Charles Maclean

S T K I L D A

Island on the Edge of the World

AFTERWORD BY

Margaret Buchanan

the isle of Irte, which is agreed

to be under the Circius and on the margine

of the world, beyond which there is found

no lands in these bounds.

John of Fordun

Contents

First Plate Section

St Kildans with telescope National Trust for Scotland ; St Kilda from the east Eric and David Hosking ; View of Stac Lee from Boreray; Stac Lee from the east Robert Atkinson, courtesy of the School of Scottish Studies ; Village Bay Eric and David Hosking ; Euphemia MacCrimmon, the poetess School of Scottish Studies ; Married women c . 1980 National Trust for Scotland ; Fowlers relaxing at the cliffs edge National Trust for Scotland ; Selling souvenirs to tourists Caledonian Newspapers ; Finlay MacQueen, his son and grandson in 1927 National Trust for Scotland ; A St Kilda fowler Niall Rankin, courtesy of Eric and David Hosking ; Finlay MacQueen talking to John Mackenzie National Trust for Scotland ; Spinning, St Kilda; Cill-Chriosed, the graveyard on Hirta National Trust for Scotland ; Rachel MacCrimmon National Trust for Scotland ; Rev. John Mackay School of Scottish Studies ; Bird-fowling on cliffs Eric and David Hosking ; Interior of the church Robert Atkinson, courtesy of the School of Scottish Studies ; Church and manse Caledonian Newspapers ; The St Kilda Parliament National Trust for Scotland ; Woman knitting National Trust for Scotland ; Man with sack of wool National Trust for Scotland .

Second Plate Section

St Kildan schoolchildren George Washington Wilson collection , Aberdeen University Library Ref. C4251 ; Two St Kildan children National Trust for Scotland ; Sending a letter by St Kilda mailboat Robert Atkinson, courtesy of the School of Scottish Studies ; Dividing the fulmar catch c . 1890 National Trust for Scotland ; An artists impression of fowling in 1891 A. Jobling, National Trust for Scotland ; St Kildan children c . 1910 National Trust for Scotland ; Rachel Anne Gillies National Trust for Scotland ; Neil Ferguson and Donald MacQueen grinding corn in a quern National Trust for Scotland ; A view of cleits; Village Bay National Trust for Scotland ; The Gillies family outside their cottage c . 1890 National Trust for Scotland ; Bales of tweed ready for export Caledonian Newspapers ; St Kilda puffins National Trust for Scotland ; Fulmar Petrel National Trust for Scotland ; Gannet with young guga National Trust for Scotland ; Wren National Trust for Scotland ; Soay sheep National Trust for Scotland ; St Kilda field-mouse National Trust for Scotland ; Gannet in flight National Trust for Scotland ; Preparing for evacuation Caledonian Newspapers ; The village main street as it is today National Trust for Scotland .

When a simple or primitive society comes into contact with civilization it undergoes cultural change. Unable to resist the seductive advantages of a more developed technology, it also embraces or has forced upon it a new system of values which inevitably leads to the breakdown of the old culture. This process of acculturation can be seen today as instrumental not only in the destruction of large numbers of simple societies in under-developed parts of the world, but also as a cause of social and environmental problems in the increasingly homogeneous wasteland of modern civilization. It is illustrated here in microcosm by the story of the remote Hebridean island of St Kilda.

A part of Britain but a world apart, St Kilda society existed in almost complete isolation from the mainstream of civilization for more than a thousand years. Increased contact with the mainland during the 19th century brought about the slow downfall of what many had once regarded as an ideal society. In 1930 the islanders who could no longer support themselves, were finally evacuated at their own request.

The history of St Kilda exists by virtue of those visitors, who by going to the island helped to give it a history in the first place and by writing about it afterwards recorded what would otherwise have been lost. Since the St Kildans themselves were mostly illiterate until the turn of the century, their story is chiefly told by outsiders, who, however unwittingly, contributed to the destruction of the island society by breaking its isolation. But without them there would have been no story to tell.

The man whose pen first made St Kilda famous was undoubtedly Martin Martin, the gentleman from the Isle of Skye, hired as literary tutor to the MacLeods of Dunvegan. Martin, who travelled extensively among the Western Isles of Scotland and wrote about most of them, visited St Kilda in 1697. His account of the islanders and their way of life in A Late Voyage to St Kilda is a brilliant and individual piece of reportage displaying keen powers of observation and, in spite of Dr Johnsons assertions to the contrary, a distinct literary gift. Martins work provided the later authors of St Kilda with a source of inspiration, unique information about the island and set a high level of achievement. A few of his successors, like the Rev Kenneth Macaulay, a minister from Ardnamurchan and a great uncle to the famous historian, who was sent to St Kilda in 1758 as a missionary, managed to write close to Martins standard. Each successive publication about St Kilda (there has been a surprising number) has nonetheless added to the sum total of knowledge on the subject in one way or another and will no doubt continue to do so. In the present book I have drawn information and quoted liberally from many of St Kildas authors especially Martin and Macaulay, to whom I am widely indebted.

