Charlie Porter

WHAT ARTISTS WEAR

About the Author

Charlie Porter is a writer, fashion critic and art curator, and visiting lecturer in Fashion at the University of Westminster. He has contributed to titles such as the Financial Times, Guardian, New York Times, GQ, Luncheon, i-D and Fantastic Man, and has been described as one of the most influential fashion journalists of his time. He was a juror for the Turner Prize in 2019, and lives in London.

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Penguin Books 2021

Text copyright Charlie Porter, 2021

Modern Studies by Charlotte Prodger.

Text Charlotte Prodger 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover photograph by Gavin Ashworth of Georgia OKeeffes Emsley Suit, 2016.

Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton. Georgia OKeeffe Museum.

[2000.3.386]. Courtesy of Georgia OKeeffe Museum.

ISBN: 978-0-141-99126-9

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

On a Wednesday evening in May, the Tate threw a cocktail party in Venice. It was the opening week of the Biennale, the festival of international art held in the city every other year. The gathering was at Scuola Grande di San Rocco, its walls and ceilings covered with vast paintings by the sixteenth-century artist Tintoretto. The invitation read: Dress code: Lounge suit.

According to Debretts, advisers on etiquette, a lounge suit is, for men, a suit worn with shirt and tie. For women, a smart, or cocktail, dress (with sleeves or a jacket).

Down the front, there were formal speeches from the gallerys chairman and director. At the back of the hall stood Charlotte Prodger in a long-sleeved white T-shirt. Five months earlier, Prodger had won the Turner Prize. Organized by the Tate, it is one of the most prestigious prizes in art.

Nearby was Helen Marten, another previous winner. She wore a black trench coat, a white shirt and blue utility pants. Her partner, Magali Reus, a recent nominee for the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture, was wearing a silk shirt, jeans and sneakers.

The artist Anthea Hamilton, once a Turner nominee, arrived in a tiered and sequined dress that you would not call smart, or cocktail: she later described it as Edwardian. She wore it with sneakers and, because it was pouring with rain outside, an overcoat. Stood a few feet away was Helen Cammock, one of that years Turner nominees. Cammock was wearing a grey T-shirt and trackpants. On her feet were sneakers.

These five women are among the most vital artists of our time. Most of them are queer. Each lives and makes work within a patriarchal society and art world. They are supposed to play along with its structures, even if their work pushes against them. Clothing makes this tension abundantly clear.

If we were to look back at the clothes artists have worn over past decades, what might we learn about the conditions in which they made their work? What might an artists wardrobe say about their bravery and defiance, or indeed their compliance with the culture and ideology of their society? We might go a step further, look at our own wardrobe and ask: what might this then say about our own defiance or compliance?

Our clothing is an unspoken language that tells stories of our selves. What you are wearing right now is sending messages about who you are, what you think, and how you feel. This goes beyond the limitations of fashion: it is a daily, even hourly, signalling of our beliefs, emotions, intentions. Much of it is intuitive: we sharpen up to impress; cocoon ourselves when were feeling blue; make an effort on a date. But when we put on our clothes, we dont fully acknowledge their loaded meaning. We just wear them.

Many of us make daily compromises when we get dressed to go to work. Our clothing then carries other social meanings: power and ambition or acquiescence, humility or arrogance, repression and exploitation. For women, dressing for work presents a tougher challenge than it does for men.

Artists live a different way. The work of an artist is not office based. It breaks from the rhythm of 9 to 5, weekdays and weekends. It is a continual push for self-expression. Artists create their own circumstances, their studios becoming self-contained worlds. Their work can question, or it can reinforce, generally accepted ways of being. What artists wear can be a tool in their practice. Their clothing can tell of their desire for another mode of living or, sometimes, their conscious subscription to the status quo.

