This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOR INA

and for DR. JANET G. TRAVELL

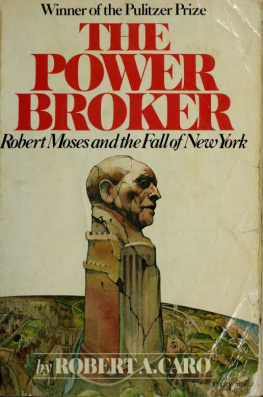

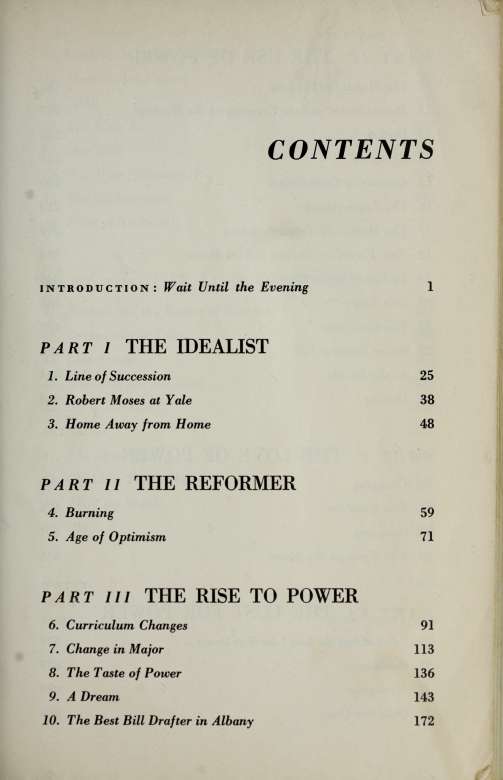

part IV THE USE OF POWER

11. The Majesty of the Law 181

12. Robert Moses and the Creature of the Machine 207

13. Driving 226

14. Changing 241

15. Curator of Cauliflowers 260

16. The Featherduster 283

17. The Mother of Accommodation 299

18. New York City Before Robert Moses 323

19. To Power in the City 347

20. One Year 368

21. The Candidate 402

22. Order Number 129 426

23. In the Saddle 444

24. Driving 468

part v THE LOVE OF POWER

25. Changing 499

26. Two Brothers 576

27. Changing 607

28. The Warp on the Loom 615

part vi THE LUST FOR POWER

29. "And When the Last Law Was Down ..." 639

30. Revenge 678

31. Monopoly 689

32. Quid Pro Quo 699

Contents

33. Leading Out the Regiment

34. Moses and the Mayors

35. "RM"

