RICHARD S. TEDLOW

Joyce R. Tedlow, M.D.

In compiling a list of people who helped me in the course of writing this book, I am quite struck by how many to whom I owe gratitude. It has been my great good fortune to have as friends and colleagues so many who supported this project.

Helen Rees, my agent, first showed confidence in this book, and her advice from start to finish has been indispensable. She put me in touch with Adrian Zackheim, senior vice president and associate publisher at HarperBusiness, and we struck a deal with Helens assistance over the phone in a matter of about a minute. Adrian and his team, including Joe Veltre, have had a deep understanding of what I have tried to do with Giants of Enterprise.

I had been thinking about this book for many years, but the actual writing began about the time that Kim B. Clark became dean of the Harvard Business School in 1995. Much of the collegiality from which I benefited was the result of his goals and aspirations for the school. Giants was funded by the Division of Research, where Ken Froot, year after year, was unfailingly generous. Each chapter of this book has been presented at a seminar at the school, and many improvements have resulted. I received advice and ideas from many members of the faculty. These include Carliss Baldwin, Adam Brandenburger, Al Chandler, John Deighton, Bob Dolan, Susan Fournier, Linda Hill, Geoff Jones, Bob Kennedy, Rakesh Khurana, Nancy Koehn, Anita McGahan, Huw Pill, Forest Reinhardt, Mike Roberts, Dick Rosenbloom, Julio Rotemberg, Bill Sahlman, Walt Salmon, Debora Spar, Don Sull, Dick Vietor, Jonathan West, David Yoffie, and Abe Zaleznik. A special note of thanks is due to Tom McCraw, the leader of the business history enterprise at the Harvard Business School.

On the schools staff, I would like to express my gratitude to Chris Albanese, Chris Allen, Kim Bettcher, Jeff Cronin, Chris Darwall, Sarah Eriksen, Walter Friedman, Courtney Purrington, Kathleen Ryan, and Margaret Willard.

Many scholars, businesspeople, and personal friends lent a welcome helping hand. These include Jim Amoss, Ann Bowers, Kathy Connor, Lillian Cravotta-Crouch, Bob Cuff, Bill Donaldson, Lynn Groff, Andy Grove, Reed Hundt, Richard John, Analisa Lattes, Erik Lund, Sandy Lynch, Darlene Mann, Susan McCraw, Gordon Moore, Pendred Noyce, M.D., Rowena Olegario, Cliff Reid, Martin Revson, Barbara Rifkind, Arthur Rock, Linda Smith, Charles Spencer, Irwin Tomash, and Les Vadasz.

My greatest debt of gratitude is owed to my wife, Joyce. A psychiatrist, Joyce supplied intellectual insight concerning the subjects of this book and a great deal of emotional support to its author. She did this in the midst of a challenging situation with regard to her health. She never lost faith.

This is a book about what Americans do bestfounding and building new businesses. It is about men who broke old rules and made new ones, who built new worlds, who were determined to govern and not to be governed,1 who exploited tools and techniques of which their contemporaries were only vaguely aware to serve markets which in some instances they had to create. The seven men portrayed in these pages were individuals of extraordinary inner drive and competitiveness living in a country and culture which encouraged those traits and channeled them into business enterprise. Each in his own way was an outstanding person, living in a nation which allowed him to give full vent to his talent. These men in this country were as free as anyone can be in this world.

Had these seven men been Italians, perhaps they would have become composers; and the world would have seen a second Verdi rather than mass-marketed photography. He wept for us; he loved for us, was DAnnunzios farewell to Verdi in his memorial.2 Had they been Russians, perhaps they would have been novelists. On September 27, 1867, when he was in the midst of the Great Labor which became War and Peace , Tolstoy wrote his wife: God grant me health and peace and quiet, and I shall describe the battle of Borodino as it has never been described before.3 Had they been Portuguese, perhaps they would have been navigators; Germans, soldiers; Japanese, servants of the state; Romanians, gymnasts. And so forth.

America has produced people able to do all these things (just as these nations have all produced businesspeople); but, speaking generally, America as a nation and a culture has not distinguished itself as the best in any of them. Isolated instances of excellence spring up in a variety of endeavors all over the world, sometimes in pretty unexpected places. When one takes the long view, howeversay, 250 yearsit is fair to assert that America has been the best in starting and nurturing companies. This, therefore, is a book about the best of the best.

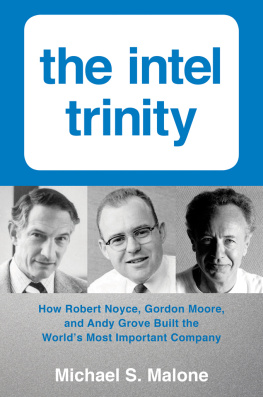

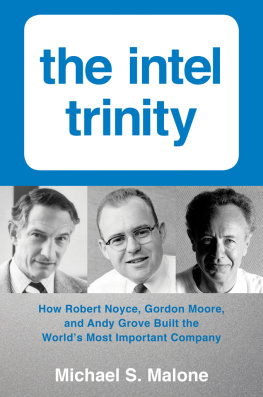

Why these seven? The most important reason is that their lives and careers span a lengthy period of time. Andrew Carnegie was born in 1835. He became a force in the business world in the 1860s. The last two biographies are of Sam Walton and Robert Noyce, both of whom died in the 1990s. So their careers provide the opportunity to see how founding and building companies in the United States changed over time.

The seven biographical essays in this book are divided into three sets. The first setCarnegie, Eastman, and Fordillustrates the transition from the United States as a developing country to world leadership. The secondWatson and Revsonillustrates leadership in an industrial marketer (IBM) and a consumer marketer (Revlon) during the middle decades of the twentieth century. The thirdWalton and Noyceprovides the same contrast between a consumer business (Wal-Mart) and an industrial business (Intel) toward the end of the century. They also show different leadership styles in the oldest of industries (retailing) and the newest (semiconductor electronics). These seven portraits will enable us to explore in the concluding chapter the fundamental changes in the demands on business leaders from the Civil War to 1990.

Another selection criterion was regional. Business leaders act differently in different parts of the United States. Andrew Carnegie was born near Edinburgh, Scotland, and made his fortune in Pittsburgh. George Eastman was born in upper New York State and established Kodaks headquarters in Rochester. Ford was born and spent his working life in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn. Watson, like Eastman, was born in upper New York State and spent his working life in New York City. Revson was born in Boston and, like Watson, established his firms headquarters in New York City. Walton was born in Kingfisher, Oklahoma. Wal-Marts headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas, gives us a glimpse of business south of the Mason-Dixon line. Noyce was born in Denmark, Iowa, and established Intel in Santa Clara, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley.