Table of Contents

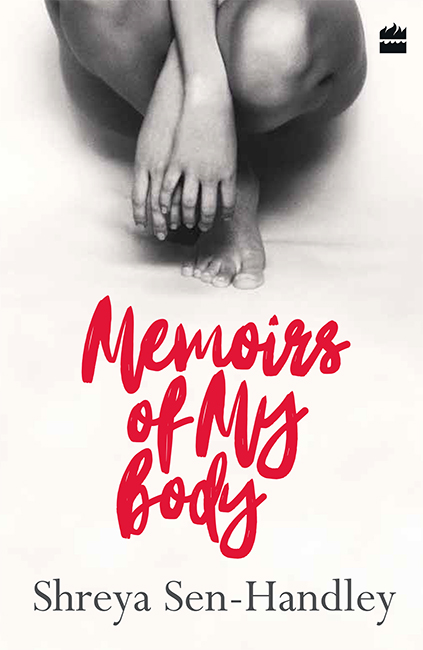

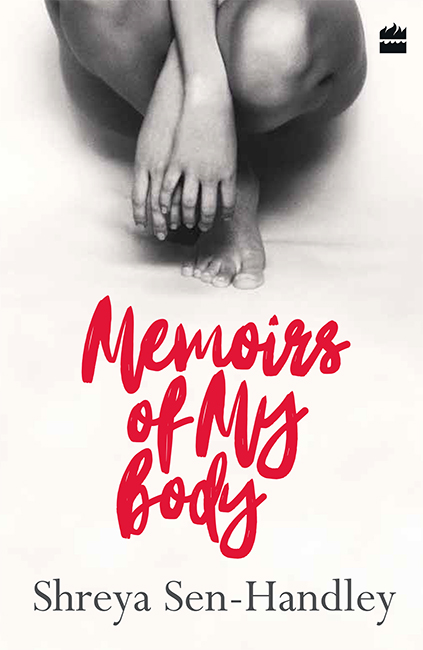

MEMOIRS OF

MY BODY

SHREYA SEN-HANDLEY

This ones for my rock and two shiny pebbles,

with all my love

Contents

Piglet looked around Hundred Acre Wood and thought, quite astutely, that it looked more like Sherwood Forest that fine summer morn. If fact and fiction are thrown together all higgledy-pig-gledy, what would you call it, Pooh?

I would call it fun, Piglet, said Pooh wisely, sounding not a bit like a Bear of Very Little Brain. Some may call it auto-fiction.

Piglet rolled this new term around in his head, trying to see if it worked for the thing hed written. Deciding he liked it very much indeed, he yanked the lid off their celebratory jar of honey, pushing it towards his friend for his bears share. Pooh dived in delightedly, even before he heard Piglet squeak enjoy.

But the wind had carried Piglets benediction to every other creature in the magically melding forest, and the fun was just about to begin.

In the hierarchy of summers of discovery, the first scorcher came early.

I had joined proper school that year and was in the middle of my first meanderingly long summer break, when I spotted the man who would usher in my coming of age. He walked into my world on a pair of weathered chappals and awakened the woman in me. Yes, in primary school. Dont jump the gun. Or reach for it. He didnt touch me. At least, not physically.

I called him Green Boy because I didnt know his name and was never likely to find out. Besides the age difference, there was also class between us. He was from the wrong side of the tracks. Literally. Beyond the little playing field opposite our home in Kolkata were perennially haze-enshrouded railway tracks that wound their way to nowhere.

Nowhere I knew, at any rate. Just turned six, I was on the brink of discovering the world. In the next few years, I would have traipsed all over South East Asia, absorbing everything it had to offer like a sponge. But first, there was another world to discover: my body. Discovered unexpectedly and inadvertently that long, hot, seventies summer of precocious reading. And Green Boy.

My parents were out working all day, my younger sister yet to arrive. So, I whiled away my time with a nanny who was kind but incapable of keeping my quick little brain occupied.

Are you reading again? she would ask me, concerned.

Yes, Id say for the umpteenth time, with growing irritation. I was fond of her but a little girl who could not be fobbed off with her practised bribes of keeleeps, bishkoot or sneaky half-hours of terrible television at the neighbours house (because Baba had refused to buy us a set), was beyond her capabilities. Where are the pictures? she would then ask suspiciously. She wasnt wrong to suspect something was afoot. It was a serious case of literary effrontery. I had outgrown picture books years ago, and on that dust-mote dappled afternoon, I was reading To Kill a Mockingbird.