36. The Meat Ax

37. One Mile

38. One Mile (Afterward)

39. The Highwayman

40. Point of No Return

IX

755 807 837 850 885 895 920

part vii THE LOSS OF POWER

41. Rumors and the Report of Rumors 961

42. Tavern in the Town 984

43. Late Arrival 1005

44. Mustache and the Bard 1026

45. Off to the Fair 1040

46. Nelson 1067

47. The Great Fair 1082

48. Old Lion, Young Mayor 1117

49. The Last Stand 1132

50. Old 1145

NOTES

1163

INDEX

PHOTOGRAPHS

section i follows page 146

section ii follows page 562

section in follows page 978

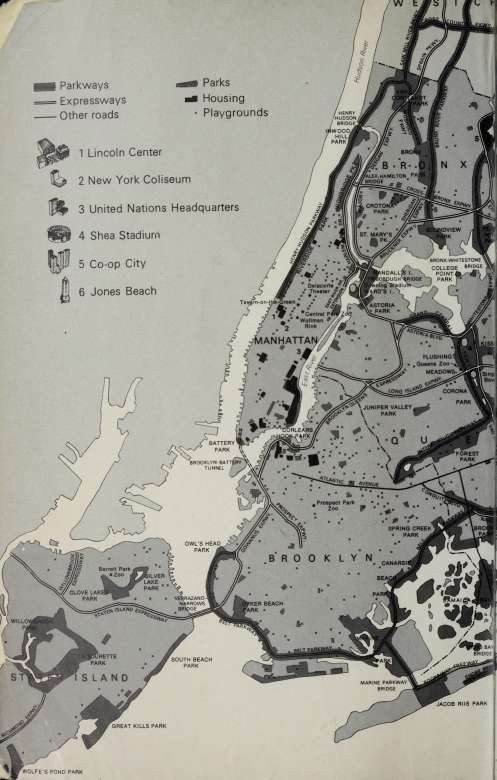

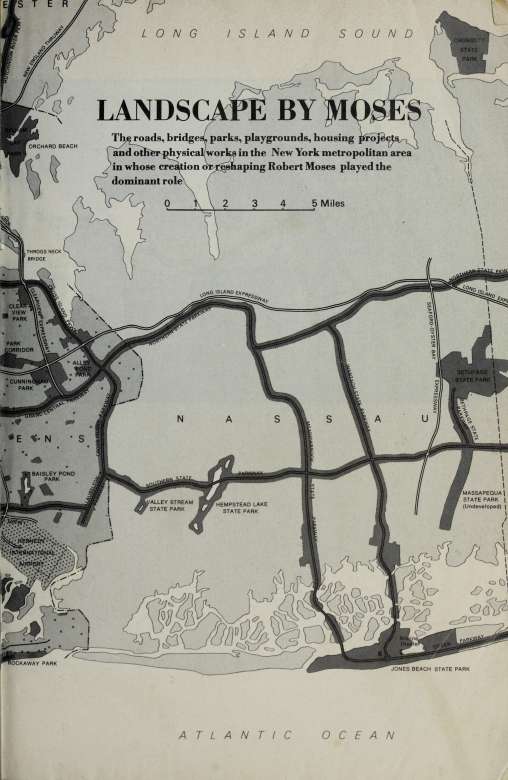

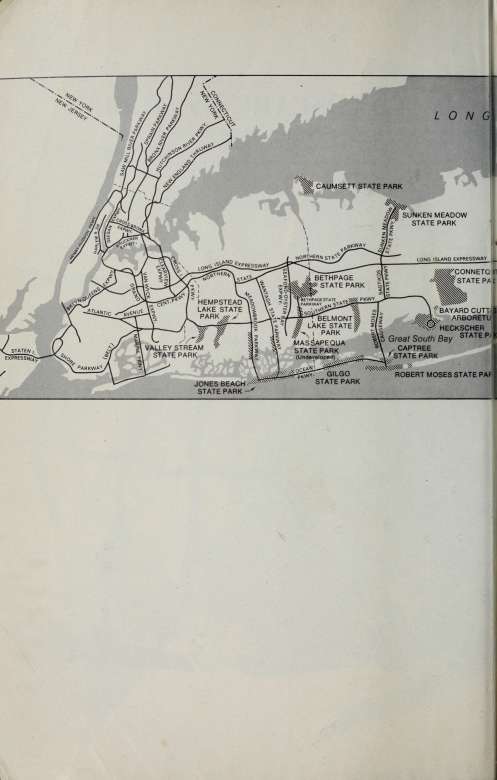

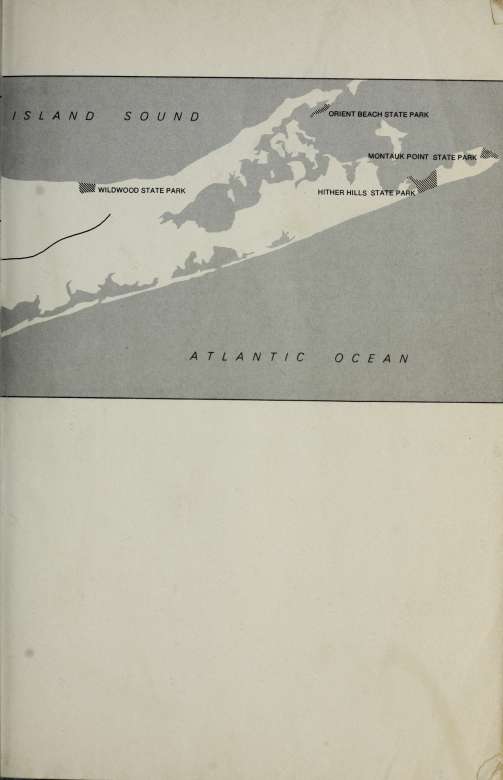

MAPS

landscapes by moses ii-iii

ROBERT MOSES' PROPOSED

NORTHERN STATE PARKWAY 164-5

DETOUR FOR POWER 302-3

ORCHARD BEACH: BEFORE AND AFTER 366

THE TRIBOROUGH BRIDGE COMPLEX 388

THE ONE MILE 864

NEW YORK STATE PARKS XXXviii-XXxix

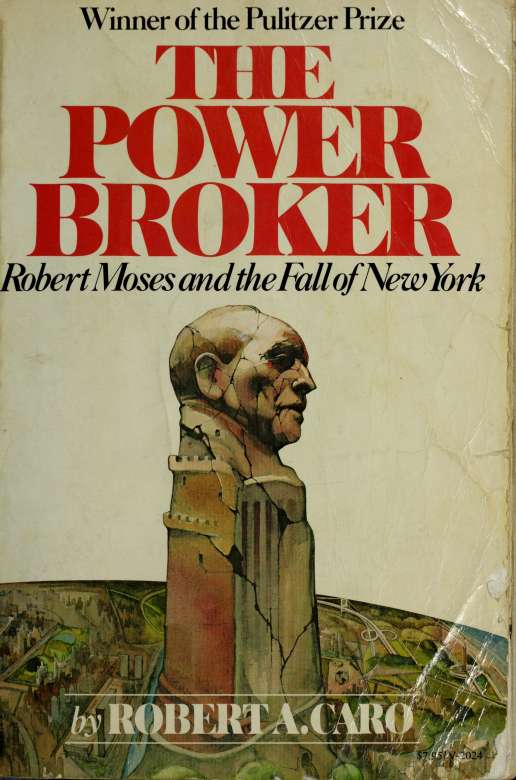

THE POWER BROKER

INTRODUCTION Z

was no money to replace the dank, low-ceilinged pool, which wasn't even the right length for intercollegiate swimming events. There was no allocation from the university for travel expenses or even for a coach. But Reid, who had been Yale's first great swimmer, not only paid the team's expenses but, week after week, traveled up to New Haven from New York to do the coaching himself. This year, after a long fight, Moses had succeeded in organizing the wrestling, fencing, hockey, basketball and swimming teams into a "Minor Sports Association" which would conduct a general fund-raising effort and divide the money among the teams, in the hope that the existence of such a formal organization would coax new contributions from alumni. The theory was good, Richards had thought at the time, but there was one hitch: any money contributed specifically to one of the teams also had to go into the general fund. Richards doubted that Reid, who was interested only in swimming, would want to contribute to a general fund and he wondered if the swimmers might not end up with even less money than before. But Moses had seemed to have no fears on that score. And now, standing beside the pool, Richards was beginning to understand why. Moses, dressed in suit, vest and a high collar that was wilting in the dampness, had just announced that he was skipping practice to go to New York and see Reid, and when Richards had expressed his doubts that the alumnus would contribute, Moses had smiled and said, "Oh, that's all right. I just won't tell him it's going to an association. He'll think it's the regular contribution to the swimming team."

Now Richards said slowly, "I think that's a little bit tricky, Bob. I think that's a little bit smooth. I don't like that at all."

