Contents

Landmarks

FIRST VINTAGE EBOOKS EDITION, OCTOBER 2013

Copyright 2012 by Robert A. Caro, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

This excerpt, in slightly different form, originally appeared in The New Yorker and subsequently as Chapters 11 and 12 in The Passage of Power, published by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2012.

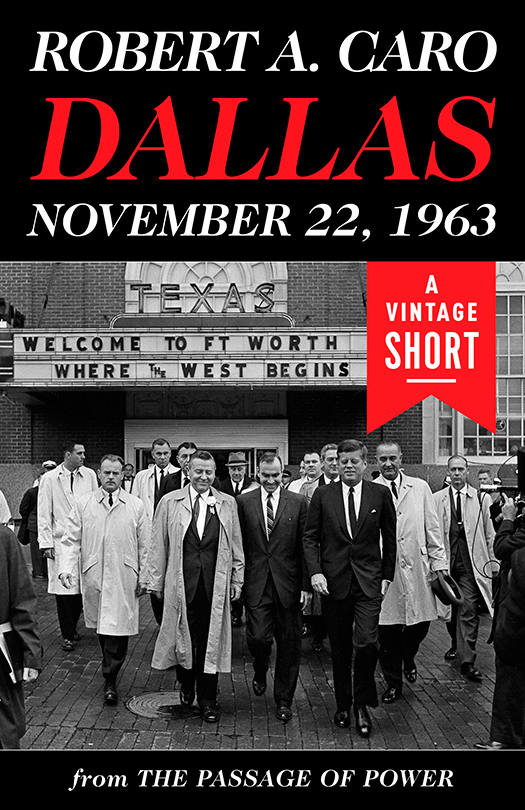

Cover design by Ben Denzer

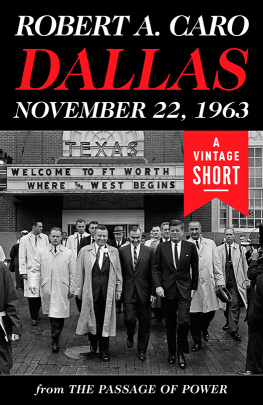

Cover photograph (President John F. Kennedy, with Governor John Connally, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Secret Service Agent Rufus Youngblood, and others, exiting the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth on the morning of November 22, 1963): AP Images

Ebook ISBN9780804171342

www.vintagebooks.com

rh_3.1_139976910_c0_r5

Contents

F RIDAY , N OVEMBER 22, 1963, began for Lyndon Johnson in Fort Worth with the headline he saw on the front page of the Dallas Morning News: YARBOROUGH SNUBS LBJ .

Johnson, accompanying President Kennedy on a tour of Texas, had been given an assignment that the President considered vital: since a unified Democratic front in the state would be needed to carry it in 1964, the Vice President had been made responsible for healing the bitter Democratic Party rift between Governor John B. Connally, a former Johnson assistant, and Senator Ralph Yarborough, the leader of the Partys liberal wing. The previous day, however, Yarborough had refused even to ride in the same car as Johnson. Assigned to accompany the Vice President during a presidential motorcade through San Antonio, the senator had gotten into another car instead, and, in a procession in which the other vehicles behind the presidential limousine were packed with people, Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, had had to sit conspicuously alone in the back seat of their convertible.

Newspapers that day chronicled every detail of Johnsons humiliation. Twice at San Antonio Johnson sent a Secret Service man to invite Yarborough to ride with him in his car. Both times the senator ignored the invitation and rode with someone else, the Los Angeles Times reported. The Chicago Tribune noted the curt wave of his hand with which Yarborough had sent the Vice Presidents emissary packing. The feud was the main story of Kennedys trip not just in Texas but across the country. On the morning of the twenty-second, Lyndon Johnson sat in his suite at Fort Worths Hotel Texas with newspapers in front of himthere were four separate stories in the Dallas paper alone; one was NIXON PREDICTS JFK MAY DROP JOHNSON and then he had to go downstairs for an early-morning rally of five thousand labor union members, and join Kennedy, Yarborough, Connally and some local congressmen, all of whom had of course seen those stories. As they walked across the street to the rally, a light drizzle was falling. Johnson was wearing a raincoat and a hat; Kennedy was bareheaded and lithe in an elegant blue-gray suit. Johnson hastily snatched off his hat. His assignment, as usual, was to introduce Kennedy, and as he finished, the crowd roared for the young man beside him. Explaining why Jackie wasnt there (Mrs. Kennedy is organizing herself; it takes longerbut of course she looks better than we do), Kennedy was easy and charming. Johnson had had to ask Kennedy for a favor: to be allowed to bring his youngest sister, Lucia, and her husband, Birge Alexander, who lived in Fort Worth, to meet him; shaking hands with Kennedy in his suite after the rally, she was thrilled; she had always wanted to shake hands with a President, she said.

