Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2019 by Christopher Verga

All rights reserved

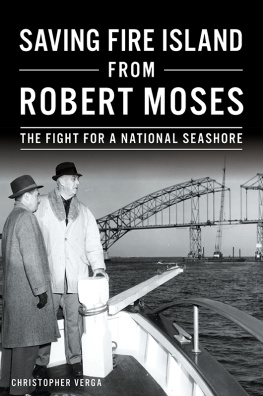

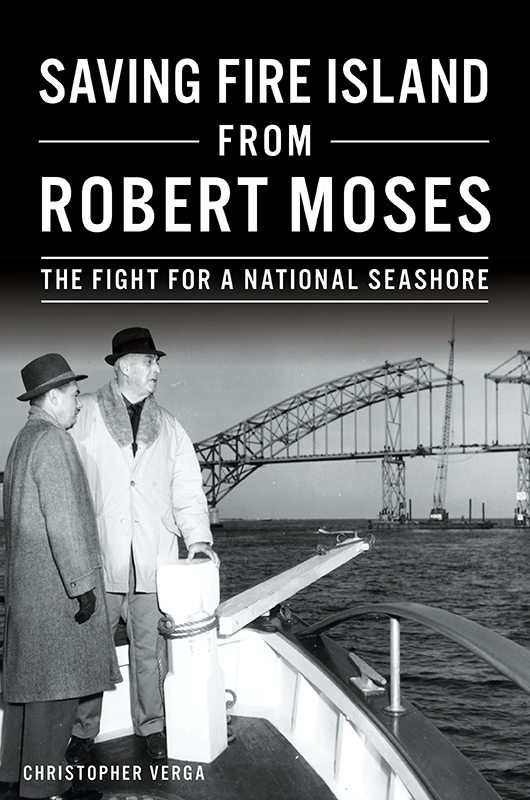

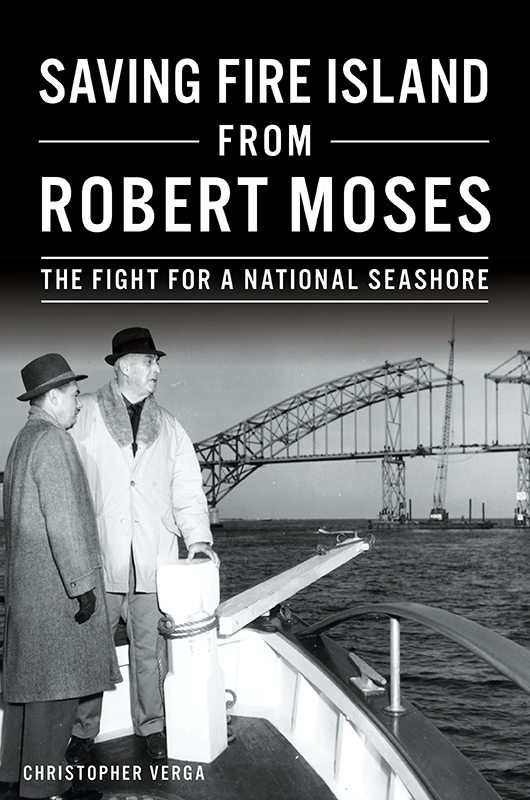

Front cover: Robert Moses (at left) and Babylon town supervisor Arthur Cromarty inspecting the construction of the Fire Island Inlet Bridge. Town of Babylon Office of Historic Services Image Collection.

First published 2019

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.643.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018963594

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.034.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No one person can own or monopolize the history they write or interpret. The gatekeeper to our history lies in the collective efforts of a community to keep it alive. Whomever we recognize as heroes or villains are defined as such by the impact they had on a community they represented. One persons hero can be another persons villain and vice versa. Robert Mosess undisputable impact was that he opened Long Island for suburban development, but Moses overlooked the environmental impacts onand the destruction ofthe regions traditional seaside communities. Diverse perspectives and resources are needed from various communities to tell this story.

This book would have not been possible without the support of Lillian, Susan and Catherine Barbash and Irving Like. Their interviews, pictures and documents helped me reconstruct the challenges and events that created a more environmentally conscious Long Island. The power of civics and citizen activism demonstrated by the Barbash and Like families created an organized, community-wide grassroots movement that is duplicated throughout the county. The Fire Island National Seashore, enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of people every year, will always be a testament to the legacy of the Barbash and Like families.

