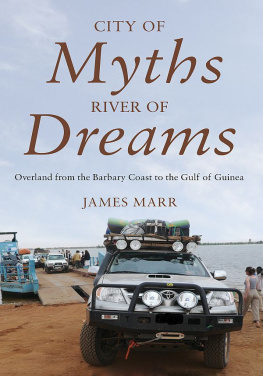

Having laboured as a garage mechanic, farmer, hotelier, property developer, ship manager, scribbler and overlander, James Marr reckons to be a jack of many trades, though a master of none.

Along with his wife, and an abundance of unwelcome wildlife, he currently lives in the back of his car, somewhere along the Pan-American Highway.

You can visit James blog at http://cityofmythsriverofdreams.com

Also by James Marr

WHY DO GOATS CLIMB TREES?

Copyright 2013 James Marr

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 9781783067923

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

ALL GREAT JOURNEYS BEGIN

WITH A HANGOVER

BORNHOLM April 2008

A Baltic storm lashed the island. Inside the restaurant four bodies huddled round a table. Rain splattered the windows; thunder split the night sky. A thin bottle containing a fiery liquid made the rounds. We were determined in our quest; an adventure was in the offing. Glasses of schnapps clashed together.

To Timbuktu! we declared

Timbuktu has long held a curious allure. From the late eighteenth century, this mythical city provoked a succession of outwardly sane men to abandon their families and the relative comforts of Europe, to board a sailing boat armed with a musket, a compass and a loud frock-coat, to step ashore on the disease-ridden shores of West Africa and, in the company of an interpreter and a couple of asses, vanish into a menacing land. They were called explorers, or adventurers, or geographical missionaries, and they were feted as heroes, dead or alive. When the illusive Saharan city was eventually discovered, they found the gates hanging off their hinges, sand piling up in the alleyways, the buildings crumbling to dust, and the promised gold long gone. That was the cruel irony of their quest. And yet it bore legends.

Thankfully, our travels through West Africa were not burdened by the responsibilities weighing those explorers of old. We were not searching for the route of a mighty river, or trying to locate a lost City of Gold. Neither were we to fill in the blank spaces on maps that were the imaginings of ancient and medieval geographers. And in these days of internet, accessible travel and mobile telephones, the very idea of discovering and recording little known kingdoms is laughable. In truth, the overland journey we were embarking on, with our modern Toyota Hilux 4X4, was a breeze, especially after wed loaded the false floor with an RPG 7 grenade launcher, a few Uzi sub-machine-guns, a pair of Desert Eagle .44 magnums and Oh, okaymaybe not.

Nevertheless, what might we be up against on the road to Timbuktu? African law and order itself can be considered the definitive portrayal of the hold-up, and incidents of banditry and kidnappings were on the rise. Then what should we do? Rather than a boxed pair of engraved flintlock pistols, fine amber, shiny beads and a bale or two of embroidered cloth, wed barter our lives with a bundle of tatty clothes, a couple of defunct mobile telephones, five deflated footballs and one pump and, in my case, a British passport which declared: Her Britannic Majestys Secretary of State Requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford the bearer such assistance as may be necessary. A quick flash of such a splendid document would surely repel the most determined of plunderers.

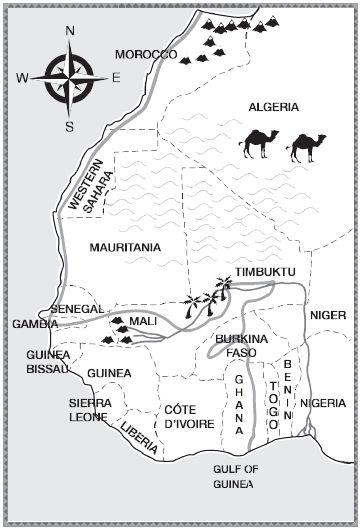

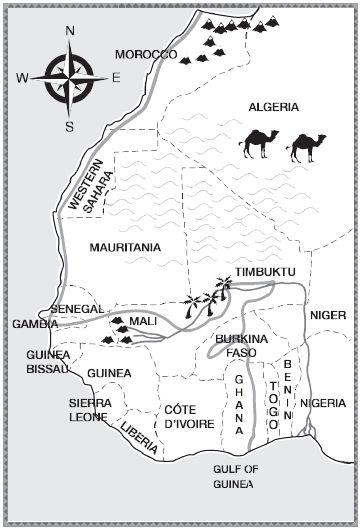

Our journey, from the bustling Tangier of Moroccos north coast, to Tema, a major seaport in southern Ghana, was a very different prospect from what the explorers faced. We had no sponsors to satisfy and no duties to perform. On the contrary, a touch of debauchery behind a distant dune held a certain appeal. And if we didnt find a nugget of goldwellit really didnt matter. We were seeking treasure of an alternative type; adventure, companionship, the pleasure of the open road, unfamiliar cultures, and the magic of participating in arguably one of the worlds most unusual music festivals: the Festival in the Desert.