When he had gotten dressed early that morning, Kennedy had strapped a canvas brace with metal stays tightly around him and then wrapped over it and around his thighs in a figure-eight pattern an elastic bandage for extra support for his bad back; it was going to be a long day. Now it was nine oclock, time for him to deliver a breakfast speech to the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce in the hotels ballroom. All right, lets go, he said.

N INE O CLOCK IN T EXAS was ten oclock back in Washington. At ten oclock in Washington that Friday morning, at about the same time that Kennedy was entering the Fort Worth ballroom, a Maryland insurance broker named Don B. Reynolds, accompanied by his attorney, walked into Room 312 of the Old Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill to begin answering questions from two staff members of the Senate Rules Committee: Burkett Van Kirk, the Republican minority counsel, and Lorin P. Drennan, an accountant from the General Accounting Office who had been assigned to assist the committee.

Reynolds was there because the Rules Committee had begun investigating a scandal revolving around Johnsons protg Robert G. (Bobby) Baker, whom Johnson, during his years as Senate Majority Leader, had made Secretary for the Majority. During the preceding two months, the scandal had been escalating week by week. In a desperate attempt to head off the investigation, Baker had resigned (he later said that if he had talked Johnson might have incurred a mortal wound by these revelations. They could have driven him from office), but the resignation had only ignited a media firestorm that broke on newspaper front pages across the country and in sensational cover stories in major news magazines. The scandal had thus far concentrated on the man known in Washington as Little Lyndon, but the stories were beginning to focus more and more on Johnson himself. On the Monday of the week that Kennedy left for Texas, a lengthy and detailed article had appeared in Life SCANDAL GROWS AND GROWS IN WASHINGTON , based on the work of a nine-member investigating team headed by a Pulitzer Prizewinning reporter, William G. Lambert. It had gone beyond a recounting of Bakers personal financial saga to make clear that, in distributing campaign contributions and in his other Senate activities, Baker had simply been Lyndons bluntest instrument in running the show. And the focus was about to sharpen that morning. Reynolds, who was Bakers former business partner, had come to Room 312 to tell the Senate investigators about a number of Bakers activities, one of whichthe purchase of television advertising time and an expensive stereo set, in return for the writing of an insurance policyBaker himself later called a kickback pure and simple, to Johnson. On the advice of his attorney, Reynolds had brought with him documentsinvoices and cancelled checksthat he said would prove that assertion. Another of Bakers activities that Reynolds began describing that morning would also turn out to be related to Johnson: an overpayment by Matthew McCloskey, a contractor and major Democratic funder, for a performance bondan overpayment of $109,000 for a bond that had cost only $73,000, with $25,000 of that overpayment, Reynolds later said, going to Mr. Johnsons campaign.

In New York, there was also going to be a meeting that morningof about a dozen reporters and editors in the offices of Lifes managing editor, George P. Hunt. During the past week, reporters who had been sent to Texas to investigate the Vice Presidents finances had found areas ripe for inquiry. For one thing, they had begun searching through deeds and other records of recent land sales and had found that the real-estate and banking transactions of the Johnson familys LBJ Company were on a scale far greater than had previously been suspected. And other reporters were digging into the advertising sales and other activities of KTBC, the cornerstone of the Johnsons extensive radio and television interests, and they, too, were turning up one item after another that they felt merited looking into. With every day that week, the story kept getting bigger and bigger, Lambert said later, and it was no longer a Bobby Baker story but a Lyndon Johnson story: after thirty-two years on the [government] payroll he was a millionaire many times over. But, Lambert said, so many reporters were working in Johnson City, Austin, and the Hill Country that they were tripping all over each other. An article laying out some of their new findings had already been written, by Keith Wheeler, a staff writer. A decision had to be made on whether to run his story in the magazines next issue or whether the material already in hand should be held until more was available, and combined into a multi-part series on Lyndon Johnsons Moneywhat Lambert termed a net worth joband a meeting to decide this, and to divide up the areas of investigation in Texas, had been scheduled for 11:30 A.M. on November 22.