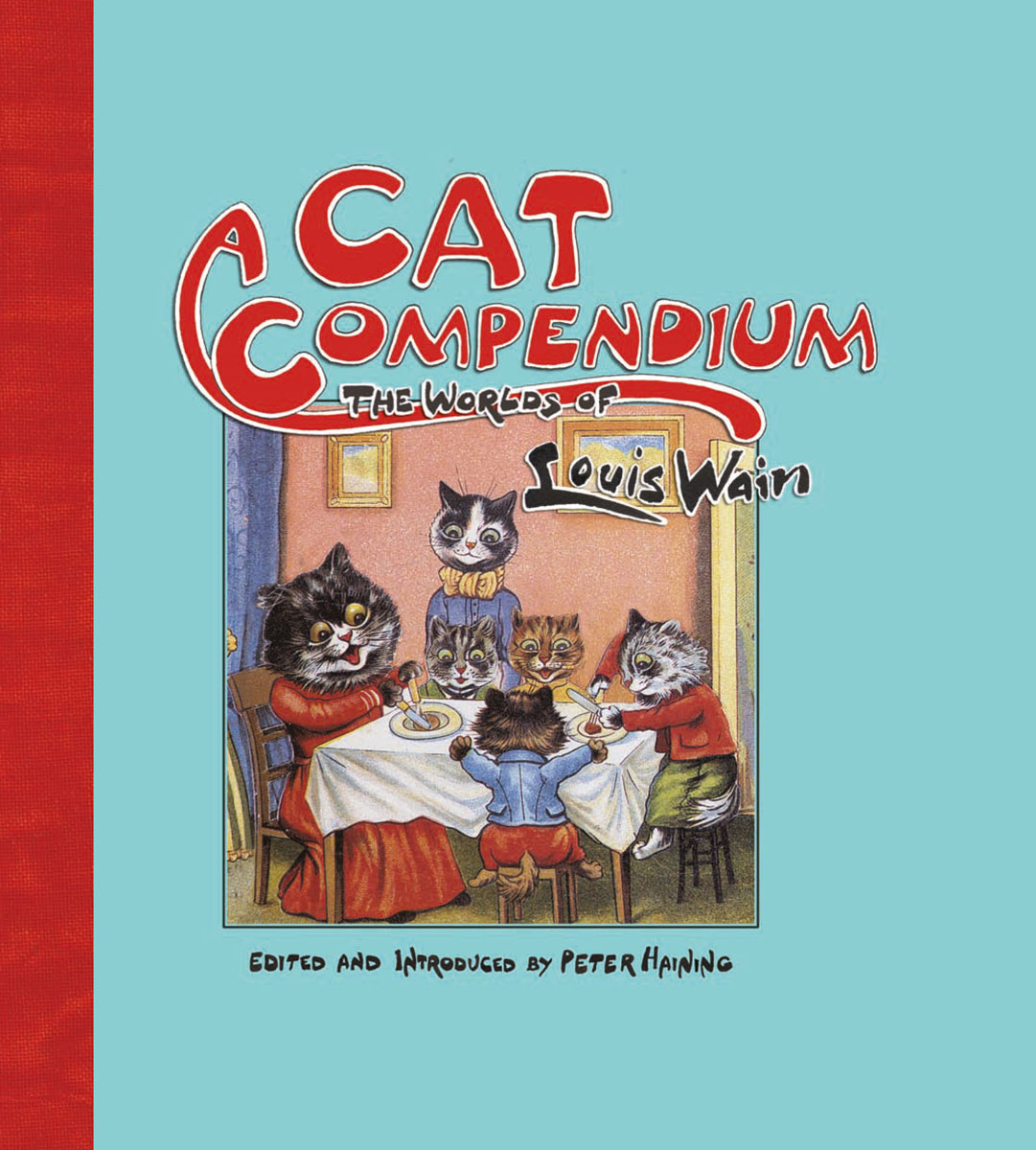

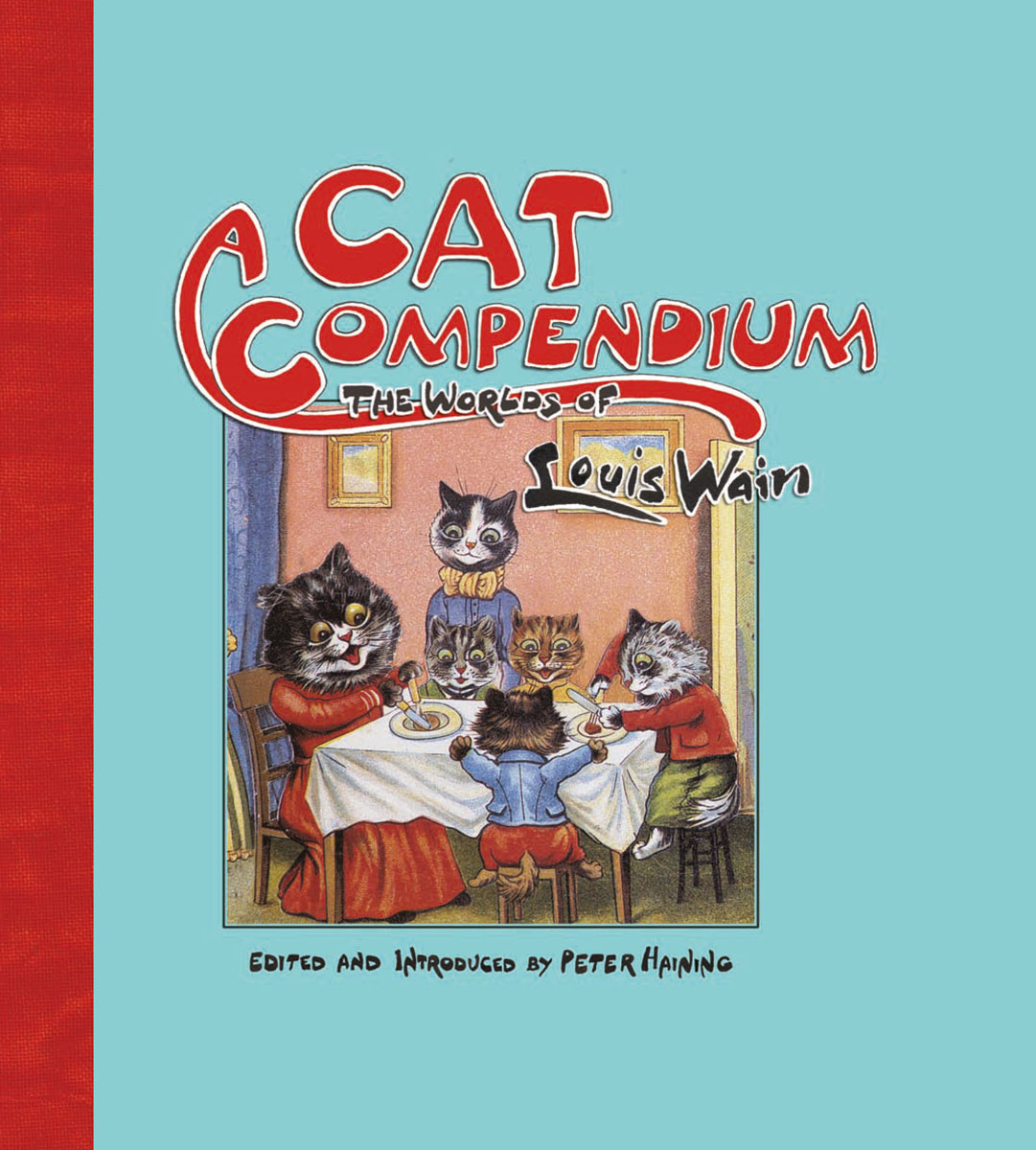

A CAT COMPENDIUM

The Worlds of Louis Wain

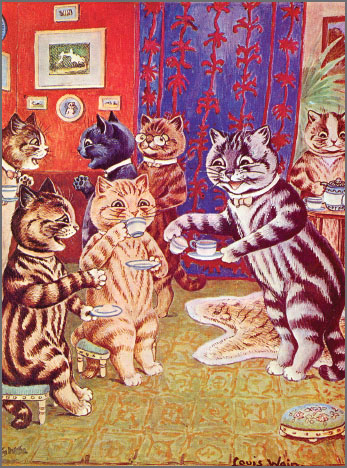

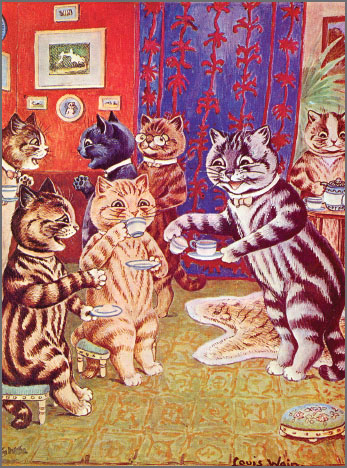

Louis Wains witty feline illustrations sold many hundreds of thousands of copies around the world, earning their creator the title the Hogarth of cat life, and A Cat Compendium brings together the very best of his work. With a biographical introduction by editor Peter Haining, a selection of the artists writings and more than sixty of Wains pictures, it is an ideal introduction to the fascinating and sometimes bizarre worlds of Louis Wain.

I N M EMORY OF C HIPPY, S PEC, T ICKLES, K EVIN AND S LUGGY AND FOR E DWARD, OCCASIONALLY K NOWN AS P RINCE

Louis Wain has made the cat his own. He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world.

H.G. Wells, August 1925

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the discovery in an attic of a collection of cuttings and illustrations by and about Louis Wain that had been assembled over half a century ago by one of my relatives. The lady had been a life-long cat lover and an admirer of Wains pictures, which she had clipped from newspapers and magazines and even a few books and carefully mounted in a scrapbook. It is from the pages of this scrapbook that the articles and pictures by Wain have been selected to give as wide-ranging an indication of the man and his talent as possible.