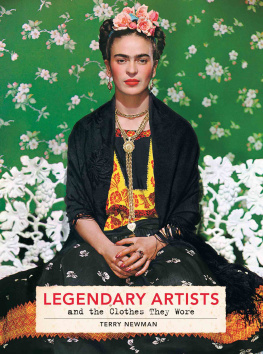

Artists are often revered for their style. I have friends who pin photographs of artists around their mirrors as inspirationsnapshots of Georgia OKeeffe, Barbara Hepworth. Fashion houses regularly plunder these images, copying their outfits as part of the relentless fashion-season cycle. It seems logical that an artist should have an eye for clothing, connected with the visual creativity of their work. When we really look at images of artists, we realize it goes deeper than that. There is more to what artists wear than just an appreciable way with clothing.

To approach an artist just as a style icon can strip away the reality of their life and work. Art isnt easy. It can be a lonely pursuit. Countless artists are ignored, acknowledged late in lives, or even only after their death. For many, their work is necessarily more important than recognition. Evidence of this sense of purpose, despite it all, is also found in their clothing. What they wear is testament to this fearlessness, this focus.

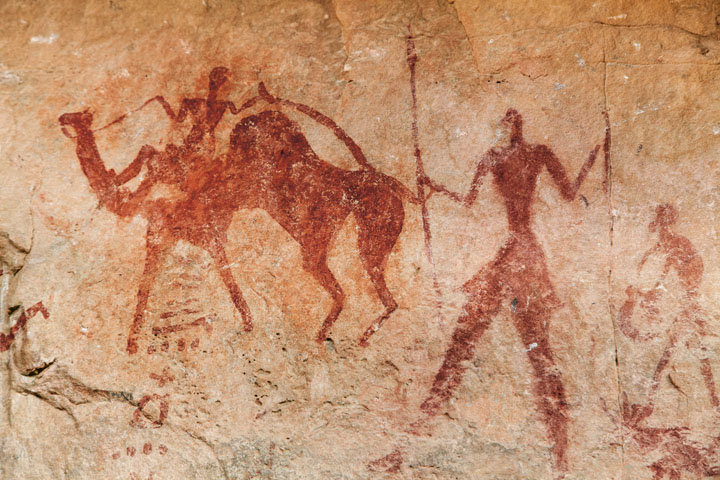

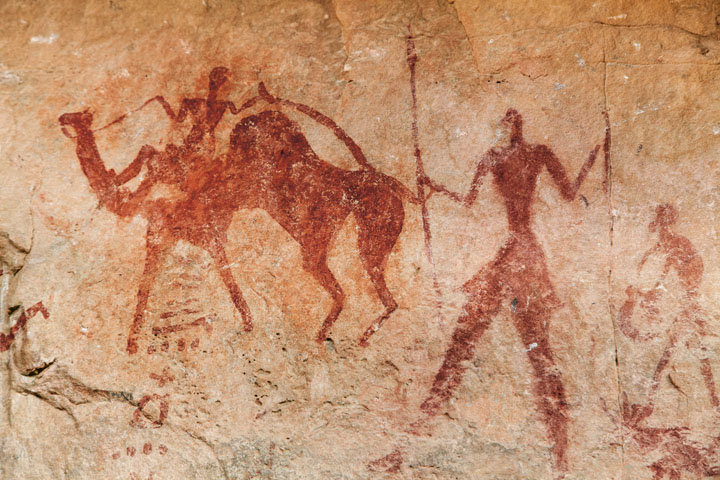

Clothing has long been a prime subject in art. This cave painting was found at Tassili nAjjer, in Algeria. The walking figure with two spears has some form of skirted garment at their hips. Some of the paintings at the site are thought to be around 10,000 years old.

For millennia, painting and sculpture have depicted humans, nature, the actions of humans, and their garments. Clothing and fabric have always been central to what artists wanted to express. Here is La Piet by Michelangelo, made for the Vatican in 14989, with its pointed symbolism of a mothering body that is extravagantly draped, the venerated male body mostly naked.

When you look at Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer, what do you actually see? Much of the canvas is dedicated not to the girl, or the earring, but to the fabric of her garments.