Contents

Guide

Originally published as lami qui ne ma pas sauv la vie by ditions Gallimard.

ditions GALLIMARD, 1990

This edition Semiotext(e) 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Semiotext(e)

PO BOX 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031

www.semiotexte.com

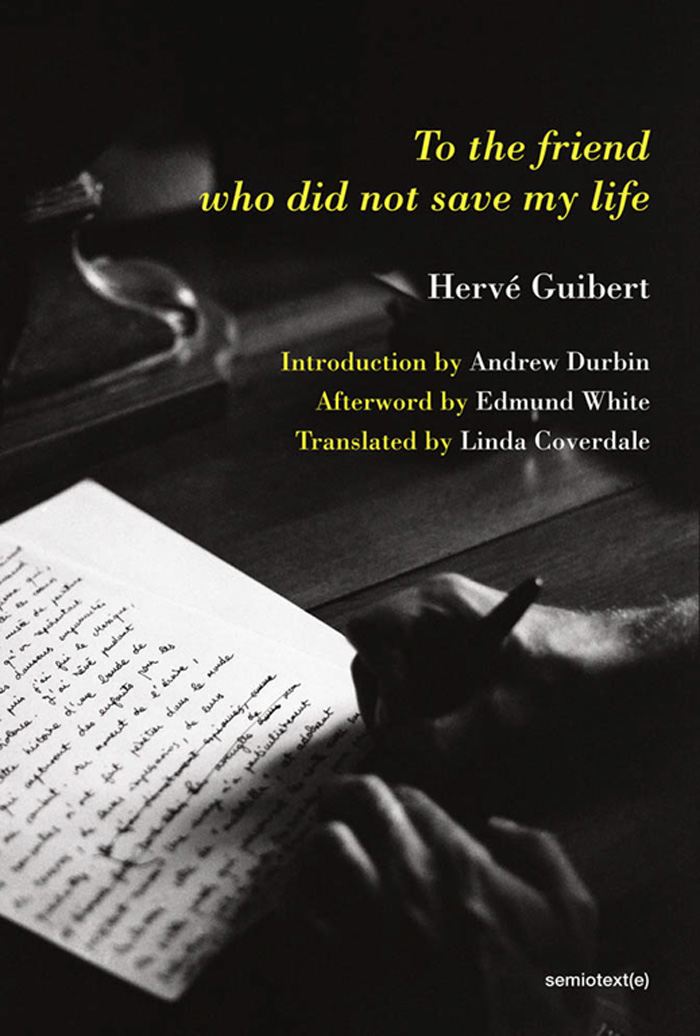

Cover Photograph: Hans Georg Berger, First page of the script of Vous mavez fait former des fantmes, Elba 1986.

Design: Hedi El Kholti

ISBN: 978-1-63590-123-8

Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England

d_r0

Introduction by Andrew Durbin

A Guide for Living

In 1988, the French novelist and photographer Herv Guibert was diagnosed with HIV. Two years later, ditions Gallimard published To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990), a stark, autobiographical book about his desperate effort to gain access to an experimental AIDS vaccine. To the Friend made Guibert both wealthy and famous, especially after an appearance on the French culture program Apostrophes. Posters of his handsome face went up around Paris, transforming him into a symbol of the intense suffering of seropositive men and women at the time. The cost of living is captured in solemn eyes and pursed lips and long spindly sentences. Though he promises in the opening section of To the Friend to become one of the first people on earth to survive this deadly malady, he would die the following year, on December 27, 1991, only a few days after his 36th birthday, having written an additional five extraordinary books, most of which would be published posthumously.

To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life is composed of a series of portraits of friends and lovers whom illness and its specters torment throughout its hundred chapters. Marinebased on the actor Isabelle Adjaniis dogged by rumors that she is HIV-positive after a mid-career debacle on the Paris stage. The cocky, Miami-based pharmaceuticals executive and the novel's titular friend, Bill, brags about his connections to Melvil Mockney (a stand-in for the inventor of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk), who had hoped to introduce immune therapy to combat HIV/AIDS; both the connection and Mockney's therapy come to nothing. (As Mathieu Lindon recalls in his memoir Learning What Love Means (2011), To the Friend 's manuscript title was Pends-toi Bill! or, Go Fuck Yourself, Bill!) Jules and his wife Berthea couple based on Guibert's long-time lover Thierry Journo and his wife Christine Seemullerfear not only for themselves, but their children when Jules discovers that he, too, is seropositive. Other sickened men flit by in the novel's short chapters: sons, boyfriends, brothers, strangers. The central and most arresting portrait is of Guibert's mentor, the philosopher Muzil, based on Michel Foucault, whose death the writer repeatedly returns to in the first half of the novel.