The task has been one that I have enjoyed immensely, and I am delighted that it has been possible to include a selection of very striking and often most unusual full-colour illustrations that Wain created especially for the various magazines and books to which he contributed. The captions to a number of the pictures were those that the owner of the scrapbook had written beneath them, so if any sharp-eyed expert has reason to believe the words may be different from those that Wain originally wrote, I apologize now. The pictures, of course, speak for themselves and hardly require any words!

I should also like to thank the following for their assistance in making this book possible: my friends Chris Scott, Nita Rigden, Denis Gifford, Chris Beetles and the late Bill Lofts, who tracked down the copy of Wains extremely rare article How I Draw My Cats. I am also grateful to the staff of the British Newspaper Library at Colindale for checking a number of publications and dates for me; also the publishers Thames and Hudson for permission to quote from Louis Wains Cats by Michael Parkin, and Michael OMara Books Ltd for the extract from Louis Wain: The Man Who Drew Cats by Rodney Dale. All other sources are acknowledged in the text.

Peter Haining

Boxford, Suffolk

C ONTENTS

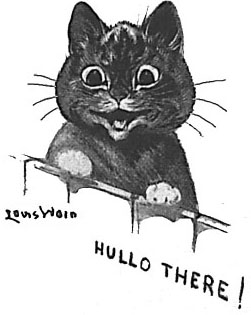

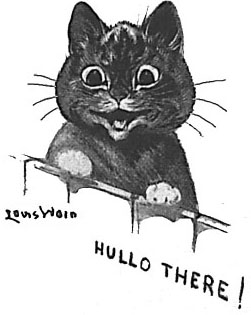

T HE ARCHETYPAL L OUIS W AIN C AT (T HE I DLER, J ANUARY 1896)

T HE W ORLDS OF L OUIS W AIN

In the spring of 1929, Bethlehem Royal Hospital in St Georges Field, Lambeth, was a mental institution regarded with a mixture of pity and fear by many Londoners. The tall, somewhat forbidding building was, in fact, still referred to by some locals as Bedlam, and local gossip would occasionally refer to the hospitals past when curiosity-seekers went there to stare and make fun of the extraordinary antics of the lunatics locked in their cells.

By the 1920s, however, the Bethlehem was acknowledged as the worlds oldest psychiatric hospital, and its history had been traced back as far as the thirteenth century. Originally located in Bishopsgate, where it had been a priory for the men and women of the Order of the Star of Bethlehem, it had, by the following century, become a hospital and in 1377 began treating distracted patients.

It was during the reign of Henry VIII that the institution became notorious for the inhumane and brutal way in which the inmates were treated and became known as Bedlam. In 1675, the hospital was moved to new premises in Moorfields, and soon after that the freak shows began. These appallingly insensitive open days allowed the citizens of London, for the price of a penny, to enter the buildings and amuse themselves at the expenses of the hapless inmates.

The hospital was immortalized in the public imagination in 1735 by the artist William Hogarth in a scene from A Rakes Progress, in which the terrible fate of a merchants son whose debauched lifestyle had brought about his incarceration is depicted reflecting contemporary medical opinion that madness was caused by moral weakness. Thankfully, a change in attitudes was soon forthcoming, inmates now being referred to as patients and separate wards set up for the curables and incurables.

The scars of the past could not be entirely erased, however. The word bedlam was already in common usage for all lunatic asylums, as well as any place or scene of wild turmoil and confusion. The name Tom OBedlam had similarly been coined to describe anyone who was discharged from the hospital and provided with a small tin plate so that he could legally beg on the streets of London.

The nineteenth century saw the Bethlehem Royal Hospital move a third time, to Lambeth, where it would remain until 1930, before becoming what is now the home of the Imperial War Museum. These new premises proved a far cry from the horrors of the old Bedlam although some of the misconceptions about the place still persisted individual rooms being provided for patients along a series of galleries.

In 1929, Room 7 on Gallery 2 was occupied by a quietly spoken man in old-fashioned clothes who gave the impression to staff and visitors alike of being more of an eccentric than a madman. Certainly his room was piled high with paper, books, newspapers, magazines and a host of other smaller items indicating that he was a hoarder, while his constant preoccupation with writing and drawing set him aside from most of the other patients.

Matters came to a head that spring when the authorities finally insisted that Room 7 had to be cleaned. The patient stood silently by, watching without any obvious sign of annoyance as two staff members began to shift the piles of junk. He made no move either when some mice ran out from behind the yellowing newspapers, sending the female cleaner shrieking into the corridor.

At this, the man began to search around in the jumble, evidently looking for something. When he found a piece of paper, he sat down on the bed and began to draw. Whether the picture was intended to be a joke, the subject was immediately recognizable to the cleaners as they again got on with their work.

The pencil sketch was of a grinning cat with saucer-shaped eyes and a rather distorted body and legs. Clearly the man who had drawn it was no ordinary patient; indeed, he had once been the most famous cat artist on earth and the creator of a unique world known as Catland. His name was Louis Wain.

Next page