Special thanks to Lee Koppleman, who devoted hours of interviews to make this project successful. Koppelmans legendary accomplishments are ingrained in his creations of Suffolk County Community College, Suffolk Countys Environmental Bill of Rights, Blydenburgh Park and Gardner Park. His lifetime work in attempting to create balance between economic development and conservation paved the way for grassroots activists to achieve success within the dawn of the environmental movement.

Special thanks to Mary Cascone and the Town of Babylon Office of Historic Services for sharing the images of Robert Moses, early barrier beach communities and construction of the Robert Moses Bridge. I would like to express my gratitude for the images of the construction of Jones Beach provided by Dr. Geri Solomon and Hofstra University Special Collections. These images are the backbone upon which the retelling of an almost forgotten history and heritage of Long Island is built.

I would like to extend special recognition to all the local historians I consulted with at the Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society, Bay Shore Historical Society, Babylon Village Historical Society, Nassau County Historical Services, Seatuck Environmental Association and Suffolk County Historical Society.

INTRODUCTION

Tranquil shorelines of sun-washed sands cover the turbulent history of man trying to dominate the elements of nature. The conflict of man versus nature is central to the argument of finding a balance between conservation and economic development. Through the limited resources bestowed upon inhabitants, conflict will batter ordinary people into ignominious obscurityor turn them into legends. Unchecked political power and futuristic visions of a modern suburbia will collide with a bygone era struggling to hang on despite the changes created through fast automobiles and superhighways. Grassroots activism, pioneered in the 1960s to keep Fire Island environmentally and culturally intact, will become the catalyst for the modern-day environmental movement throughout Long Island and sink the career of the most revered man in New York State government, Robert Moses.

Fire Islands estimated thirty-two-mile length, and its width of over a half-mile at its widest point, keep nearly all resources in short supply. Despite its limits, the island provides unlimited tranquility for the 500,000 people who vacation on it each year. Able to endure the worst hurricanes ever to hit New York, the island was almost unable to withstand suburbia. With the 1962 Atlantic hurricane season fresh in the memories of mainlanders, coastal flooding became a central topic in the debate about planning for suburban development. The misconception that accessibility created by automobiles could democratize the natural beauty of South Shores estuaries posed a threat to the rustic landscape and fragile balance of preservation. Fire Island as we know it today could have been a four-lane highway connecting Ocean Parkway to Montauk Highway in Montauk.

An estimated 450,000 cubic yards of sediment transported over 3,500 years of longshore drift steadily expanded into an isthmus that, by connecting current Fire Island to the Long Island town of Quogue, joined the islands into a peninsula. The effect of these waves is the erosion of the sediment from the shore and shifting shorelines. Diverse sediments created various vegetation habitats that include salt marsh, trees, shrubs and coastal plain vegetation such as beach grass. Over 300 years ago, Sunken Forest was created through the formation of two sets of dunes. This forest includes holly trees, cherry trees, black oak trees and sassafras.

An estimated ten thousand years ago, ancestors of present-day Native Americans migrated to and established a civilization across Long Island. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Dutch and English colonists classified the aboriginal residents of Long Island into thirteen tribes: the Canarsee, Rockaway, Merrick, Marsapeague, Secatogue, Unkechaug, Matinecock, Nesaquake, Setalcott, Corchaug, Shinnecock, Manhasset and the Montauks. These classified tribes shared a network of kinships and trade between most Southern New England Algonquin-speaking nations. These original Natives who had encountered Fire Island had already named the two sections of the island Seawanauke, translated to land of shells, and Paumanauk, meaning land of tribute. In settler William Tangier Smiths survey, exploration records and notes, eastern sections of Fire Island were described as marshlands connecting mainland Long Island to the barrier island. These marshlands allowed Natives access to Fire Island to harvest its marine resources. The most valuable of the resources the Natives harvested from the island was shellfish, not only for eating, but also for the shells, which were used as wampumthe main currency traded among the Northeastern Native tribes. Fire Island also provided access to the oceans abundant hunting ground for whales. Natives would feed on the beached whales stranded on sandbars or hunt them off the coast. After the whale hunts, Natives would light fires signaling inland natives for more supplies or communicating the bounty they had harvested. In the shallower waters, Natives depended on menhaden, a fish used as fertilizer for the growing of vital crops. Production of wampum and menhaden made the local Long Island tribes stable political structures wealthy through trade of resources harvested from Fire Island. The successful harvests of these abundant resources were due to the balance of conservation and consumption.

Next page