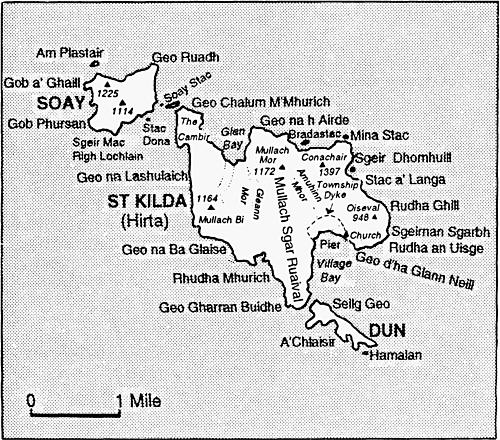

After the evacuation of St Kilda the owner, Sir Reginald MacLeod, sold the island in 1932 to the Marquis of Bute, who as an eminent ornithologist was particularly interested in preserving it as a bird sanctuary and bequeathed it on his death to the National Trust for Scotland. The island has since been made a nature reserve and is leased by the Trust to the Nature Conservancy, who are making an ecological survey of the wildlife, noting any changes that have occurred since the departure of the islanders. During the summer months the National Trust runs cruises to St Kilda and organizes parties to go out and spend a fortnight or so living in three restored cottages on the island and work at the repair and restoration of the buildings, cottages, cleits, dykes and other remains of St Kildan civilization. Eventually they hope to reclaim the entire village from what would otherwise be certain devastation by wind and weather. In 1957 a small area on Hirta was commandeered by the Ministry of Defence for a missile tracking station. A few years ago 500,000 was spent on lengthening the pier in Village Bay and erecting new buildings for a military camp, which surprisingly has been quite well landscaped. It is ironical nonetheless that so much money and effort should have been made available for this purpose forty years after the islanders were evacuated.

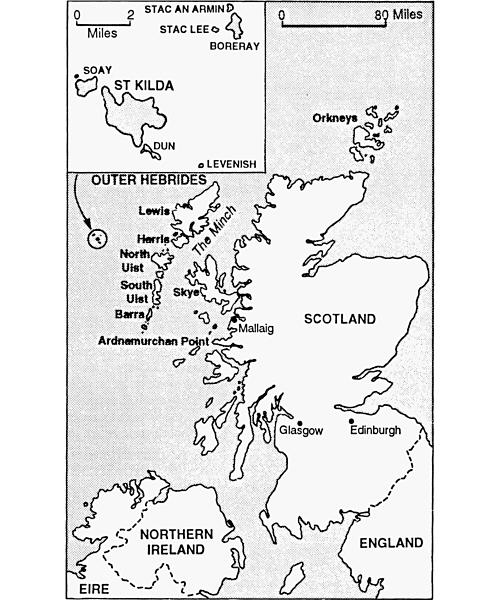

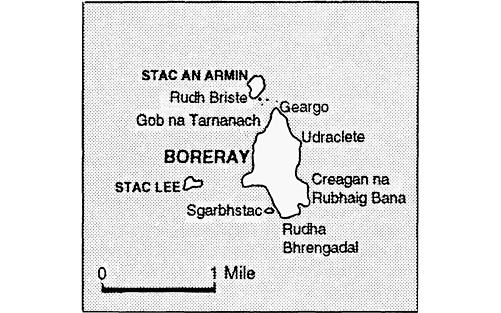

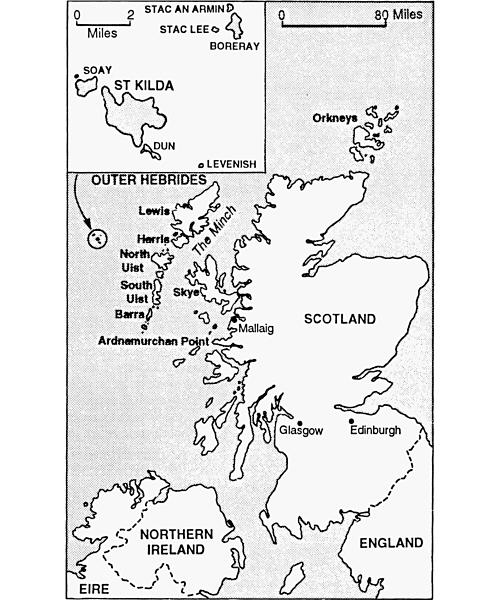

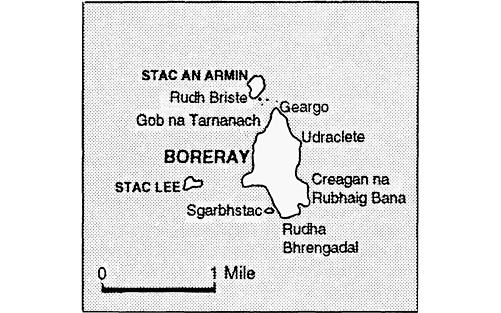

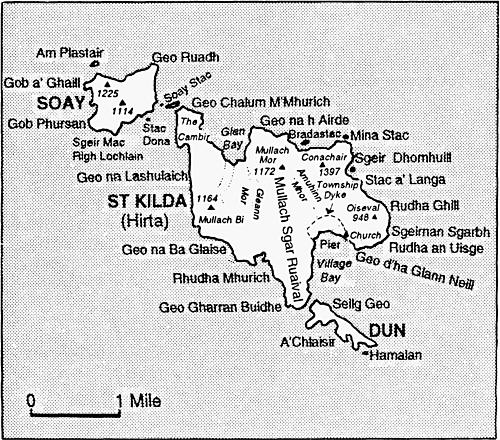

Finding the archipelago of St Kilda on the map is not always easy. A map of Scotland which includes the Outer Hebrides, will often leave out St Kilda because it cannot be fitted on to the page and is too small to qualify for an inset of its own. The island group, comprising four islandsHirta, Soay, Boreray and Dun (Hirta, also known as St Kilda, is much the largest)lies out in the Atlantic Ocean on the edge of the continental shelf, about fifty miles due west of Harris and 110 miles west of the nearest land on the mainland. Its isolation is increased by the difficulties of getting there. Until the 19th century the voyage involved several days and nights in an open boat rowed by MacLeods men from Skye. Once beyond the relative safety of the Minch they were at the mercy of the open Atlantic. If the weather turned bad retreat if possible to the shelter of the Outer Hebrides was the only hope. Even today a boat setting out for St Kilda is by no means assured of reaching its destination.

Next page