ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to many people for help with this book.

My colleague Bob Christina helped enormously with ideas and information about the development of motor skills. Bob teaches in North Carolina, at the Pinehurst Golf Academy in Pinehurst and at Robert Linvilles Precision Golf School in Greensboro. Any golfer could benefit from spending time with Bob Christina.

Its been my privilege to work with many of the worlds greatest golfers over the years. Several of them were especially helpful for this book. Trevor Immelman, Graeme McDowell, Mark Wilson, Darren Clarke, Peter Uihlein, Pat Bradley, and Keegan Bradley were generous with their time and their memories. Tom Kite, Padraig Harrington, Davis Love III, David Frost, and Brad Faxon have been more than clients over the years; theyve been friends. Id like to thank some of my clients from the amateur ranks for their help, particularly Marty Jacobson and Gary Burkhead. Ive learned from every player Ive worked with, and what Ive taken from them is in the pages of this book. Thanks to them all.

My literary agent, Rafe Sagalyn, and my editor, Dominick Anfuso, have been genuine partners for seventeen years, as they were on this project.

And, finally, none of what I do would be possible without my wife, Darlene.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

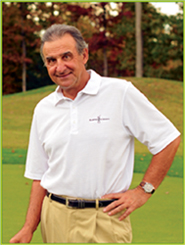

D r. Bob Rotella is one of the worlds preeminent sports psychologists and performance coaches. He specializes in helping golfers overcome their mental challenges. Golfers coached by Bob Rotella have won a total of 74 major championships. He has also helped athletes in tennis, baseball, basketball and other sports as well as singers and business leaders.

Dr. Rotella got his bachelors degree from Castleton State College in Vermont and his doctorate from the University of Connecticut. He was the Director of Sports Psychology at the University of Virginia for 20 years, a period in which he helped the Cavaliers football and basketball programs rise from decades of losing seasons to participation in bowl games and NCAA tournaments. He and his wife, Darlene, live in Virginia.

B ob Cullen is a journalist and writer. During the years he has collaborated with Dr. Bob Rotella, his golf handicap has gone from 21 to 5. He lives with his wife, Ann, in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Dr. Bob Rotella was the Director of Sports Psychology for twenty years at the University of Virginia, where his reputation grew as the person champions talked to about the mental aspects of their game. His client list includes Hall of Fame golfers like Pat Bradley, Tom Kite, and Nick Price as well as stars of the present such as Sean OHair and Trevor Immelman. A writer for and consultant to Golf Digest, he lives in Virginia with his wife, Darlene.

Visit www.drbobrotella.com

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS

JACKET DESIGN BY ERIC FUENTECILLA

FRONT JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY COMSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

BACK JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BOB CULLEN

COPYRIGHT 2012 SIMON & SCHUSTER

ONE

THE SHORT GAME AND WINNING GOLF

By learning how to get the ball up and down, you will have mastered the art of scoring your best.

Tom Watson

U nstoppable golf and a great short game are inseparable. If I didnt already know this, I could learn it every April at the Masters.

In the popular mind, Augusta National Golf Club may be a course that Bob Jones and Alister MacKenzie designed to favor the heroic long hitter, a Sam Snead when the Masters began or a Bubba Watson today. And theres certainly nothing wrong with hitting the ball a long way, especially if a golfer hits it where hes aiming. Only a fool would say hed rather not drive the ball 330 yards into the middle of every fairway.

But Ive seen lots of players who can drive the ball 330 yards and yet have never won a Masters, or even come close. Augusta National tests their short games and finds them wanting.

All the grass on and around Augustas greens is mowed closer than the hair on the head of a boot-camp marine. The greens are so quick that inexperienced players can and do putt right off of them. And the putts on the greens are not nearly as testing as the pitches around them. From grass so short that most golf clubs would be happy to call them putting surfaces, players have to hit pitches and lobs that fly precise distances at precise trajectories and then either check up or roll out, depending on the circumstances. Moreover, the grounds crew at Augusta generally mows so that the golfer has to chip and pitch into the grain of the grass, adding another layer of complexity for the elite player.

These conditions expose a lot of doubt and fear. No one gets invited to the Masters unless he is an accomplished player. But I have had Masters contestants come up to me in the days before the tournament begins and say, No way am I getting in the hunt this week, Doc. I am not going to pitch the ball from around these greens on national television.

Thats an extreme example of the debilitating fear that can infect a golfers short game. At other times, the effect is more subtle.

A young player I work with was thrilled one year to be invited to his first Masters. For the most part, he played very well, but he missed the cut by a stroke or two. One of his playing partners during the first two rounds sent me a message about my client. The message was: Hes a good kid and a good player. But he needs to be able to hit a high, soft lob off a tight lie.

The truth was, my young client could hit a high, soft lob off a tight lie. But when he got to the Masters for the first time, he felt a sudden flash of doubt when the need for that shot arose, as it inevitably did. Mentally, he wasnt quite ready to play the short game that Augusta National demands. He played other kinds of shots in those situations, shots from a ball position closer to his right foot, so he could be confident of striking the ball cleanly. They probably looked quite decent to the average spectator, but these shots too often didnt get him close enough to the hole to save par or make birdie.

Physically, he was ready to play in the Masters. He had the skills. But my client still had work to do to develop the mental side of his short game. He had, quite understandably, felt a little bit in awe of the Masters. That had caused him to start to feel that he had to be able to hit perfect shots to compete there. He forgot that on lots of very good golf courses, hed won because hed trusted his skills and let himself find a way to get the ball in the hole.

The player who wins at Augusta loves the way the course challenges his short game. He loves showing off his skills. He loves knowing that his short game will separate him from many of the other contestants.

Trevor Immelman, who won the Masters in 2008, is a perfect example. Trevor learned the short game very naturally, the way I would hope any kid would learn it. He has a brother, Mark, whos nine years older and himself a very good golfer (and now the coach at Columbus State University in Georgia). Mark took up the game at fourteen, when he enrolled at a school called Hottentot Holland High School in the Immelmans hometown of Somerset West, South Africa. Trevor, who was five, tried desperately to keep up with Mark and his friends. Obviously, he couldnt hit the ball as far as his older brother. Out of necessity, he learned to hit pitches close to the hole and to putt well.

The boys father, Johan, responded to his sons passion for golf by building a rudimentary putting green with a sand bunker in the familys front yard. Neither Johan nor Mark had to force Trevor to use the green. Trevors competitive instincts got him started. He remembers that sometimes he would practice his chips, pitches, and putts for hours at a time. Sometimes he would do it in spurts, practicing for fifteen or twenty minutes, then going back inside the house and watching television. Eventually, he expanded his horizons, hitting pitches to the green from neighbors lawns. Some of them were a full wedge away and Trevor learned to hit over trees and walls. (Somerset West must have been a kind and tolerant community.)

Next page