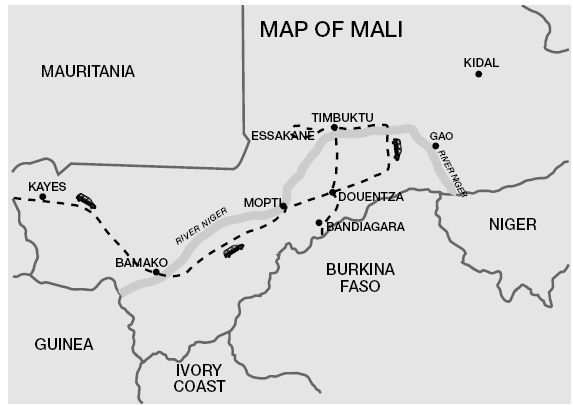

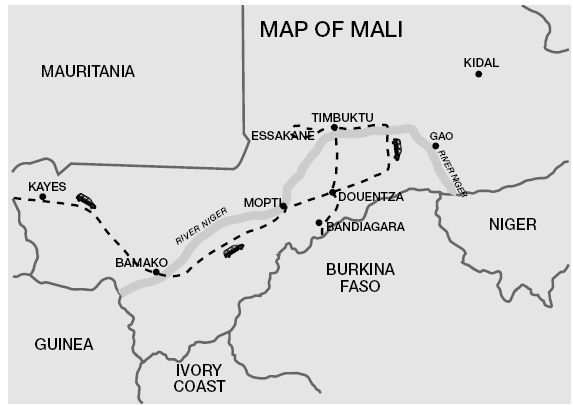

Essakane is sixty kilometres to the west of Timbuktu and has become synonymous with the annually staged Festival in the Desert, an event originally organised by the Tuareg in January 2001. With the Tuareg spread over no fewer than five African countries, the first of these events was a traditional gathering, a celebration of their culture, dance and music, and an opportunity to discuss the challenges they faced. Since the festivals inception some of West Africas leading music artists, including musicians from around the world, have come to play at Essakane. In addition to the music the festival promotes the values of hospitality and tolerance, and is a celebration of peace, even though peace in the Sahara is something of a paradox. Over the previous one hundred years the Tuareg themselves have staged a number of rebellions in their quest for autonomy and an independent state they call Azawad. The rebellious rumblings we experienced during our trip were to erupt into full-scale conflict in 2012, the situation made worse by Islamist insurgents determined to strengthen their grip on the region. All too soon the music in Timbuktu was silenced and the tourists fled. French military intervention dispersed the Tuareg rebels and pushed back the Islamist groups. Whilst stability of a sort has returned to the north of Mali, the country faces a humanitarian crisis and an uncertain future.

The eighteenth century explorers have been described as the first overlanders in West Africa. Today the term overland has been adapted to encompass long-distance, vehicle-based travel and applies equally to the lone cyclist, the individual traveller with their own vehicle, or companies offering multi-itinerary group tours using specially adapted trucks. Starting with the hippy trail in the 1960s, a global business has developed in its wake. Unquestionably, therefore, an overlander must be a person who participates in such a journey. Or so I imagined. But are they? If I was to adopt such a role for the foreseeable future, I felt I should at least acquaint myself with its definition. I reached for the Oxford English Reference Dictionary (second edition, revised), and this is what I found:

overlander: 1. a person who drives livestock overland (orig. one who drove stock from New South Wales to the colony of South Australia).

2. (slang) a tramp, a sundowner.

If the first definition had little relevance to what we were about to undertake, the second one seemed full of promise. A tramp, a sundowner: in other words, a wanderer who likes a stiff drink at the end of the day. The definition fitted the bill perfectly; I felt I could very happily embrace this life of an overlander.

So, to all those itinerant romantics out there CHEERS!

Next page