Guibert's gripping revelation of Foucault's final days in the character of Muzil, which had been kept secret by the privacy-obsessed French press, caused a stir in the country, rocketing Guibert to fame late in his young life. Muzil is cavalier about the virus when the first reports of a gay cancer arrive in Europe, and later he even admires its revolutionary effect on the community. After an annual trip to San Francisco, where Muzil prowls the city's famous bathhouses, he remarks that AIDS had created new complicities, new tenderness, new solidarities in the city's cruising grounds. When he tests positive, he conceals his diagnosis from almost everyone, even his partner. Death, Muzil argues, should retain an element of profound mystery, for the living and the dying. In a passing conversation with Guibert, the philosopher provocatively imagines a death resort built around such obscurity, where unwell or aging people who are ready to die slip behind a painting, into a secret room, after which they are never heard from againan inversion of Dorian Gray's famous portrait, with the illusion of beauty swapped for good health. Muzil's resort provides a concise image for Guibert's late fiction, which is full of disappearances, revisions, and redundancies as characters die and resurrect, sometimes turn to shambles only to be found, a few pages later, back on their feet. In To the Friend, Guibert offers one brutal glimpse behind Muzil's resort painting after another. At the height of his intellectual powers, the philosopher struggles, in his final year, to complete a series of books on human sexuality but, like Foucault, fails to do so. (His name is likely a nod to the Austrian writer Robert Musil, who left his epic novel The Man Without Qualities (193043) unfinished. The substitution of an s for the last letter of the alphabet provides a note of finality both men were otherwise denied.) Eventually, he loses his memory, his ability to write, and his physical capacities; finally, he collapses in a pool of blood in his Parisian apartment.

I can imagine several endings, Guibert writes toward the beginning of To the Friend, all of which fall for the moment under the heading of premonition or heartfelt desire, but the whole truth is still hidden from me, and I tell myself that this book's raison dtre lies along this borderline of uncertainty, so familiar to sick people everywhere. Several endings meant that Guibert would devote much of his later work to the unfinished storiesand livesshaped by this recursive sickness which, like the novel itself, is embedded with the history of venereal disease and its treatment, as well as the new complicities, new tenderness, new solidarities that attend to terminal illness.

After Guibert tests positive in the second half of the novel, his various, multiplying infections are remedied at the Institut Alfred-Fournier, which had served as an important syphilis hospital in the 19th century. Here Guibert points to another quiet substitution, one within the broader medical project that has long sought to pathologize gay life: that of HIV/AIDS for syphilis within epidemiological healthcare in France in the 1980s, from the way it treated gay men to the very hospitals it used to care for them. With the rise of HIV/AIDS, the old Institut was quite instantly revitalized, enriched by the blood of seropositive patients, Guibert observes. He describes the nurses as if they might be wearing that season's Yves Saint Laurent: With semisheer stockings and flats, straight skirts, and tasteful necklaces worn over their white smocks, the nurses look very chic They slip on their latex gloves as though they were velvet gloves for a gala evening at the opera. But the hospital's revival doesn't change the way doctors approach the treatment of HIV/AIDS; they are anxious about their patients, just as the patients are anxious about themselves. Physical, emotional, and intellectual contact between them (not only at the hospital, but in the pharmaceutical labs of the major manufacturers) is kept at a minimum, a major issue which would be taken up in the United States by ACT-UP. Governments meanwhile were debating whether to brand seropositive people in Europe, Guibert reports, or forcibly test at-risk groups on intra-continental borders.

This follows, of course, a long history of blaming gay men for the prevalence of venereal disease, and for dismissing them as hopeless cases for modern medicine, people who could never be saved. Guibert's near contemporary, the philosopher and activist Guy Hocquenghemwho died from AIDS-related complications in 1988describes the treatment of syphilis in