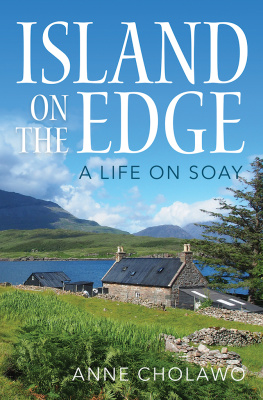

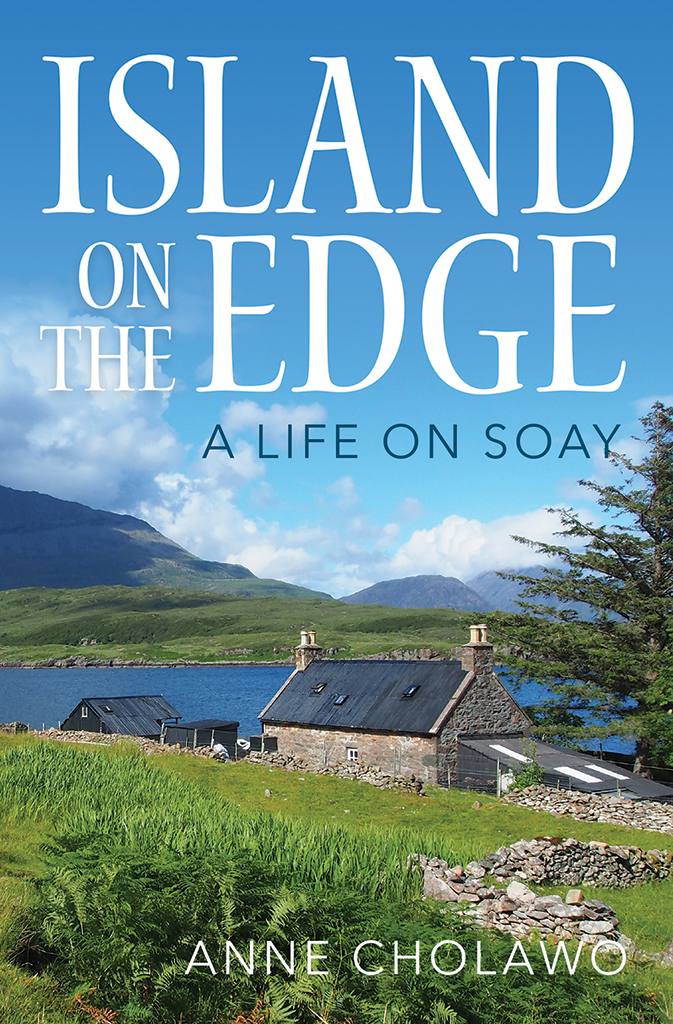

ISLAND ON THE EDGE

First published in 2016 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Anne Cholawo 2016

Part-title illustrations by the author

The moral right of Anne Cholawo to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored or transmitted in any form without the express

written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 349 5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

To Robert

for his support and loving companionship

Dallas Jane Roodhyuzen and David Hollingsworth

for aid, food, clothes, sanctuary and unwavering friendship

Jemma and Luke Cholawo

for being a part of it all

CONTENTS

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

All references to Soays pre-evacuation history taken from The Soay of our Forefathers by Laurance Reed, published by Birlinn Ltd.

Photographs are reproduced by kind consent of Jemma Cholawo, Robert Cholawo and DJ Roodhyuzen. All other illustrations are my own.

I would like to express my wholehearted gratitude to my editor, Fay Young, for her encouragement, hard work and invaluable input. She has helped to bring this book together in a way that I could not have achieved on my own.

Authors note

Since the publication of Harpoon at a Venture by Gavin Maxwell in the early 1950s, the extraordinary human story of those who lived on the Isle of Soay in the years after Maxwells failed shark fishing enterprise has remained untold.

