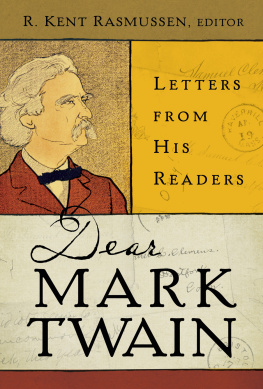

Dear Mark Twain

JUMPING FROGS

UNDISCOVERED, REDISCOVERED, AND CELEBRATED WRITINGS

OF MARK TWAIN

Named after one of Mark Twains best-known and beloved short stories, the Jumping Frogs series of books brings neglected treasures from Mark Twains pen to readers.

Is He Dead? A Comedy in Three Acts, by Mark Twain. Edited with foreword, afterword, and notes by Shelley Fisher Fishkin. Text established by the Mark Twain Project, The Bancroft Library. Illustrated by Barry Moser.

Mark Twains Helpful Hints for Good Living: A Handbook for the Damned Human Race, by Mark Twain. Edited by Lin Salamo, Victor Fischer, and Michael B. Frank of the Mark Twain Project, The Bancroft Library. Illustrated by Barry Moser.

Mark Twains Book of Animals, by Mark Twain. Edited with introduction and afterword by Shelley Fisher Fishkin.

Dear Mark Twain: Letters from His Readers. Edited with introduction and notes by R. Kent Rasmussen.

Dear Mark Twain

Letters from His Readers

Edited by

R. Kent Rasmussen

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BerkeleyLos AngelesLondon

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dear Mark Twain : letters from his readers / edited by R. Kent Rasmussen.

p. cm. (Jumping frogs ; 4)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26134-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780520955165

1. Twain, Mark, 18351910Correspondence. 2. Authors, American19th centuryCorrespondence. 3. Authors and readersUnited States. 4. Humorists, American19th centuryCorrespondence. I. Rasmussen, R. Kent. II. Twain, Mark, 18351910.

PS1331 . A 435 2013

818.409dc23

2012033968

Manufactured in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Rolland Enviro100, a 100% post-consumer fiber paper that is FSC certified, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with renewable biogas energy. It is acid-free and EcoLogo certified.

To the

memory of

Mary Keily,

faithful friend of

John Wilkes Booth

and John the Baptist

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of

the Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California

Press Foundation.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOREWORD

Reading this book gave me the fantods. The good fantods, if Huck will permit me such a distinction, not the bad ones. In fact it made me feel transported.

Transported back up the river of time, like some Connecticut Yankee, and deposited among a few of the ordinary Americans, along with a sprinkling of Europeans, who read the works of Mark Twain while he was still alive. Able to listen to them as they formed their thoughts about how his books affected them; their reckonings as to what sort of fellow he might be; their frequently nursed fantasies of him stepping from the ether and directly into their own lives. (And of hitting him up for a sawbuck or twoanother frequently nursed fantasy.)

R. Kent Rasmussen is not a time traveler, but he is the next best thing. In Dear Mark Twain he has achieved a triumph of warmhearted and bravura scholarship unique, as far as I can determine, in the plentiful annals of literary correspondence.

Granted, our library bookshelves are well stocked with collections of letters going back and forth between authors and those who knew them: family members, friends, enemies, editors, other eminences of their time. Mark Twain himself is well represented in this genre. Beginning with his first biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, editors have issued volumes of his epistolary conversations with his great friend William Dean Howells and with the financier Henry Huttleston Rogers, and of his tender courtship and married-love letters to Olivia Langdon. The splendidly annotated six-volume series Mark Twains Letters, edited by the Mark Twain Project at Berkeley, published by the University of California Press, and now available online, amounts virtually to a work of historical literature in itself. What we have not had before Mr. Rasmussens fine endeavor is an assemblage of letters to an author from common readers. Perhaps this is because few great writers have considered such messages to be worth keeping. Perhaps it is because their executors lacked the curiosity to riffle through any stacks of mail from obscure or anonymous sources. My own hunch is that the author of Life on the Mississippi and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn struck a chord among his fellow proletarian citizens that the prevailing priests of prose writingthe Emersons and Longfellows and Holmeses and Hawthornes, bless them allwere unable to reach. I will explore below the reasons why this is likely to be truth.

Whatever the reasons, Dear Mark Twain gives us an extremely rare, and thus exhilarating, glimpse into the sensibilities of nineteenth-century people. Of course one might point as well to documents such as letters from Civil War soldiers and the slave narratives gathered in the 1930s by WPA interviewers. Yet those chronicles, though often brilliant in style and sentiment, tend to be self-limiting: their concerns distill to their estranged families, their personal struggles, and their strategies for survival. The correspondence collected (and tirelessly annotated) here by Mr. Rasmussen is from everyday folks writing from the security of their everyday habitats, and thus more disposed to reveal themselves on a wide range of topics. They were people of both genders and all ages. They were farmers, schoolteachers and schoolchildren, businessmen, preachers, customs agents, inmates of mental institutions, con artists, dreamers of various sorts, and at least one former president.

Among the desires they held in common was one expressed in the oft-repeated postscript: Please write soon.

They could be cheekily artful (Gracious Sir:You are rich. To lose $10.00 would not make you miserable. I am poor. To gain $10.00 would not make me miserable. Please send me $10.00 [ten dollars]) and achingly artless (What I want to know is by what rule a fellow can infallibly judge when you are lying and when you are telling the truth. I write this in case you intend to afflict an innocent and unoffending public with any more such works). A fair amount were naive (Dear HuckI like your book and you and Tom Sawyer and Jim.... I wish you would write another book and tell us if Aunt Sally civilized you. How old are you? I am thirteen); a few were dyspeptic (Dear Sir: For Gods sake give a suffering public a rest on your labored wit.Shoot your trash & quit it.You are only an imitator of Artemas Ward & a sickening one at that & we are all sick of you, For Gods sake take a tumble & give U.S. a rest.).

Many of the lettersa good deal too many, for Mark Twains tastewere bids for his signature. (A few lines with your Name would be very acceptable ; I am taking a great deal of interest in your collection of long German words. I send you hereby [a] noble specimen, at the condition that you will send me your autograph, an autograph written by you not by your secretary). Clearly, the commodity value of this ancient fetish was rising in the Gilded Age. Even more infuriating to the author were the brazen assumptions that his literary talents were available to any stranger on demand:

Next page