Table of Contents

Praise for The Braided River

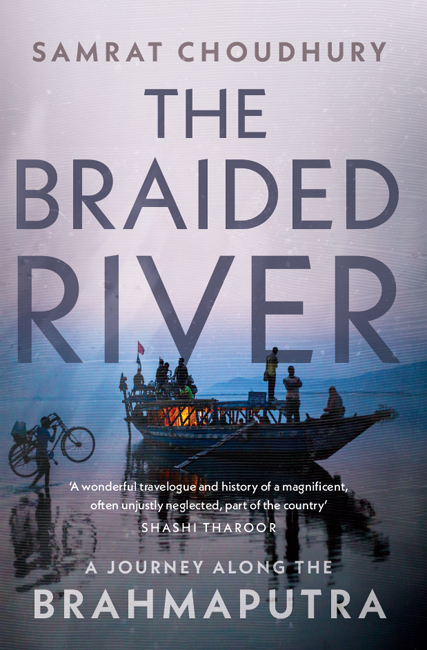

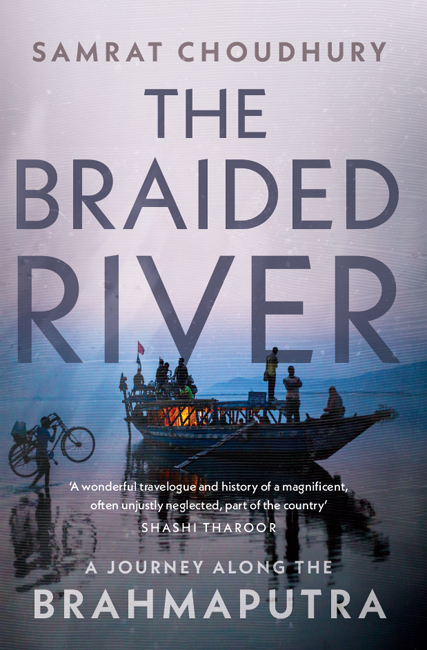

Samrat Choudhurys tale of a journey on the Brahmaputra is a wonderful travelogue and history of a magnificent, often unjustly neglected, part of the country. Filled with rich imagery and speckled with deft touches of humour, Choudhury brings to life both the powerful river and those who made their lives along its banks. Dr Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament and author

A scholarly and delightfully diverting journey of cultural and geographical exploration down one of the worlds most important yet least-known rivers. Victor Mallet, author of River of Life, River of Death

Meticulously researched yet very readable, this superb travelogue braids diverse experiences and observations together with vivid descriptions, reflections and humour, as the writer journeys through the waterways, valleys and mountains around one of the worlds greatest river systems. A must-read. Mitra Phukan, novelist, translator and columnist

Samrat Choudhury recounts the Brahmaputras epic tale in a many-layered travel memoir that includes personal observations and encounters, history, geography, folklore and mythology. Each strand is deftly plaited into a compelling narrative that reveals the great rivers vast breadth and length, as well as its hidden depths. Stephen Alter, author of Wild Himalaya

This book is dedicated to the last remaining free-flowing rivers of the world, and to all who love them

Contents

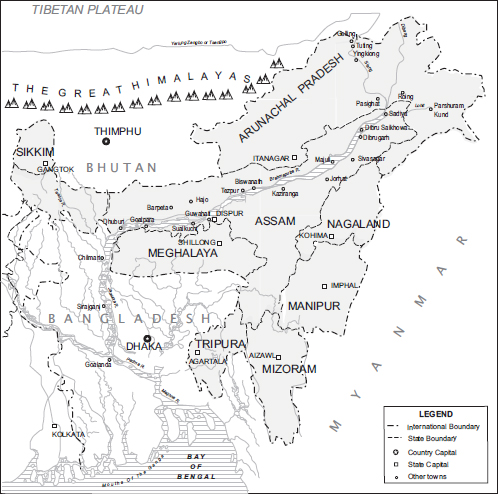

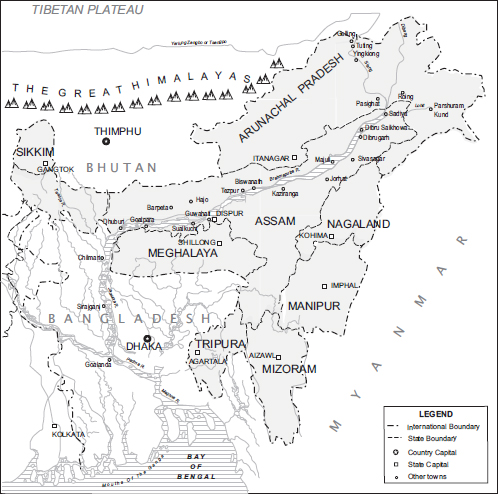

Map by Nitendra B. Srivastava

This map is for representational purposes only and does not purport to depict political boundaries.

I T WAS ALWAYS THERE, a near and distant reality. My first memories of it are of the chugging sound of the old train with its smoky diesel engine changing into a loud clanging as it crossed the old iron bridge near Guwahati. It was a thrill to look out and see the swirling waters below more water than I had ever seen in my brief life until then, because I had not seen the sea. The clanging went on for a marvellously long time. People would rush to the windows and even to the open doors, and thrillingly fling coins into the river. Sometimes I was given a ten- or twenty-paisa coin to throw in too. It was an offering to Brahmaputra the river god, the son of Brahma and meagre and mindless as it was, it was good sport; a grudging attempt at the appeasement of a force of nature whose might, even to a mere child of six or seven, was apparent.

As I grew older, I became aware of other things about the river, from my distant perch because that was how it felt 101 km away in the hill town of Shillong. There was the time a relative who owned a gramophone player got hold of an old vinyl record of songs by Bhupen Hazarika. The delight of the moment when I first heard his clear, mellifluous voice has stayed with me. It was a delight that brought confusion with it. I heard the classic Bistirno Duparer, set to the tune of Old Man River, in Bengali, with the Ganga as the subject. A couple of years later, in Guwahati, where my fathers elder brother who worked in the Brahmaputra Board lived, I heard the same song in Assamese in its avatar as Bistirno Parore with Burha Luit as the subject. I was confused. I didnt understand many of the words. And there was the Brahmaputra, and the Burha Luit, and the Ganga were they all the same? Was the Burha Luit, perhaps, both Ganga and Brahmaputra?

Once I wandered along the riverside with an older neighbour. The river was right there, vast, swirling. Adventure beckoned. The neighbour, who was a college student at the time and had some pocket money, marched down to the ghat and struck a deal with a boatman. He would row us out in his motorless wooden boat towards the river island of Umananda, visible nearby.

It was only a short distance but it felt like an epic voyage. I had by then learnt to row, but rowing in the calm waters of Wards Lake in Shillong was one thing and in the Brahmaputra was quite another. The wooden oar itself was too heavy for me. I still remember the boatman talking about underwater currents that sucked away unsuspecting people to their riverine graves.

Vague familiarity and a distant curiosity about the river were all I had when I left Shillong for college. Going off on quests was what people in books written by rich people with social security or trust funds did. I loved those stories, but staying alive and earning a living were the quests that I had been brought up to understand as real. Indias Northeast in the 1980s and early 1990s was a troubled place. Insurgencies were everywhere, and riots were frequent. The army and paramilitary forces patrolled the streets in armoured vehicles. There were soldiers behind sandbags with machine guns at important places. The news was full of killing and dying.

I studied engineering. The plan was to get an MBA or take the GRE exam and escape to some place where there were no riots and insurgencies, things worked as they were supposed to, and people made a comfortable living. Thats how it might have gone, but life had other plans. A series of events, some pure chance, saw me become a journalist instead. At first it was exciting enough, but in time the groove became a bit of a rut. It became a routine, which included in dollops the staples of office drudge work. In addition, there was the growing realization that my job was basically to ensure that the paper was run on a shoestring budget with minimal staff and resources, and came out on time with as few spelling and grammatical errors as possible. Not having the same stories as every other newspaper could get me into trouble; on the other hand, having an exclusive story that rocked the wrong boat could also do the same.

An old dream to live life as a writer came back. I had already written and published a novel in the midst of a demanding and stressful day job. I could not afford non-fiction. That required research, travel and free time, for which I had neither the budget nor the freedom. I might have continued with my comfortable Mumbai life if an invitation from Sanjoy Hazarika, who was then heading the Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research in Jamia Millia Islamia, hadnt landed in my inbox. On a whim, I bought a ticket, took two days off from work and went to Delhi to attend a conference where I was not even presenting a paper. During a tea break, a chance conversation led to the question: Would I like to write a book on the Brahmaputra?

It would involve going on an epic journey. The trouble was, I was living in Mumbai and had a job there. To go anywhere in the Brahmaputra Valley I would have to travel at the very least to Guwahati, more than 2,000 km east. From there, I would have to make long and potentially difficult journeys by road and river. I could not afford to quit my salaried job, and getting a long sabbatical from work was out of the question. Nor could I afford the luxury of hiring cars and boats to go the entire, and quite considerable, length of the river. The sensible thing to do, it seemed, was to say no.

So I did what anyone in such a situation ought to do I said yes without sweating the details, and plunged right in.

I T WAS AROUND 6 oclock on a grey morning, crack of dawn by our standards, when my photographer friend Akshay Mahajan and I sleepily made our way to Mumbais Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport for the flight to Dibrugarh in the eastern end of Assam to begin our journey. We had done a little homework, shopped for raincoats and hiking shoes, and stuffed sleeping bags into our backpacks, just in case. We were ready. The river was waiting, bright and clear on the map, a somewhat tasselled ribbon of blue winding its way down from well, somewhere around Dibru Saikhowa in Assam where three other ribbons of blue, representing the Siang (also known as Dihang), Lohit and Dibang, meet untidily to become the Brahmaputra. Its origins, according to all authorities, lie in Tibet, near Mount Kailash, at an altitude of around 5,150 m, where it starts life as the Yarlung Tsangpo. From there, it flows from west to east before making a U-turn and entering Arunachal Pradesh. There its name changes to Siang. The Siang then gathers more streams and flows down through the Arunachal hills towards the plains of Assam. At the foothills, it meets the Lohit and Dibang. Downstream of this confluence, it is the Brahmaputra. The Brahmaputra in turn flows through Assam, gathering yet more streams, before entering Bangladesh. Upon entering that country it undergoes one more change in nomenclature, this time accompanied by a sex change the male Brahmaputra, for some reason, becomes the female Jamuna. The Brahmaputra as Jamuna makes its way towards an eventual confluence with the Ganga, known in Bangladesh as the Padma. This great river of many great rivers finally flows into the Bay of Bengal, after undergoing yet another change of name as the Meghna. Its whole length is 2,880 km.