I have a St Kilda in my mind, an island haven reminding me,

You are a Scot. Do not forget that fact.

Tom Steel, Notes on St Kilda

Tom Steel died on 21 July 2007; he was sixty-three years old. Tom first wrote The Life and Death of St Kilda when he was a student at Cambridge. It was published by the National Trust for Scotland in 1965, and subsequently by Fontana in 1975, with a new edition in 1988. When he died, Tom had been working on material for an update to the 1988 edition. The Postscript to this book is based on those notes, and goes on to include what has happened to St Kilda since 2007.

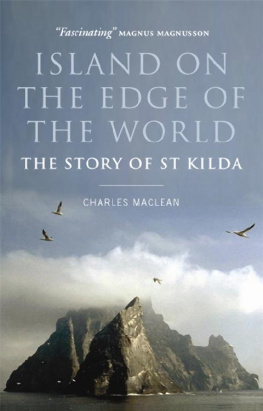

The destiny of St Kilda has been defined largely by two events. The first was on 29 August 1930 when its inhabitants were evacuated. The other was in 2005 when St Kilda received a second UNESCO World Heritage Site designation, making it the only Dual World Heritage site in the United Kingdom.

Although official recognition from the UN of St Kildas natural, marine and cultural significance should give it protection from oil exploitation, vandalism, fishing hazards and damage to its wildlife and terrain, there is little legally that the responsible authorities, which include UNESCO, the European Union, the Scottish Parliament and the UK government, can do to safeguard the islands. Tom believed the future safety of St Kilda would lie in its at-times-inaccessible position. The seas and the weather of St Kilda remain as much a threat to visitors as they have always been. Shipwrecks still happen and access is often cut off.

There is a moral obligation to ensure that the National Trust for Scotland, which owns and manages the islands on behalf of the Scots and the rest of the world, receives the financial and public support to enable it to protect St Kilda. Therein lies a dilemma. The Scottish Parliament has a right to roam policy, one which is endorsed by the NTS, whose own open access strategy encourages people to visit its properties. The NTS needs to raise the islands profile to attract visitors and funds to enable it to maintain a presence. At the same time, it has to guard against too many visitors causing damage to the environment, which has happened at other World Heritage Sites such as Macchu Pichu, the Galapagos Islands, and the Cairngorms in Scotland.

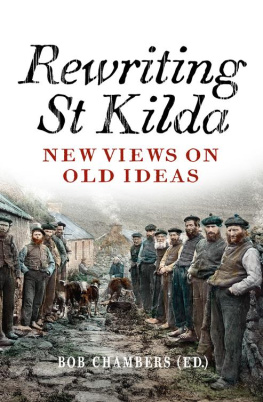

In 1930 the departing St Kildans left their doors open believing that no one would ever live on Hirta again. In August 2010 there were thirty-six people on St Kilda, exactly the same number as had been present eighty years earlier. These were the new St Kildans wardens, members of conservation and archaeological work parties and MOD personnel. In 1988 Tom Steel wrote: Many from the mainland have now experienced what it is like to live on Hirta and it is interesting to compare and contrast our modern reactions to the problems posed by nature. Men now live on St Kilda for different reasons and in a totally different way: but their experiences, nevertheless, and the draw that the archipelago has on our minds and hearts, are worthy of investigation.

Lessons are still being learnt from what happened to St Kilda and to its inhabitants. The islands have been subjected to intensive scientific, historical and archaeological surveys, which may help answer many questions. The constant search for information will, one day, however, draw to an end, leaving the archipelago to return to the wild.

St Kilda continues to affect those who visit it, read or see films about it. The contribution of the stories of the St Kildans and their music is now seen as integral to Gaelic culture. But to Tom, the story of St Kilda was essentially that of its people; a civilization that came to an end because it was more expedient for the authorities to move them rather than give support and enable them to stay. As people examine their lives and relationship with nature, far more is being done to ensure that other such populations faced by extinction remain on their islands. The evacuees always referred to their love and desire to return to St Kilda. It was a far better place, as Malcolm Macdonald once explained to Tom.

Tom Steel first visited St Kilda when he was seventeen, his interest being stimulated as a boy by his father who made several trips to St Kilda on National Trust cruises. The spell that the islands and its people cast on him was to last for the rest of his life.

St Kilda is the most spectacular of all Britains offshore islands. The main island of the group, Hirta, boasts the highest cliffs and the largest colony of fulmars in Britain. The neighbouring island of Boreray and her two rocks of Stac Lee and Stac an Armin are the breeding grounds of the worlds largest colony of gannets. The little archipelago, in fact, is a land of superlatives and as such has always fascinated the minds of men.

But the greatest fascination is that for over two thousand years man lived upon St Kilda. On the island of Hirta people once led a unique and unchanging way of life. They were crofters, like most of their neighbours in the Hebrides, but crofters with a difference. Cut off from the mainland for most of their history, the islanders of Hirta had a distinct way of living their lives. Isolated from the majority of the Scottish people the St Kildans were forced to feed upon the flesh of the tens of thousands of sea birds that returned year after year to breed on the rocky islands. Moreover, their very self-sufficiency meant that throughout their history they possessed a sense of community that was to show itself increasingly out of place.

It is not easy to imagine the lonely life led by the St Kildans. It is difficult for us to accept that they had more in common with the people of Tristan da Cunha than they ever had with the city dwellers of Edinburgh or Glasgow. Any similarity between the St Kildan way of life and that led upon the mainland was superficial. Isolation had a determined effect upon their attitudes and ideas. The St Kildans can only be described as St Kildans and their island home little else than a republic. The people, like those of most isolated communities, sacrificed themselves year in and year out securing, often precariously, a livelihood for themselves and their children. In the practical business of living, St Kilda bore little relation to the mainland where people were becoming more concerned with evading secondary rather than primary poverty. When the island was finally evacuated in 1930, not only had Nature defeated man but, in a real sense, man had defeated his fellow men.

Now, over fifty years after the evacuation, the whole story can be told, and in particular what happened to the St Kildans after they decided to abandon Hirta and settle on the mainland of Scotland. It was not until 1968 that the records of the Scottish Office pertaining to the 1930s were made available to public examination. In the Public Records Office in Edinburgh lie more than two dozen files that once were the property of the Department of Agriculture. From the collection of letters, minutes, and memoranda can be gleaned the true tragedy of the evacuation not only the human distress involved, but the parsimony and bureaucratic behaviour of the civil servants concerned in the event behaviour which makes one question whether they can ever be capable of true compassion.