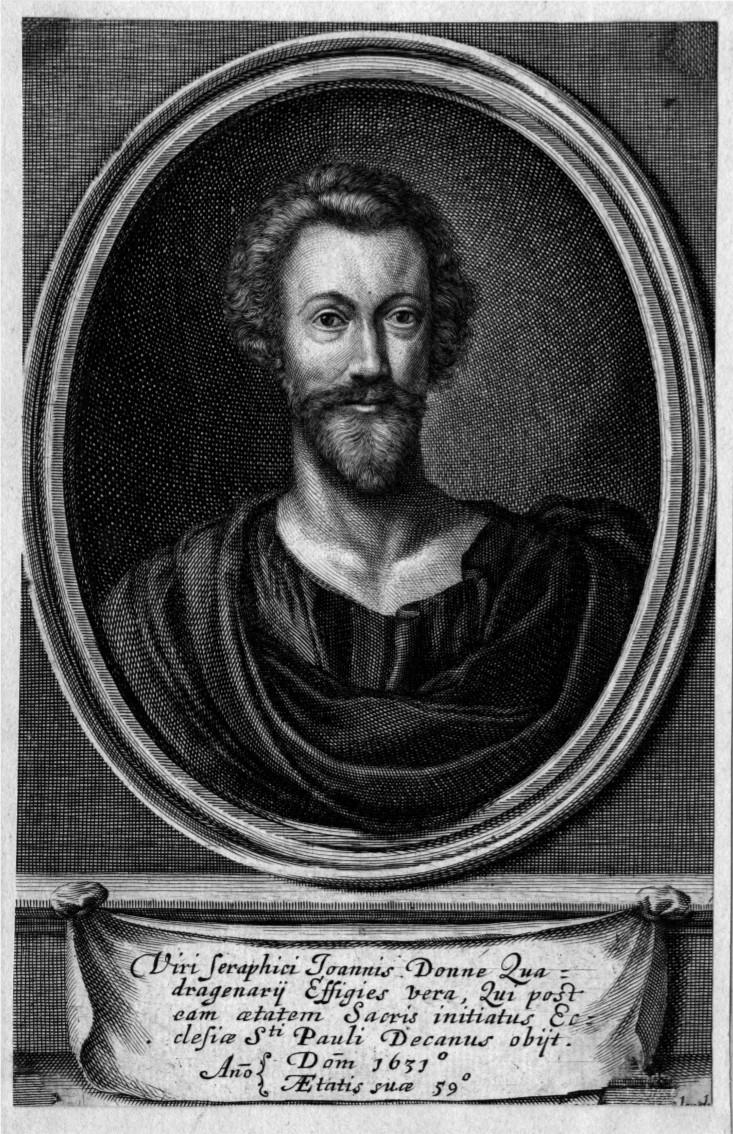

The power of John Donnes words nearly killed a man. It was the late spring of 1623, on the morning of Ascension Day, and Donne had finally secured for himself celebrity, fortune and a captive audience. He had been appointed the Dean of St Pauls Cathedral two years before: he was fifty-one, slim and amply bearded, and his preaching was famous across the whole of London. His congregation merchants, aristocrats, actors in elaborate ruffs, the whole sweep of the city came to his sermons carrying paper and ink,

That morning he was not preaching in his own church, but fifteen minutes easy walk across London at Lincolns Inn, where a new chapel was being consecrated. Word went out: wherever he was, people came flocking, often in their thousands, to hear him speak. That morning, too many people flocked. There was a great concourse of noblemen and gentlemen, and in among the extreme press and thronging, as they pushed closer to hear his words, men in the crowd were shoved to the ground and trampled. Two or three were endangered, and taken up dead for the time. Theres no record of Donne halting his sermon; so its likely that he kept going in his rich, authoritative voice as the bruised men were carried off and out of sight.

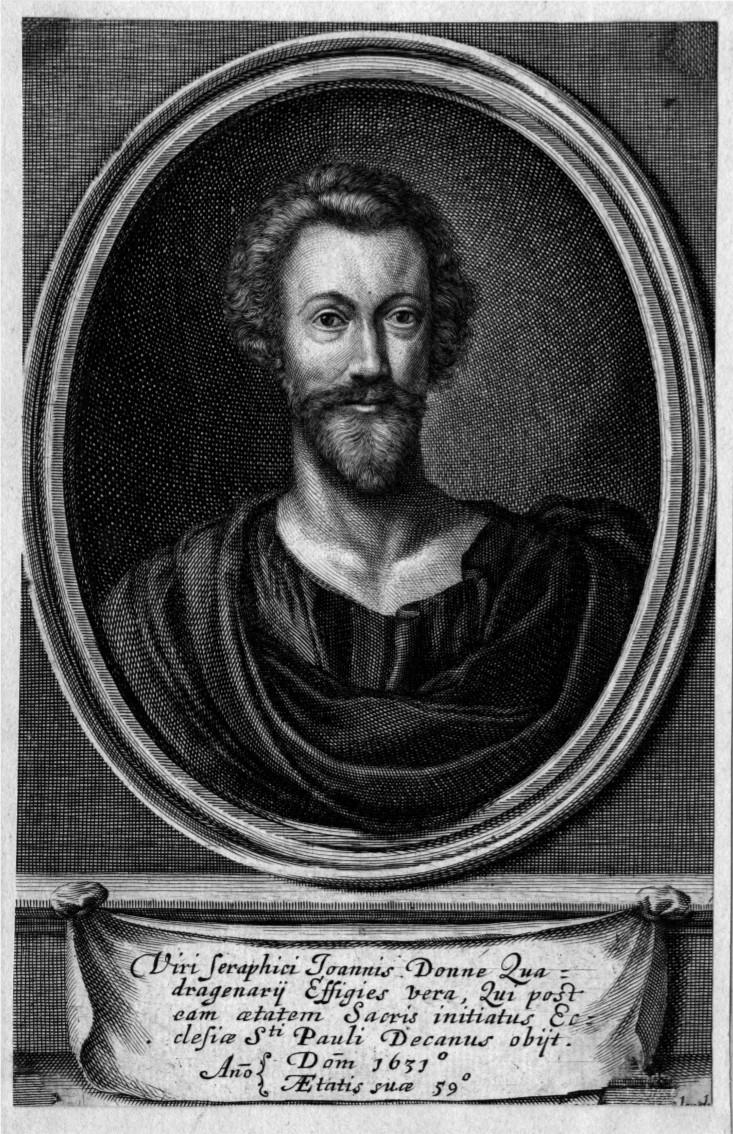

Donne the preacher: engraving by Pierre Lombart, after an unknown painting

II

Just fifteen years before that, the same man finished a book and immediately put it away. He knew as he wrote it that it could be dangerous to him were it to be discovered. He was living in obscurity in Mitcham, in a cold house with thin walls and a noxious cellar that leaked raw vapours to the rooms above, distracted by a handful of gamesome and clamouring children. It was a book written in illness and poverty, to be read by almost no one. The book was called Biathanatos; a text which has claim to being the first full-length treatise on suicide written in English. It laid out, with painstaking precision, how often its author dreamed of killing himself.

III

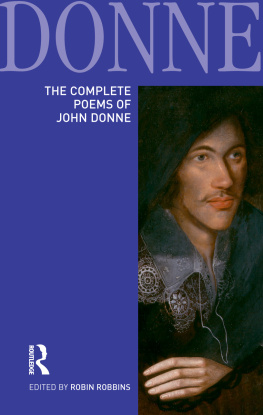

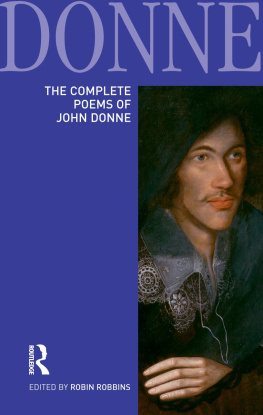

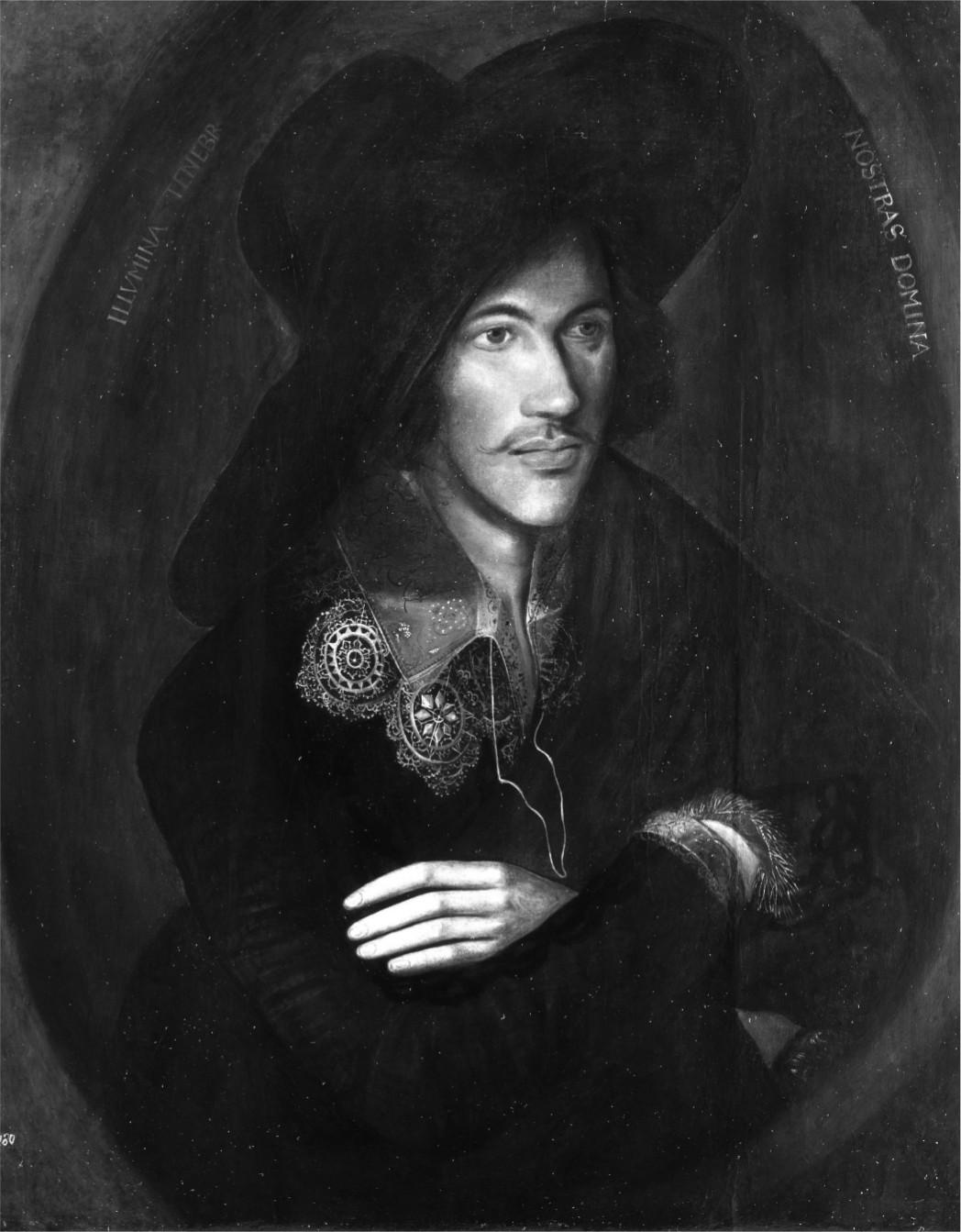

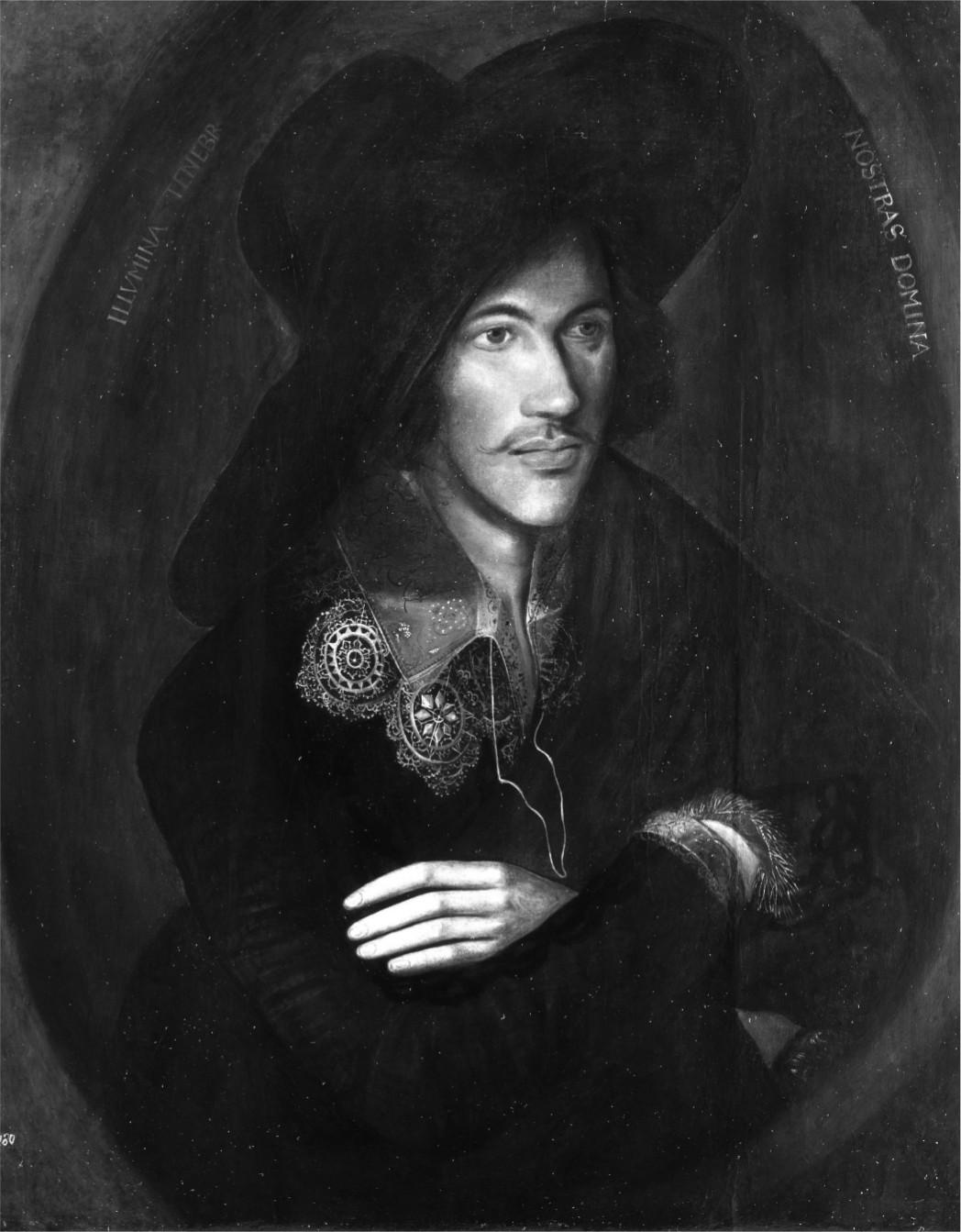

A decade or so before, the same man, then about twenty-three years old, sat for a portrait. The painting was of a man who knew about fashion; he wore a hat big enough to sail a cat in, a big lace collar, an exquisite moustache. He positioned the pommel of his sword to be just visible, an accessory more than a weapon. Around the edge of the canvas was painted in Latin, O Lady, lighten our darkness; a not-quite-blasphemous misquotation of Psalm 17, his prayer addressed not to God but to a lover. And his beauty deserved walk-on music, rock-and-roll lute: all architectural jawline and hooked eyebrows. Those eyebrows were the author of some of the most celebratory and most lavishly sexed poetry ever written in English, shared among an intimate and loyal group of hyper-educated friends:

License my roving hands, and let them go

Behind, before, above, between, below!

O my America! My new-found land!

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man manned!

The Lothian Portrait, artist unknown, c.1595

Sometime religious outsider and social disaster, sometime celebrity preacher and establishment darling, John Donne was incapable of being just one thing. He reimagined and reinvented himself, over and over: he was a poet, lover, essayist, lawyer, pirate, recusant, preacher, satirist, politician, courtier, chaplain to the King, dean of the finest cathedral in London. Its traditional to imagine two Donnes Jack Donne, the youthful rake, and Dr Donne, the older, wiser priest, a split Donne himself imagined in a letter to a friend but he was infinitely more various and unpredictable than that.

Donne loved the trans- prefix: its scattered everywhere across his writing transpose, translate, transport, transubstantiate. In this Latin preposition across, to the other side of, over, beyond he saw both the chaos and potential of us. We are, he believed, creatures born transformable. He knew of transformation into misery: But O, self-traitor, but transubstantiates you.

And then there was the transformation of himself: from failure and penury, to recognition within his lifetime as one of the finest minds of his age; one whose work, if allowed under your skin, can offer joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you. Because amid all Donnes reinventions, there was a constant running through his life and work: he remained steadfast in his belief that we, humans, are at once a catastrophe and a miracle.

There are few writers of his time who faced greater horror. Donnes family history was one of blood and fire; a great-uncle was arrested in an anti-Catholic raid and executed: another was locked inside the Tower of London, where as a small schoolboy Donne visited him, venturing fearfully in among the men convicted to death. As a student, a young priest whom his brother had tried to shelter was captured, hanged, drawn and quartered. His brother was taken by the priest hunters at the same time, tortured and locked in a plague-ridden jail. At sea, Donne watched in horror and fascination as dozens of sailors burned to death. He married a young woman, Anne More, clandestine and hurried by love, and as a result found himself thrown in prison, spending dismayed ice-cold winter months first in a disease-ridden cell and then under house arrest. Once married, they were often poor, and at the mercy of richer friends and relations; he knew what it was to be jealous and thwarted and bitter. He was racked, over and over again, by life-threatening illnesses, with dozens of bouts of fever, aching throat, vomiting; at least three times it was believed he was dying. He lost, over the course of his life, six children: Francis at seven, Lucy at nineteen, Mary at three, an unnamed stillborn baby, Nicholas as an infant, another stillborn child. He lost Anne, at the age of thirty-three, her body destroyed by bearing twelve children. He thought often of sin, and miserable failure, and suicide. He believed us unique in our capacity to ruin ourselves: Nothing but man, of all envenomed things,/Doth work upon itself with inborn sting. He was a man who walked so often in darkness that it became for him a daily commute.