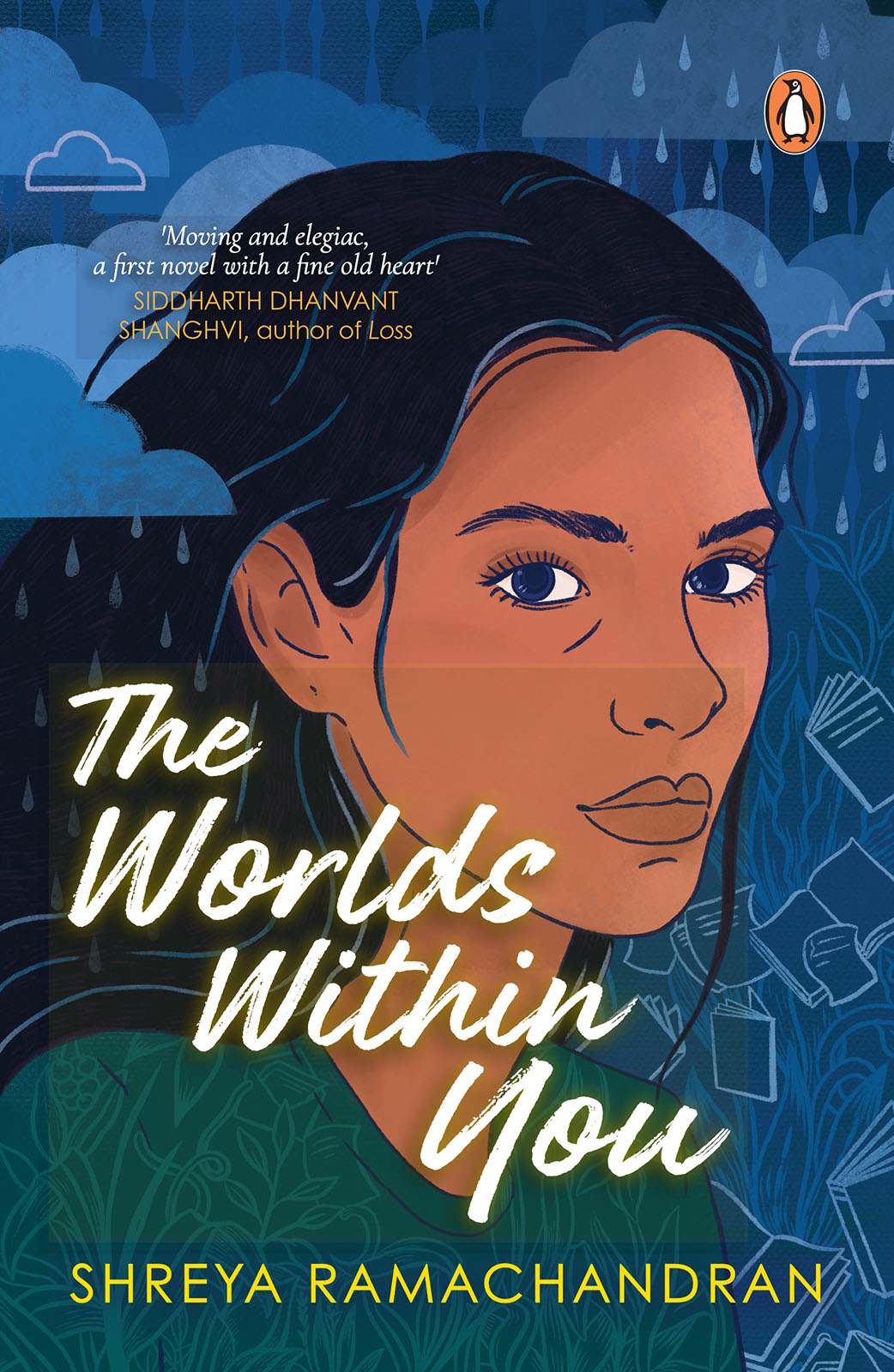

Shreya Ramachandran grew up in Chennai and studied South Asian literature and history. She writes about mental health on her blog, and her work has also appeared in The Hindu, the Swaddle and Spark magazine. She currently lives in Mumbai with an indie dog who behaves part cat. This is her first novel.

