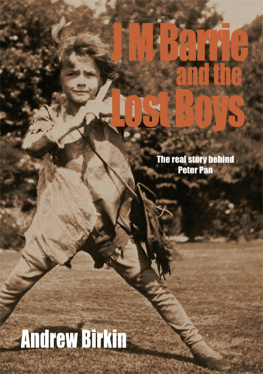

AN EDINBURGH ELEVEN

PENCIL PORTRAITS FROM COLLEGE LIFE

* * *

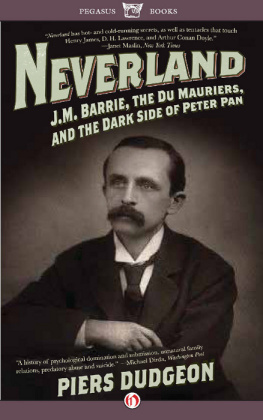

J. M. BARRIE

*

An Edinburgh Eleven

Pencil Portraits from College Life

First published in 1889

ISBN 978-1-62013-946-2

Duke Classics

2014 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Contents

*

I - Lord Rosebery

*

The first time I ever saw Lord Rosebery was in Edinburgh when I was astudent, and I flung a clod of earth at him. He was a peer; those weremy politics.

I missed him, and I have heard a good many journalists say since thenthat he is a difficult man to hit. One who began by liking him and isnow scornful, which is just the reverse process from mine, told me thereason why. He had some brochures to write on the Liberal leaders, andgot on nicely till he reached Lord Rosebery, where he stuck. In vain hewalked round his lordship, looking for an opening. The man wasnaturally indignant; he is the father of a family.

Lord Rosebery is forty-one years of age, and has missed manyopportunities of becoming the bosom friend of Lord Randolph Churchill.They were at Eton together and at Oxford, and have met since. As a boy,the Liberal played at horses, and the Tory at running off with otherboys' caps. Lord Randolph was the more distinguished at the university.One day a proctor ran him down in the streets smoking in his cap andgown. The undergraduate remarked on the changeability of the weather,but the proctor, gasping at such bravado, demanded his name andcollege. Lord Randolph failed to turn up next day at St. Edmund Hall tobe lectured, but strolled to the proctor's house about dinner-time."Does a fellow, name of Moore, live here?" he asked. The footmancontrived not to faint. "He do," he replied, severely; "but he are atdinner." "Ah! take him in my card," said the unabashed caller. TheMerton books tell that for this the noble lord was fined ten pounds.

There was a time when Lord Rosebery would have reformed the House ofLords to a site nearer Newmarket. As politics took a firmer grip ofhim, it was Newmarket that seemed a long way off. One day at Edinburghhe realized the disadvantage of owning swift horses. His brougham hadmet him at Waverley Station to take him to Dalmeny. Lord Roseberyopened the door of the carriage to put in some papers, and then turnedaway. The coachman, too well bred to look round, heard the door shut,and, thinking that his master was inside, set off at once. Pursuit wasattempted, but what was there in Edinburgh streets to make up on thosehorses? The coachman drove seven miles, until he reached a point in theDalmeny parks where it was his lordship's custom to alight and open agate. Here the brougham stood for some minutes, awaiting LordRosebery's convenience. At last the coachman became uneasy anddismounted. His brain reeled when he saw an empty brougham. He couldhave sworn to seeing his lordship enter. There were his papers. Whathad happened? With a quaking hand the horses were turned, and, drivingback, the coachman looked fearfully along the sides of the road. He metLord Rosebery travelling in great good humor by the luggage omnibus.