With astonishing rapidity, the face over the high collar turned pale, almost white. Moses' fists came up for a moment before he lowered them. "Well, you've got nothing to say about it," he said.

"Yes, I do," Richards said. "I'm the captain. I'm responsible. And I'm telling you not to do it."

"Well, I'm going to do it anyway," Moses said.

"If you do," Richards said, "I'll go to Og and tell him that the money isn't going where he thinks it is."

Moses' voice suddenly dropped. His tone was threatening. "If you don't let me do it," he said, "I'm going to resign from the team."

He thought he was bluffing me, Richards would recall later. He thought I wouldn't let him resign. "Well, Bob," Richards said, "your resignation is accepted."

Bob Moses turned and walked out of the pool. He never swam for Yale again.

Forty-five years later, a new mayor of New York was being sworn in at City Hall. Under huge cut-glass chandeliers Robert F. Wagner, Jr., took the oath of office and then, before hundreds of spectators, personally administered the oath, and handed the coveted official appointment blanks, to his top appointees.

But to a handful of the spectators, the real significance of the ceremony

was in an oath not given. When Robert Moses came forward, Wagner swore him in as City Park Commissioner and as City Construction Coordinator and then, with Moses still waiting expectantly, stopped and beckoned forward the next appointee.

To those spectators, Wagner's gesture signaled triumph. They were representatives of the so-called "Good Government" organizations of the city: the Citizens Union, the City Club, liberal elements of the labor movement. They had long chafed at the power that Moses had held under previous mayors as Park Commissioner, Construction Coordinator and member of the City Planning Commission. They had determined to try to curb his sway under Wagner and they had decided to make the test of strength the Planning Commission membership. This, they had decided after long analysis and debate, was Moses' weak point: As Park Commissioner and Construction Coordinator he proposed public works projects, and the City Charter had surely never intended that an officeholder who proposed projects should sit on the Planning Commission, whose function was to pass on the merits of those projects. For nine weeks, ever since Wagner's election, they had been pressing him not to reappoint Moses to the commission. Although Wagner had told them he agreed fully with their views and had even hinted that, on Inauguration Day, there would be only two jobs waiting for Moses, they had been far from sure that he meant it. But now they realized that Wagner had in fact not given Moses the third oathand the Planning Commission job. And, looking at Moses, they could see he realized it, too. His face, normally swarthy, was pale with rage.