And that was the least of it. That summer, I started reading books placed on shelves slightly above my head in the many bookcases in our house. These were the shelves for older kids. As the oldest child in the house (and the only one), I decided that meant me. As I ingested rows of previously inaccessible books, some lines stuck, and I would repeat them to myself with delight. Id rather take coffee than compliments just now, I would say la Jo March, while tottering through the hall in my moms high heels.

The radio was the other constant in my life, but neither Rabindra Sangeet nor filmi tunes did anything for me. Jim Morrison though, heard just once and in passing, left me with a feeling I couldnt fathom. My ayah, on the other hand, listened to Bollywoodsy warbling from the minute my mother left to teach in the morning to the moment she heard that first footfall outside our door in the late afternoon. Those first footsteps shattering the quiet of the afternoon could have belonged to anyone, including the cleaner who dropped in to shift the dust around twice a day. In the middle of the day, after she had served me a lunch of rice and fish, the ayah would retire to her small room for an hours kip, confident in the knowledge that I would happily spend the afternoon doing something quiet. Clearly, she was unaware that being quiet was often the worst thing an inquisitive child could be.

If I were to sleep, she would say as if she had any choice in the matter, what would you do? At first, I would answer her truthfully. I will play with my one-and-a-half dolls. (Baba didnt believe in buying those either) Then I moved on to the books, and mentioning them led to too many questions, even attempts at staying awake on her part. But when I discovered the delights of self-exploration, my answer went back to, I shall play. She would nod off, reassured. And I did play, didnt I?

But for that to happen, Green Boy had to saunter into my life.

Some muggy afternoons, after finishing with the books within reach and the measly music on offer, I had little else to do but swing on the railings of our first-floor balcony, watching the cricket on the little patch of green ahead. Boys from the neighbourhood ran, dived and shouted with glee as I observed them quietly.

Oi you monkey, the ball is racing to the boundary!

How do you expect me to see past your brother? Hes bigger than your house!

Then it would be fisticuffs before dusk, till the sweets shop owner walked over purposefully to clout one of the boys on the ear, which was the agreed signal for close of play.

I would watch all this, occasionally chortling to myself, turning my attention back to a book I was rereading (there was time to read and reread while Babloo, their slowest batsman, was at the crease) or cocking my head to hear the faint strains of music from the radio inside the house. If it was still on the same station, my ayah was asleep. One such afternoon, my eyes alighted on Green Boy and I grew up in nanoseconds.

He was a cricket-playing, little-else-doing young man. At six, even an imaginative six, I could not think of a fancier name than that. But then there was nothing fancy about Green Boy, and the sobriquet fitted him to a T. And it was a tee, his green, long-suffering tee that I named him after. You see, he never wore anything else. It was this, and a pair of khaki flares to go with it. As it was the late seventies, he had bristling sideburns to match. Maybe not green, but still flared and flora-like, taking over his narrow young face. He was in his teens: a distant god.

I watched him from my balcony as he played badly, oblivious to my scrutiny. Our paths only ever crossed at the sweets shop, which I was sent to regularly to stock up on my familys rosogolla (and related) requirements. Little did they know what danger they were exposing me to. No, not from the fellow himself but from the vistas opening up in my mind. Had they known the overcooked, overblown saga of love and rebellion that my head and heart were spawning, they would have thought twice about sending me to Lapur Lyangchas so often.

Occasional conversations between me and Green Boy went like this:

Dada-Boudi ki kinte pathieyecche?

Rosogolla.

Baah. Rosogollar moton mishti aar hoyena.

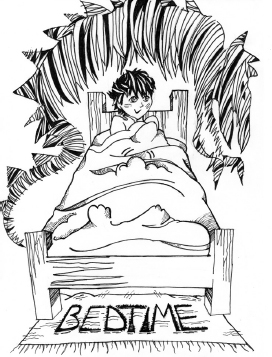

And I would blush a deep red and scurry home with a bhnar of rosogolla, convinced hed indirectly admitted to a soft spot for my sweet nature. He soon entered my dreams by day and by night. The former were innocuous enough to start with. It was in the latter that he started doing strange things to me I couldnt name. I would toss and turn through the night and find wet streaks in my underpants in the morning. I worried initially that I had gone back to bed-wetting, but then I had a waking dream about him. A daydream, where he did indescribable, but not unlikeable, things to me. And suddenly, I had a whole new set of worries. Including those wet streaks which were now revealed to be not-wee. But also, wonderfully, secret delights to indulge in.