And in real life endings arent always neat, whether theyre happy endings, or whether theyre sad endings.

Stephen King

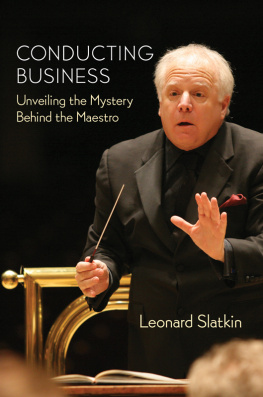

S o many subjects, only so many words. Every time I completed a chapter it seemed as if three or four other topics leapt into my mind. In fact, I wrote several sections that were more light-heartedfilled with anecdotes, stories, and tales. After a while, though, it became clear that they were not really appropriate for this book.

But they did get me started on another volume. While waiting for responses to the various chapter summaries, I began to compile information, particularly from my youth, that might make up a different kind of book than the others I have written. Early on, in my high school days, I thought that the short story might be an effective way for me to communicate. I started on a couple recently, and I have found that although they are quite different in writing style, I can still keep my own voice in this format. Time will tell whether or not I will complete this project.

In the meantime, I have also had a chance to reflect on what is contained in this publication. During the period between editing and printing, several of the subjects I have addressed in the book were already being discussed, but not because I had written anything. The musical world moves quickly when it comes to looking at issues it must confront. The problem is that only a few musical organizations actually take the big steps necessary to effect change.

We come into the discourse late. When the diversity issue is front and center, we spend way too much time talking about solutions rather than taking bold action. When we come up with potential remedies, they tend to be for the short term. Our health concerns have been discussed for years, and yet the same complaints that were in front of us fifty years ago persist. The list could go on and on.

Having relinquished my role as a music director, it is now possible for me to express my own feelings on these subjects a bit more freely than I could in the past. One of my uncles once told me that his goal in life was to get to the point that he could laugh at everyone. I am not quite that cynical. Rather, my desire is to say and write what I wish, and at the same time, I hope that some of my words spark an active response.

This might provoke some to wonder why I did not speak with the same candor earlier in my career. As a music director, one has to dance a little and play some games. These can be with the board, management, and orchestra. A music director is part politician, diplomat, parent, psychiatrist, cheerleader, and team player. Each organization is different, but the boundaries are the same. As often as I got in trouble for what I said, there were at least ten times as many occasions when I stayed quiet.

If and when we emerge from the pandemic, come to terms with meaningful diversity in all our sectors, and halt the society of divisiveness, perhaps levelheaded minds will prevail. Even though every orchestra is bound to its own community, there are commonalities that unite us. Healthy dialogue can lead to positive results if people are willing to put in the time and effort. We need to be finished thinking about how things were and focus on how they can be.

My love for music has been the driving force in my life. Finding ways to spread the word, in particular for so-called classical music and jazz, has been a passion. What you have read here was written in the hope that it spurs discussion, debate, and action. In any event, the music must continue to speak for all of us.

No statement should be believed because it is made by an authority.

Robert A. Heinlein

I n 1925, Richard Strauss wrote a short essay offering career advice for conductors:

TEN GOLDEN RULES

Written in the scrapbook of a young conductor

- Remember that you do not make music for your own amusement, but for the pleasure of your audience.

- Do not perspire when conducting; only the public ought to get warm.

- Conduct Salome and Elektra as if they were by Mendelssohn; fairy-music.

- Never look at the brass encouragingly; except with a quick glance for an important lead-in.

- On the contrary, never let the horns and woodwind out of your sight; if you hear them at all they are already too loud.

- If you think the brass is not strong enough, tone them down two points further.

- It is not enough yourself to hear every word of the singerwhich you know by heart anyway; the public also must be able to follow it without effort. If they dont understand what is happening they fall asleep.

- Always accompany the singer so as to enable him to sing without exertion.

- If you think you have reached the utmost Prestissimo, take the tempo as fast again.

- If you remember all this sympathetically, your rich talents and great knowledge will always be the unimpaired delight of your audience.

When we watch available videos of this great composer, we can infer that perhaps he is, of course, being facetious in some of his commandments. What we do not know is how he spent his time in rehearsal, which is where the work gets accomplished. As Strauss suggests, the performance is meant to please the listeners, and not to distract them with exaggerated mannerisms.

But that was a century ago, and times have changed. These days, I believe that we need a few more rules by which to be governed. There is no conductors legislative bureau, so we have to fend for ourselves. Nevertheless, unlike in Strausss time, we are held accountable to some stringent regulations imposed upon us by orchestras and unions. These must be obeyed, and as I will say often in this book, The clock is the enemy of the conductor.

With that in mind, as well as my own set of experiences at the podium, I offer these additional suggestions to add to the German maestros list:

- Do not talk too much. Orchestras only need to know six things: faster or slower, louder or softer, and shorter or longer. Thats all. Everything else is a variation on those themes. How can this be? Look at the next rule.

- Try to get an engagement with an orchestra that is in a country where you do not speak one word of the language. These days, there are always musicians who can communicate in English, no matter where in the world you are. Still, as a conductor, you are reduced, automatically, to keeping your remarks short and to the point. Your stick, eyes, and body do the work, not your mouth.

- When you arrive at the first rehearsal, look around and make sure that you know where everyone is situated in the orchestra. Few oversights are more embarrassing than giving a cue in one direction, only to have the sound come from another. Each orchestra has its own stage plot, and it is more than helpful to find out who is where.

- Check when the break occurs in the rehearsal and how long it lasts. This helps in planning what you will do during the rehearsal and gives you some idea about how to control the time you spend on each piece. More than one conductor has not been given this information and has run out of minutes before completing what he or she had planned.

- Make sure the music stand is at the correct height. Yes, this seems obvious, but you would be surprised by the number of conductors who just plunge right in, only to discover that they have to lean forward more than expected to turn the page. Ask a stagehand to help, or even a member of the orchestra.

- Learn where your dressing room is. When you come to the stage door, someone needs to take you to your quarters, but that will only occur on the first day. Sometimes the backstage area is like a labyrinth, involving multiple floors and staircases connected by long corridors. It is often equally difficult to get out of the building. That leads us to: