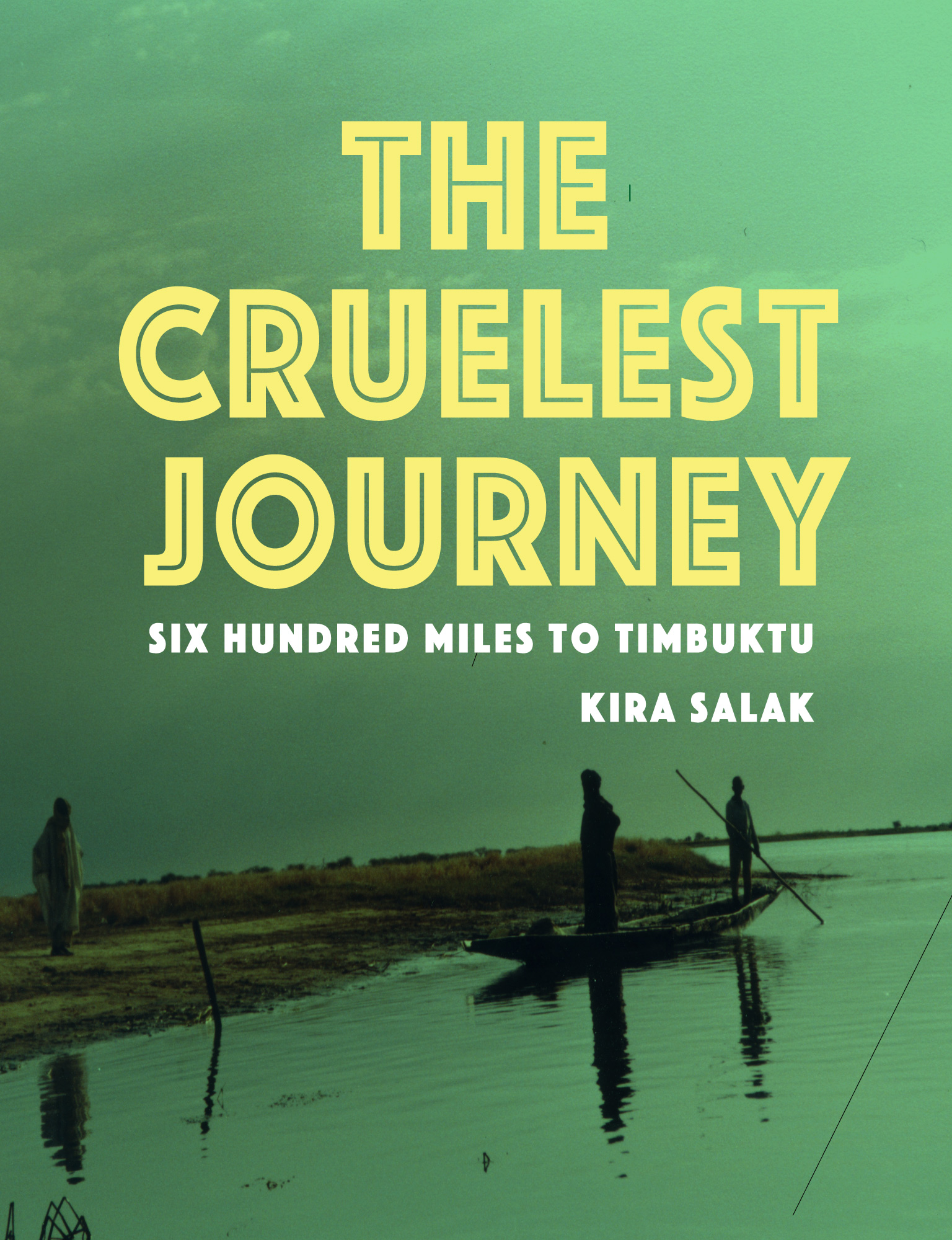

Kira Salak - The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu

Here you can read online Kira Salak - The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Restless Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu

- Author:

- Publisher:Restless Books

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

DESCRIPTION

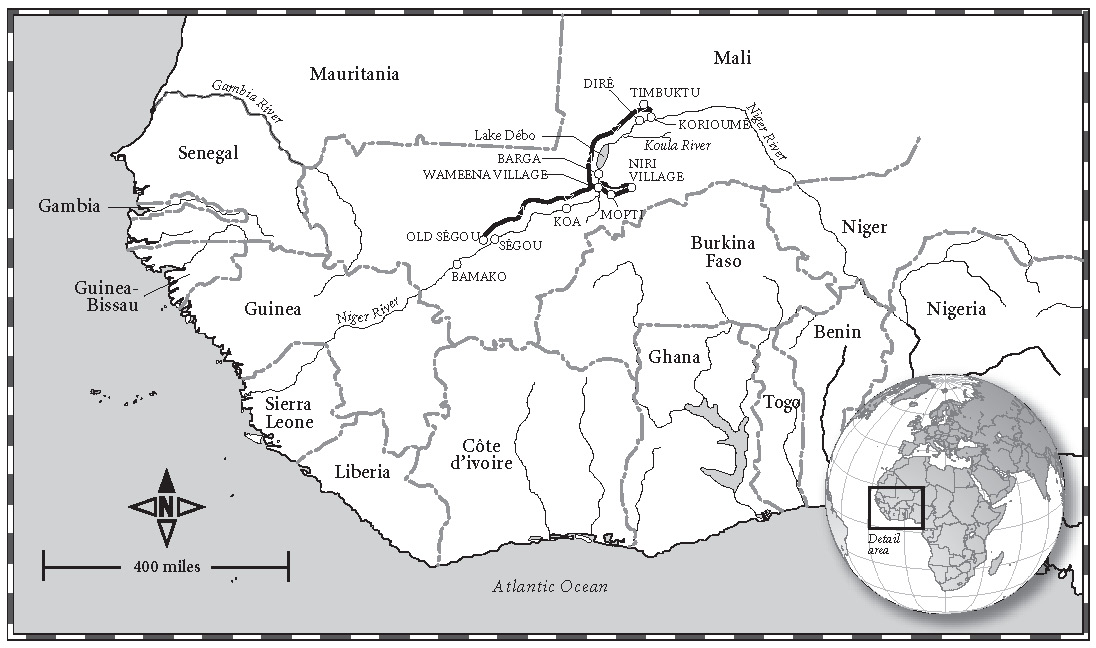

Kira Salak became the first person in the world to kayak alone 600 miles on the Niger River of Mali to Timbuktu, retracing the fatal journey of the great Scottish explorer Mungo Park. Enduring tropical storms, hippos, rapids, the unrelenting heat of the Sahara desert, and the mercurial moods of this notorious river, Kira Salak traveled solo through one of the most desolate and dangerous regions in Africa, where little had changed since Mungo Park was taken captive by Moors in 1797.

Dependent on locals for food and shelter each night, Salak stayed in remote mud-hut villages on the banks of the Niger, meeting Dogan sorceresses and tribes who alternately revered and reviled herso remarkable was the sight of an unaccompanied white woman paddling all the way to Timbuktu. Indeed, on one harrowing stretch she barely escaped with her life from men chasing after her in canoes. Finally, weak with dysentery but triumphant, she arrived in the fabled city of Timbuktu and fulfilled her ultimate goal: buying the freedom of two Bella slave women. This unputdownable story is also a meditation on courage and self-mastery by a young adventuress without equal, whose writing is as thrilling as her life.

REVIEWS

A deeply personal travel memoir, Salak is not merely a traveller, she is an explorer, and her voyage is an expedition of self-discovery. She sets off in ominously stormy weather 206 years to the day after Park did, and shares in cutting detail the encounters of the Niger like a mercurial god, meting out punishment and benediction on a whim. Salak seduces us with an honest audacious story of the splendour and austerity of a journey through a far-off land.

Kirkus Reviews UK

Salaks second travel memoir takes her down the Niger River to Timbuktu, following the trail of Scottish explorer Mungo Park, who more than 200 years before he attempted the same journey. Salak decides to take the journey alone on a kayak, hoping to recapture Parks sense of wonder and determination. Salaks trip is deeply personal, and she shares her fears, her triumphs, and her thoughts along the way with the reader, making it an accessible, involving journey for her audience.

Booklist

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kira Salak won the PEN Award for journalism for her reporting on the war in Congo, and she has appeared five times in Best American Travel Writing. A National Geographic Emerging Explorer and contributing editor for National Geographic Adventure magazine, she was the first woman to traverse Papua New Guinea and the first person to kayak solo 600 miles to Timbuktu. She is the author of three booksthe critically acclaimed work of fiction, The White Mary (published by Henry Holt), and two works of nonfiction: Four Corners: A Journey into the Heart of Papua New Guinea (a New York Times Notable Travel Book) and The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu. She has a Ph.D. in English, her fiction appearing in Best New American Voices and other anthologies. Her nonfiction has been published in National Geographic, National Geographic Adventure, Washington Post, New York Times Magazine, Travel & Leisure, The Week, Best Womens Travel Writing, The Guardian, and elsewhere. Salak has appeared on TV programs like CBS Evening News, ABCs Good Morning America, and CBCs The Hour. She lives with her husband and daughter in Germany. Learn more at her website, www.kirasalak.com.

Kira Salak: author's other books

Who wrote The Cruelest Journey: Six Hundred Miles to Timbuktu? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.