. A roll call of names gives some idea of their variety: Max Reinhardt, Jean-Louis Barrault, Tyrone Guthrie, Vittorio Gassman, Karolos Koun, Peter Stein, Peter Hall, Ariane Mnouchkine, Katie Mitchell, Michael Thalheimer.

These productions have not been acts of antiquarian piety to make passive audiences feel complacent; they have been innovative explorations to provoke those who want to have their ears and eyes and emotions freshly opened. So where did this story of theatrical revolution begin? Aeschylus was born in about 525 b.c.e., and the Oresteia, put on in 458, just two years before his death, was recognized as his masterpiece. The art form of tragedy had developed with amazing rapidity, given that theater, in the core sense of the word, had most probably been invented within Aeschylus lifetime. For theater to happen, there had to be a fixed viewing place (theatron) and a fixed time for the audience to gather; and rehearsed players, both actors and chorus, had to be organized to enact a structured story. The evidence all suggests (though not beyond dispute) that these conditions coalesced not long before 500 b.c.e. It can hardly be coincidence that at just that same time, in 508, the Athenians radically changed their political constitution to transfer ultimate power to the people (demos)in other words, they inaugurated the worlds first democracy.

So the first performance of the Oresteia may well mark the fiftieth birthday both of democracy and of theater. The Athenian theatron was inherently democratic, in that it was not select or exclusive: every citizen was admitted, and the seating was not segregated or privileged. Furthermore, tragedy calls for understanding and sympathetic fellow feeling toward the situations and sufferings of other, very different people; and a thoroughgoing democracy arguably calls for an enhanced sense of the variousness of humanity and of human suffering. Open-mindedness and a plurality of viewpoints are needed if true participation in any society is to become extended to all its citizens. This is epitomized in the third play of the Oresteia, where the vendetta vengeance of the old aristocratic society, structured around family bonds, as seen in the first two plays, is superseded by the jury made up of citizens. This civic institution hands adjudication over to society as a whole, subsuming all other affiliations.

The theater was open, then, to all citizens. But did that extend to women, who were citizens in only limited ways that did not include participation in political decision-making or legal proceedings? Scholars are divided on this question of whether there were women present in the audience or notthere seems to be good evidence both for and against. But if they were admitted, they were still very probably a marginal minority. In that case, it is fascinating that women are so central to so many ancient Greek tragedies, not least the Oresteia, where Clytemnestra and Cassandra are in many ways more powerful and intelligent figures that any of the male characters. Outside of the theater, women were restricted and suppressed, but inside that contained space the plays opened up a different perspective: the realization of their potential, their strengths and their articulacy. Clytemnestra and her tragic sisters may be portrayed as deviant and dangerous, and they ultimately come to grief, but the idea that women are far more

AGAMEMNON | WOMEN AT THE GRAVESIDE | ORESTES AT ATHENS AESCHYLUS A NEW TRANSLATION BY OLIVER TAPLIN

AGAMEMNON | WOMEN AT THE GRAVESIDE | ORESTES AT ATHENS AESCHYLUS A NEW TRANSLATION BY OLIVER TAPLIN  LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY Independent Publishers Since 1923 NEW YORK LONDON Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. Copyright 2018 by Oliver Taplin All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W.

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION A DIVISION OF W. W. NORTON & COMPANY Independent Publishers Since 1923 NEW YORK LONDON Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. Copyright 2018 by Oliver Taplin All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W.