Advance praise for the book

Sensitive, observant, and honest, The Worlds Within You is a touching debut from a young writer to watchAnjali Joseph, author of Saraswati Park

Moving and elegiac, a first novel with a fine old heartSiddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi, author of Loss

A wonderfully written, clear-eyed novel about growing up, learning to live with yourself, your family and your memories. Moving, funny and incredibly realShabnam Minwalla, author of When Jiya Met Urmila

Tender and deceptively simple, The Worlds Within You is microscopically observed and at the same time has that quality of universality that sets apart good literature from merely passable literature. This may not be a unique novel in terms of plot or ideas, but a good writera title Shreya Ramachandran has earned with this bookcan make even the most quotidian subject matter interesting and affectingRoshan Ali, author of Ibs Endless Search for Satisfaction

At the moment I am finding it a little difficult, because it is all too new. I am a beginner in the circumstances of my own life

Rainer Maria Rilke

Prologue

Chennai, September 2006

Shouldnt it be breezy and rainy? It was warm, like the weather was on pause. Downstairs, everyone gathered for my grandfather Thathas funeral. They were talking about the show timings at the Mayajaal movie theatre; whether anyone remembered to call Roja, was she coming herself or did someone have to pick her up; did someone call the caterer for the tenth-day meal

Appa knocked at my door. I was lying on the bed, staring out at the trees. Appa appeared near my bed, wearing linen shorts and sandals. He looked like he was going to the beach, not to Thathas cremation.

Come, Appa said. He scrabbled over my blanket to find my hand and held it.

I dont want to, Appa. I hate seeing everyones faces.

Sam slunk out from behind Appa and came and sat on my bed. I agree, Sam said to Appa. She got in next to me and hugged me while lying entirely on top of me like a whale. Her gangly limbs stretched all across me. Her chin left little sharp indents in my shoulder.

Sam is arranging photo frames in the hall. Amma printed out a nice photo with the background blurred out and Thathas looking handsome in it. Come see.

No, Pa.

Sam, go downstairs quickly, Appa said. Ill come downstairs in one minute.

Appas hand was warm on mine. He got up to leave. I want you to write a poem about Thatha, okay? Can be anything you want, Appa said. Youre always scribbling in your notebook, no?

My notebook was a 2005 planner with the date and day in navy blue on every page, with a helpful Thought for the Day under it. Todays thought: He not busy being born is busy dyingBob Dylan. It was Thathas, and the first few pages had his writing, in Tamil I only half-understood.

Sakala Kalavali Maalai.

As he neared the door, Appa used the bottom of his shirt to clean my switchboard, wiping the top free of dust. You think Thatha would want you to just sit in your room like this?

I dont know. How would I know? Would I ever know?

Appa shut the door behind him, pausing before it closed.

In the evening, once everyone had left, Amma, Appa and Sam came into my room.

Amma took the diary from me and read out:

Everyone waits for it to rain.

Like the sun and the clouds are crying.

But it stays hot, the air like thick blankets made of wool.

Somethings changed. Is it something here?

Something you left before you went?

I sometimes wish...

Thats all? Appa asked.

Its fine, Ami, take some rest. Lets go, Shekar; give her some space, no? Amma said.

Sam and Amma slipped out of the room.

Finish it, baby, Appa said as he left.

*

1

A gap term, my father points out, is meant to be just a term.

We are sitting around the table at home in Adyar, Chennai. Its November 2013. Sam and Appa are eating idlis, their elbows all spread out amidst newspapers. Amma flits from the dining table to the kitchen. Appa is discussing my gap term and absence from college. It started as a week and is now over a month, threatening to spill into the new year because I dont know whether Ill go back in January.

Appa does not want such ambiguities. I look to Amma for help, but shes too busy talking to someone on her headphones. I hear a rumble, rather than individual words, of what she is saying.

I sometimes truly wish I could be Amma. I was born with basically no idea of what to say at any time. I spend all my time worrying about things that wont even happen. Is there a Norms of Comportment-type book that exists somewhere, and does everyone have it except me?

So, totally how many classes youve missed? Appa asks. He says this all enjambed, all one sentence.

One months worth, Sam speaks instead of me. As usual, I have an unfortunate habit of not speaking when I need to.

And they said you can go back in January, no? Ami? What did the dean say?

I think about what I will write in my journal later this evening about this conversation, in my room, which used to be Thathas room. Thatha had moved into the ground floor guest room, I moved into his old room upstairs, and Sam finally got her own room, which she said she needed so that she could unwind.

The dean told her she can just start in Jan and miss a term and graduate one term late, Appa, Sam says, solemnly smearing nei all over her plate and then laying her idli flat in it.

When did she say that? Appa asks.

I dont remember, I say.

You dont

Recently only, Pa. I think a week ago, Sam says.

Then write, tell her, Melanie

Marjorie, I correct.

Same thing. Say, Can I please confirm that I will start in Jan, is there any form I have to fill or any other formalities to be done, and say, hope you are well, kind regards, Appa says.

I dont say kind regards, I say.

I asked in school, Sam says, and they said Ami can teach. I asked Sharon Maam and everything.