Whatever is to be Lord Rosebery's future, he has reached that stage ina statesman's career when his opponents cease to question his capacity.His speeches showed him long ago a man of brilliant parts. His tenureof the Foreign Office proved him heavy metal. Were the Gladstonians toreturn to power, the other Cabinet posts might go anywhere, but theForeign Secretary is arranged for. Where his predecessors had cloudedtheir meaning in words till it was as wrapped up as a Mussulman's head,Lord Rosebery's were the straightforward despatches of a man with hismind made up. German influence was spoken of; Count Herbert Bismarckhad been seen shooting Lord Rosebery's partridges. This was theevidence: there has never been any other, except that German methodscommended themselves to the minister rather than those of France. Hisrelations with the French government were cordial. "The talk ofBismarck's shadow behind Rosebery," a great French politician saidlately, "I put aside with a smile; but how about the Jews?" Probablyfew persons realize what a power the Jews are in Europe, and in LordRosebery's position he is a strong man if he holds his own with them.Any fears on that ground have, I should say, been laid by his record atthe Foreign Office.

Lord Rosebery had once a conversation with Prince Bismarck, to which,owing to some oversight, the Paris correspondent of the Times was notinvited. M. Blowitz only smiled good-naturedly, and of course hisreport of the proceedings appeared all the same. Some time afterwardLord Rosebery was introduced to this remarkable man, who, as is wellknown, carries Cabinet appointments in his pocket, and complimented himon his report. "Ah, it was all right, was it?" asked Blowitz, beaming.Lord Rosebery explained that any fault it had was that it was allwrong. "Then if Bismarck did not say that to you," said Blowitz,regally, "I know he intended to say it."

The "Uncrowned King of Scotland" is a title that has been made for LordRosebery, whose country has had faith in him from the beginning. Mr.Gladstone is the only other man who can make so many Scotsmen takepolitics as if it were the Highland Fling. Once when Lord Rosebery wasfiring an Edinburgh audience to the delirium point, an old man in thehall shouted out, "I dinna hear a word he says, but it's grand, it'sgrand!" During the first Midlothian campaign Mr. Gladstone and LordRosebery were the father and son of the Scottish people. Lord Roseberyrode into fame on the top of that wave, and he has kept his place inthe hearts of the people, and in oleographs on their walls, ever since.In all Scottish matters he has the enthusiasm of a Burns dinner, andhis humor enables him to pay compliments. When he says agreeable thingsto Scotsmen about their country, there is a twinkle in his eye and intheirs to which English scribes cannot give a meaning. He has unveiledso many Burns statues that an American lecturess explains: "Curiousthing, but I feel somehow I am connected with Lord Rosebery. I go to aplace and deliver a lecture on Burns; they collect subscriptions for astatue, and he unveils it." Such is the delight of the Scottishstudents in Lord Rosebery that he may be said to have made thetriumphal tour of the northern universities as their lord-rector; helost the post in Glasgow lately through a quibble, but had the honorwith the votes. His address to the Edinburgh undergraduates on"Patriotism" was the best thing he ever did outside politics, and madethe students his for life. Some of them had smuggled into the hall achair with "Gaelic chair" placarded on it, and the lord-rectorunwittingly played into their hands. In a noble peroration he exhortedhis hearers to high aims in life. "Raise your country," he exclaimed[cheers]; "raise yourselves [renewed cheering]; raise your university[thunders of applause]." From the back of the hall came a solemn voice,"Raise the chair!" Up went the Gaelic chair.

Even Lord Rosebery's views on imperial federation can become acompliment to Scotland. Having been all over the world himself, andfelt how he grew on his travels, Lord Rosebery maintains that everyBritish statesman should visit India and the colonies. He said thatfirst at a semi-public dinner in the countryand here I may mentionthat on such occasions he has begun his speeches less frequently thanany other prominent politician with a statement that others could begot to discharge the duty better; in other words, he has several timesomitted this introduction. On his return to London he was told that hiscolleagues in the Administration had been seeing how his scheme wouldwork out. "We found that if your rule were enforced, the Cabinet wouldconsist of yourself and Childers." "This would be an ideal cabinet,"Lord Rosebery subsequently remarked in Edinburgh, "for it would beentirely Scottish," Mr. Childers being member for a Scottishconstituency.