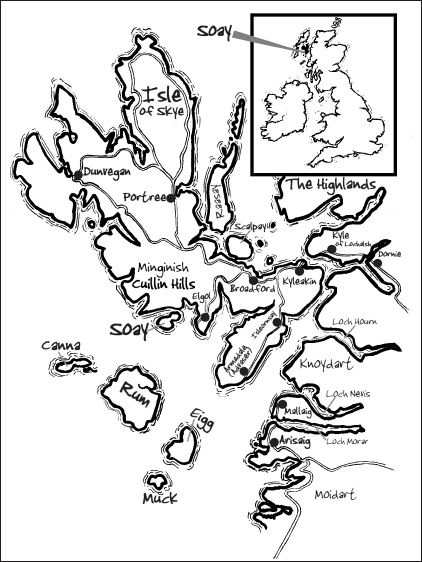

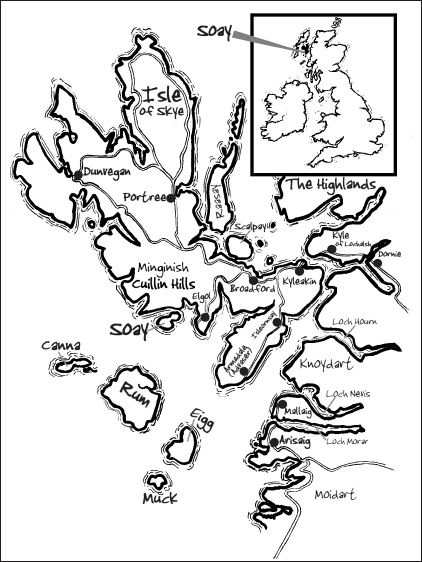

Laurance Reeds invaluable book The Soay of our Forefathers tackles the chronological history of the island from its original ownership by the MacLeods of Dunvegan to the evacuation of the population in 1953. Laurance researched and wrote his book while he was living on the island amongst a newly established post-evacuation population, which was flourishing and relatively stable.

There are surely others who came to live on Soay after the evacuation in 1953 with stories to tell more exciting than mine. However, I do believe that it is important that someone should relate the deeply human aspects of Soays post-evacuation history. The people who were living and working on the island when I first arrived in 1990 were a powerful influence on me and changed my outlook on life forever.

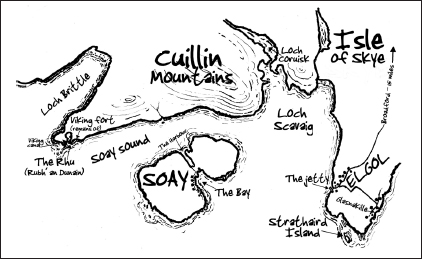

Soay is a very different island to the one that I discovered when I arrived to make a new life here in 1990. In those days there were seventeen inhabitants on the island. I could never have imagined that I would be one of only three full-time residents twenty-six years later. Friends, neighbours and the unforgettable personalities who occupied the houses round the bay are all gone. Yet every time I repair a drystone wall, drill a hole, splice a piece of rope or load another fishbox full of seaweed onto the garden, it reminds me of my former neighbours. Without their help, support, experience and guidance my hopes of a new life would have ended before my first year on Soay was over.

For want of anyone more qualified, I have written about life and events on Soay over the last twenty-six years in the only way I know how: from my own experiences. Some observations will be flawed and possibly on occasion even misconstrued, but they are as accurate as I can make them, allowing certain artistic license for readability purposes. It is my own story.

Anne Cholawo,

Isle of Soay

July 2016

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Access by courtesy of fishing boat

September 1989

Who knows why it caught my eye. On the last day of my holiday on the Isle of Skye I stopped in front of the Portree Estate Agency and there it was. Nothing special. A single colour photograph of Glenfield House showed the front view of a simple, stone-built, one-and-a-half-storey house with a corrugated iron roof. The details were sketchy: just the purchase price and the information that this former croft house was located on the Isle of Soay.

I had never heard of the Isle of Soay. More to the point, I had no idea it was actually an island. This was my first visit to the Hebrides, I knew very little about the Highlands and in my ignorance I confused Soay with Isleornsay, a village at the southern end of Skye. Even so the house captured my imagination. I had only glanced briefly at the picture but the image was burned into my memory. It travelled with me on the five hundred and seventy mile journey home and would not go away. Back in Bedfordshire, I couldnt stop thinking about it. Glenfield House followed me on the daily commute to and from London and it wasnt long before I succumbed to temptation. I contacted the Portree Estate Agency and asked for more details. One evening I came home from my job as a graphic artist in a London advertising agency to find a thin, brown A4 envelope on the doormat. I opened it with barely suppressed excitement and looked more intently at the photograph attached to the propertys details. The envelope contained a single piece of A3 paper folded in two and the description of the house was brief and, for an estate agency, overly honest:

A stone built traditional one-and-a-half-storey croft house with corrugated iron roof. The property comprises of a front entrance hall, a kitchen with a solid fuel Rayburn for cooking and hot water; a two ringed Calor gas cooker and gas fridge. There is a sitting room with a large open fireplace. On the second floor are two main bedrooms plus one small box room/bedroom. There is a large extension to the rear of the building, which consists of a back hall, pantry, bathroom/shower-room and small side room. The property has a moderately sized walled garden area and one drystone outhouse. The property also has a private water supply and cesspit. There is no electricity. Offers over 28,000.

I was confused by the last phrase in the details:

Access by courtesy of fishing boat.

But it merely added to my interest. I didnt have any real understanding of what I might be getting myself into if I took this whim a stage further.

Up to that point, my life had been a mostly urban existence; from my childhood in the industrial sprawl of Luton, to the tiny two-up-one-down cottage that I had been fortunate enough to purchase a few years earlier in the relatively quieter village of Aspley Guise, near Woburn Abbey. So far, I had known nothing but the comforts of modern conveniences and I had never been very far from civilised suburbia. I was well on my way to becoming a real yuppie (young, upwardly propelled person). Maggie Thatchers brave new capitalist England of the 1980s had dominated my young adulthood and made its mark on the way I viewed life. London seemed to me to be the centre of the world.