To my late beloved wife, Joyce R. Tedlow, M.D.

Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.

The problem with the family firm is growth. Either the family grows faster than the firm or the firm grows faster than the family.

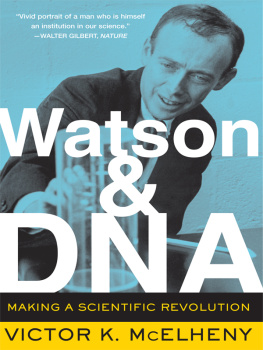

O ne day in April 1993, Lou Gerstner got into his car to drive from his home in Greenwich, Connecticut, to his office in Armonk, New York. On April 1, Gerstner had become the chief executive officer of the International Business Machines Corporation. IBM was on its way to losing $8.1 billion that year, more money than any other business had ever lost.

On this particular morning, Gerstner encountered a little surprise when he opened his car door. He had company. Thomas J. Watson Jr. was already there.

Watson, seventy-nine years old, was a man with a pedigree and a rsum. His father had taken the reins of a small struggling mess of a company in 1914 and turned it into a global powerhouse by the time he retired in 1956. Watson Jr. had taken an already great company and made it greater, introducing one of the most important products in the history of business, the System/360.

But now, Watson was animated, agitated, and angry. He told Gerstner to save my company. He urged bold action.

Many people thought IBMs chances for survival were not good. Many believed that Gerstner was not the man to save it. This book will help explain why the skeptics were wrong. The Watsons had built IBM to last. The process of creating the company took a heavy personal toll on many who were involved. The strength was there, however. The question was: Would Gerstner be able to build on it, or would IBM be sucked into the tar pit of oblivion?

T he worlds fair in New York City at the end of the depression decade was a big deal. Planning began in 1935. The fairgrounds covered 1,216.5 acres in what had been a garbage dump in Queens. By opening day, April 30, 1939, the moonscape that had been Flushing Meadows was transformed, in the perhaps pardonable hyperbole of the guidebook, into a stupendous, gigantic, super-magnificentgreatest show on earth. Time magazine called it the biggest, costliest, most ambitious undertaking ever attempted in the history of international exhibitions.

Over sixty nations had pavilions and exhibits clustered around the Court of Peace on the fairgrounds. Every major country was represented save Germany. New Yorks mayor, Fiorello H. La Guardia, had suggested in 1937 that a Chamber of Horrors be dedicated to Nazi Germany. The Nazis did not see the humor in the idea of the man they labeled a dirty Talmud Jew, lodged a protest with the State Department, and refused to participate in the festivities.

Dozens of corporations saw the fair, with its theme of Building the World of Tomorrow, as an ideal venue for institutional advertising and image making. This fair was to be more than merely a showroom for the display of goods; it was to be, according to historian Roland Marchand, a World Stage upon which to dramatize the advantages of the American system of free enterprise.

Foremost among the more than forty company exhibitors was the nations largest industrial corporation, General Motors. Still smarting from the disastrous sit-down strike in Flint in the winter of 193637, the result of which was the unionization of its plants and the creation of the United Automobile Workers, General Motors was anxious to turn the nations attention to its ambitions for the future. This it attempted to do through Futurama, a remarkable invitation to share our world. It was the hit of the fair, with more attendees and rave reviews than any other exhibit. Other companies spending large amounts of money to educate the public about their greatness included Ford, Chrysler, AT&T, General Electric, and Westinghouse.

Also making their presence known at the fair were the International Business Machines Corporation and its indomitable leader, Thomas J. Watson Sr.

Watson was sixty-five years old when the fair opened, an age when many businessmen think about retirement. But Watson had the energy of a man in his thirties, and we can confidently assert that thoughts of retirement never entered his mind. For years he had been telling his troops, The IBM is not merely an organization of men; it is an institution that will go on forever. He planned to accompany IBM on its journeyif not forever, then at least for a good many more years. And he had every intention of using the fair to tell the world that he and IBMthe two were inseparable in his mindmattered.

On May 2, IBM held a huge meeting at the fair, with 2,200 employees in attendance. Watson told the listening throng that he wanted to keep the business session brief because the fairs educational opportunities are so much broader than anything we could hope to give you that we are going to give you as much time as possible to visit these things. Nevertheless, there were eighteen speakers at the event.

May 2 was as nothing compared to Thursday, May 4IBM Day at the worlds fair. May 4 was a busy day for Watson, but not a uniquely busy day. Indeed, one of the remarkable aspects of his long life was the number of days such as this which he arranged (and which those around him endured). Things were kicked off as Watson opened the fair for the day. He was accompanied by a mounted escort from Perylon Hall on the fairgrounds to the IBM exhibit at the Business Systems Building, where a precursor of a form of E-mail was displayed:

As a demonstration of the latest device out of the I.B.M. research laboratories, a letter of congratulation was flashed through the air from San Francisco to New York on an I.B.M. radio-type. It was offered as the high-speed substitute for mail service in the world of tomorrow.

Not only technology but art had a place in IBM Day. The company had commissioned the IBM Symphony by Vittorio Giannini, and the work was performed at this event and was broadcast. In a burst of understatement, Fortune magazine described the symphony as somewhat programmatic in nature. The second movement contained a melodic reference to the most often sung of IBMs many songs, Ever Onward.

Painting as well as music was part of IBMs artistic contribution to the fair. Watson was described in the New York Times as taking a bold and potentially constructive step by displaying works from seventy-nine countries in his Gallery of Science and Art in a large hall in the Business Systems Building at the fair. Far-flung would be the best way to describe the countries represented. They included French Indochina, Libya, Luxembourg, and the USSR. Our endeavor, explained Watson,

has been to increase the interest of business in art and of artists in business. This step by an industrial organization is in recognition of the part played by art in industry and its importance to industry in broadening the horizons of culture and influencing the needs and desires of the people of every country.

Whatever that might mean.

This collection traveled from one country to another after the fair. To be sure, sniffed the Times reporter, representation by one painter alone [from each country] is inclined to provoke a smile and must have caused prodigious head-scratching. Nevertheless, the plan was pronounced to [work] well enoughupon the whole. This project generated a good deal of publicity for Watson and for IBM.

Watson made speeches during IBM Day (As a businessman, I think of world peace as a sales problemwhat intelligent response, one wonders, could be made to such an assertion?), received compliments, and unveiled a statue of Peter Stuyvesant, the last colonial Dutch governor of what was New Amsterdam and became New York, at the Dutch pavilion.